6. Summary of consultation responses

The Equality Commission states that consultation should be inclusive, afford a fair opportunity to communicate pertinent information and enable consultees to give advice and opinion on the policy so that the public authority may reach a more informed decision. The Equality Commission has also made it clear that an EQIA should not be considered as a referendum whereby the views of consultees from a majority are counted as votes to decide the outcome.Footnote eight

The consultation process on this EQIA covered a 14-week period from 10 August to 20 November 2022. During the consultation period, the draft EQIA report was available on Belfast City Council’s Your Say consultation website. It was accompanied by a survey inviting feedback on the Belfast Stories proposal and draft EQIA. The council’s Equality Scheme consultees were notified of the draft EQIA and invited to comment. Leaflets and information were distributed across the city and a series of meetings, workshops and events were held.Footnote nine

Responses were received as follows.

Survey responses in relation to the draft EQIA

One hundred and twenty-seven people responded to the survey on Belfast City Council’s Your Say Belfast consultation website.Footnote ten Of those, 50 people (39.4 per cent) answered questions specifically on the draft EQIA.

Demographic breakdown of respondents

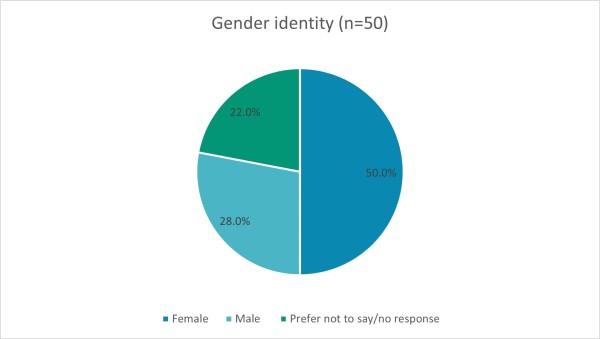

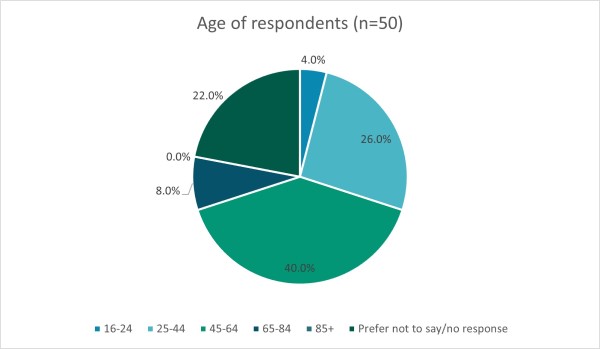

The majority of respondents were female (50.0 per cent) and aged between 16 and 64 (66.0 per cent).

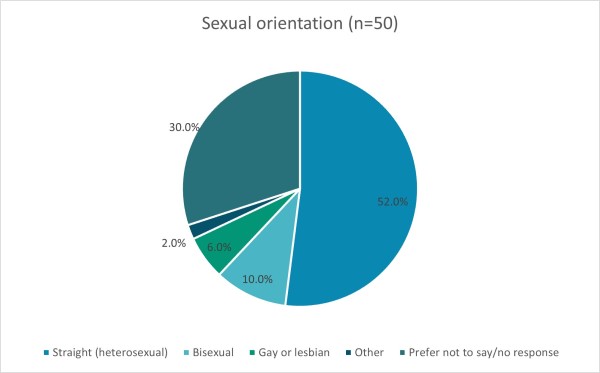

52.0 per cent of respondents identified as straight, and 18.0 per cent identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual or other.

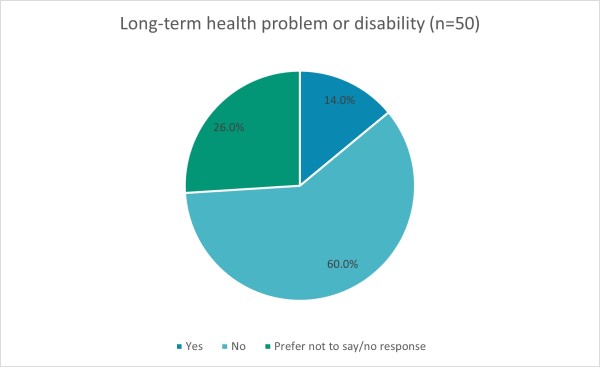

14 per cent identified as being disabled or having a long-term health problem that limits their day-to-day activity.

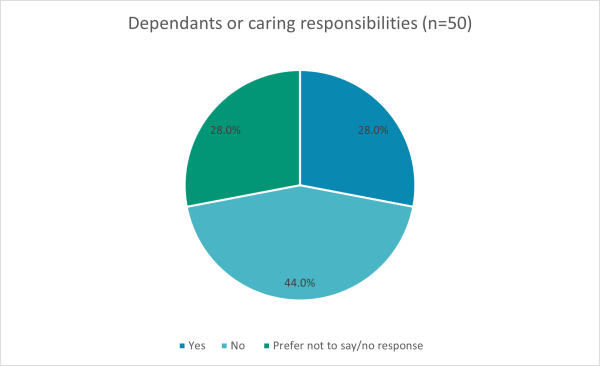

28.0 per cent had dependents or caring responsibilities for family members or other persons.

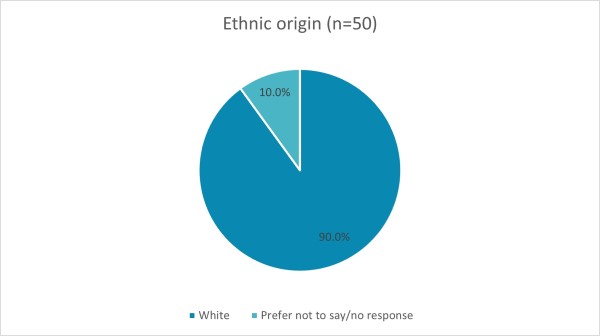

90 per cent identified as being from a white community background.

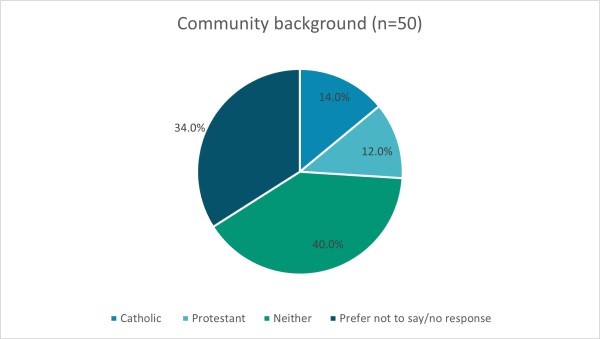

14.0 per cent identified as being from a Catholic community background; 12.0 per cent from a Protestant community background; and 40.0 per cent from neither a Catholic nor Protestant community background.

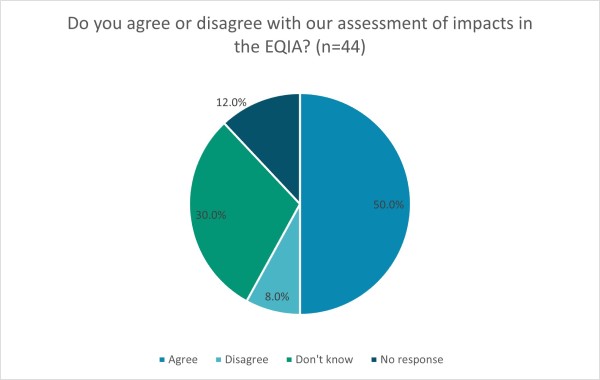

Agreement with the assessment of impacts

The majority of respondents agreed with the assessment of impacts. 8 per cent disagreed.

Reasons given by those who disagreed with the assessment of impacts were:

- “not all sides get listened to.”

- “Let’s break down the various communities and see what might appeal to the public at large. Taxpayers that vote in the council and pay for it. The project must cater to those that have shaped Belfast”

- “I have not read into the policy and data to make my own mind up on this question. Further open access research needs to be available and open to public.”

Additional impacts

There were 17 responses to the question “Are you aware of any other impacts that we haven't identified?” including 11 responses (64.7 per cent) stating that they could not identify additional impacts.

One response reinforced the opportunity to improve good relations. Other responses were less relevant to good relations or equality of opportunity across Section 75 protected characteristics.Footnote eleven

Additional evidence

There were 14 responses to the question “Are you aware of any other evidence or research that may be relevant to Belfast Stories impact assessment?”. Of these, 11 (78.6 per cent) were unaware of additional evidence. Other responses were:

- “Do not have the time to study in depth.”

- “Research can be biased based on who carried it out, what was the remit and the reason for it.”

- “Boston College revelations of interviewees' data.”

Opportunities to promote equality of opportunity and Good Relations

There were 25 responses to the question “What else could we do to promote equality of opportunity and good relations?”. Accordingly:

- 7 responses emphasised the importance of consultation and engagement, and 4 listed additional groups they felt should be engaged. There were homeless people, care homes, “advocacy agencies” and primary schools.

- 2 respondents emphasised the need for ongoing monitoring and evaluation, although another respondent felt that there should be “Less tick boxing. It needs to develop on an individual basis – rather than representatively.”

- 2 responses felt that Belfast Stories should be wider than Belfast

- Suggestions to promote good relations included ensuring there is political balance; using arts and festivals to promote good relations; and challenging the received narratives (“Ensure there is a focus on unifying stories – Belfast hasn't always been a divided city – lets hear about that! What was it like post troubles? When we all lived as one and no one cared about your religious background. I appreciate we need to speak of the troubles but this should by no means be the overall story of this place.

- We are much more than that.”; “make sure not to work in a way that allows gatekeepers”).

Responses to the overall survey

One hundred and 27 responses were received across the whole survey which, in addition to the questions specific to the draft EQIA, asked:

- What might stop you from enjoying Belfast Stories?

- Have we identified the right people for the equity steering group?

- Are there any other groups of people at risk of missing out?

- How else can we engage with people at risk of missing out?

- Is the story collection framework a good foundation for gathering stories?

- What might stop you telling your story?

- What support might people in your community or organisation need to share their stories?

Demographic breakdown of responses across the overall survey

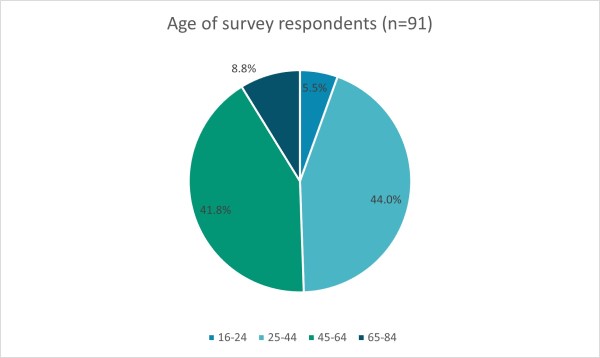

85.8 per cent of respondents were aged 25 to 64.

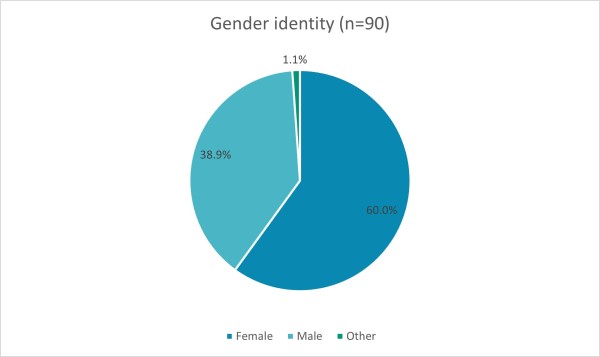

60.0 per cent of respondents were female and 38.9 per cent male.

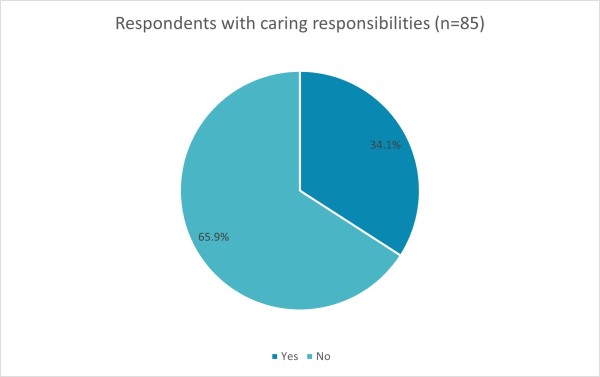

34.1 per cent of respondents have caring responsibilities including 20 per cent with responsibility for caring for an older person or disabled person.

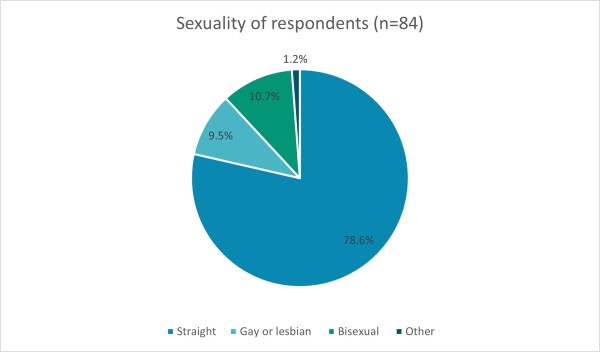

78.6 per cent of respondents identified as straight (heterosexual) and 21.4 per cent identified as gay, lesbian, bisexual or other (“queer”).

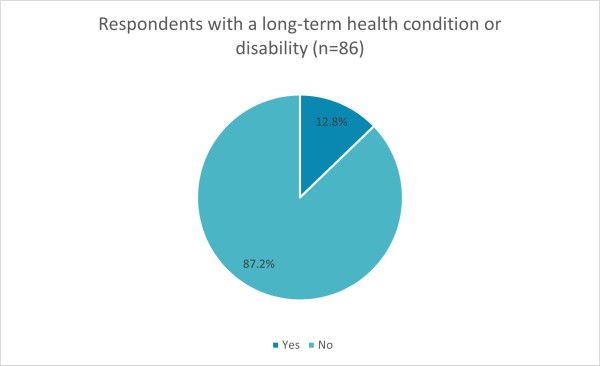

12.8 per cent of respondents indicated that they had a long-term health condition or disability that limits their day-to-day activity.

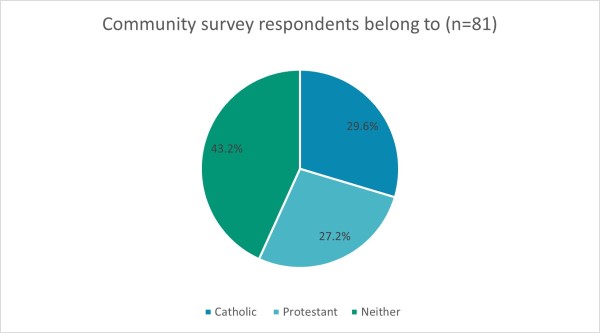

29.6 per cent of survey respondents identified as belonging to the Catholic community; 27.2 per cent identified as from the Protestant community; and 43.2 per cent identified as belonging to neither community.

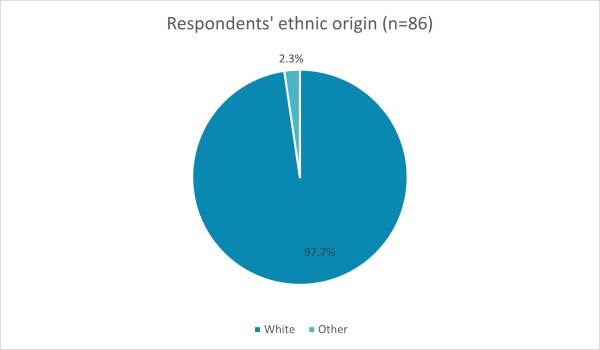

97.7 per cent of respondents identified as white, and 2.3 per cent identified as other including from a mixed ethnic background.

Equity steering group

In August 2022, an equity steering group was set up comprising 10 experts by experience including people from Black, Asian, Middle Eastern, inner city, working class and LGBTQ+ backgrounds; older and younger people; disabled and neurodiverse people; and people with caring responsibilities.

There were four equity steering group meetings during the public consultation, which were attended by an average of eight people (31 in total).

Other engagement around equality, diversity and inclusion

A further 16 workshops were facilitated with people and groups who are generally less heard or more at risk of missing out. These were attended by 136 people (9 on average).

Ten one-to-one meetings were also held with organisations representing or advocating for people and groups at risk of missing out.

Engagement with sectoral stakeholders

There were 31 workshops with the film, tourism, arts, heritage, the voluntary and community, Irish language and public sectors, engaging 238 representatives.

Written submissions were also received from seven organisations (see appendix 7).

Engagement with the general public

Belfast City Council facilitated four public meetings. These took place in the north, south, east and west of the city and were attended by 15 participants.

Information boards were displayed at Clifton House, Girdwood Community Hub, Lisnasharragh Leisure Centre, Crescent Arts Centre, Ulster University, Spectrum Centre, EastSide Visitor Centre and the James Connolly Visitor Centre.

In August 2022, Belfast City Council appointed thrive, the audience development agency for NI, and Daisy Chain Inc, a creative consultancy, to help raise awareness and build excitement including through on-street interviews, events and workshops and pop-up consultation hubs in central and surrounding locations. They engaged a total of 683 participants.

Relevant findings from wider engagement

Building the excitement

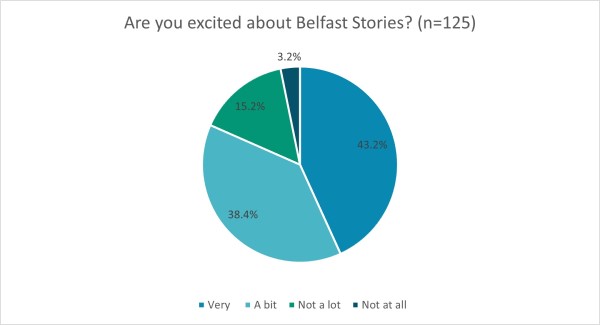

Across all engagement strands, there was remarkable excitement about the concept of Belfast Stories. For example, in survey responses, 81.6 per cent of survey respondents said they were excited about Belfast Stories, with 43.2 per cent saying they felt “very” excited.

Reasons people felt excited included:

- looking forward to the regeneration of the area, which many felt was run down, unwelcoming or even unsafe (“the area is a mess a disgrace so it will be a shot in the arm for the area”)

- recognition of an opportunity to change the usual negative, narrow or “us and them” narrative of Belfast. (“Think it's a great opportunity to tell stories of the city and its people that transcend tired and unrepresentative binary views.”)

- a potential boost to pride at both civic and individual level.

“So important to capture the stories of our city by the people who make it, particularly those of senior citizens whose views are often seen as irrelevant.”

“The idea excites us, the Roma have never been included in anything like this”

Among participants who were unsure about the concept, concerns included:

- Not knowing enough about it. Some struggled with being consulted on a concept, rather than on set plans or physical designs.

- Timescales. As the building is not due to open until 2028, some felt that it was too far in the future to be of interest.

- There was suspicion about the political narrative, specifically that the centre would “just” tell the usual “us and them” narrative or, for some people, concerns that it would just tell the story of “them”.

- There were also concerns about authenticity, which qualified a lot of opinions, including those who were otherwise excited for Belfast Stories. For example, “I am excited if it is not watered down” or “Disney-ified” or is if it is “true to me”.

Among those who were not excited or disagreed strongly with the concept, the main concern was that the investment would be better spent elsewhere or is diverting funding from other priorities, such as preserving other heritage buildings or investment in existing arts and cultural infrastructure.

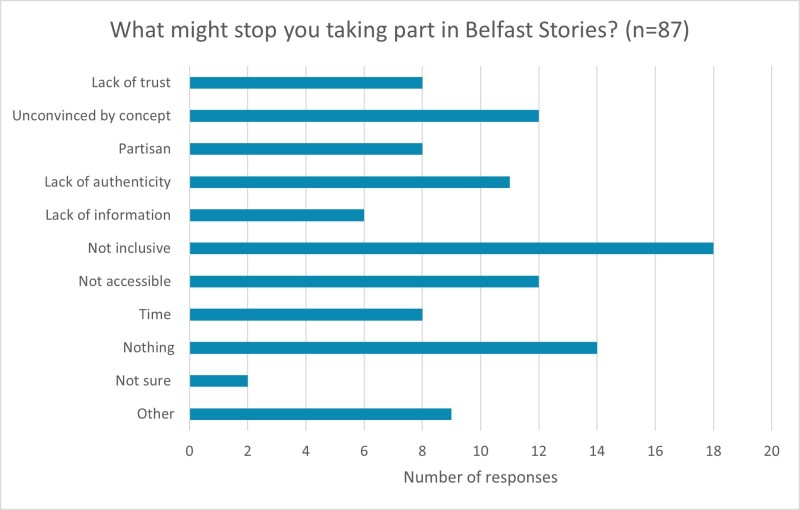

Barriers that would stop people enjoying Belfast Stories

The survey asked, “What might stop you taking part in Belfast Stories?”. Eighty-seven responses were received. Most related to the participating in the story collection process, rather than visiting the physical building.

Eighteen responses related to a perceived or potential lack of inclusivity. This included people who felt that their culture would not be welcome (“one sided narratives”, “if it is classist or erases minorities”, “because I know my faith and culture is not wanted”) and people living outside Belfast (26 per cent of respondents (24 people) were from outside Belfast), who were unsure whether they were included in Belfast Stories.

However, among the 12 responses that were unconvinced by the concept of Belfast Stories, there were concerns that there is too much emphasis on equality or particular equality groups:

- “Woke-ism gone mad.”

- “If I felt like the focus was so far onto marginalised groups that ordinary, educated, white middle-class people aren't encouraged to also apply and feel like we have a chance too.”

Eight responses also indicated concern that the content would be politically partisan.

Twelve responses related to access including the location of the building (getting there and perceptions of safety), cost and lack of adjustments.

The building

Across all engagement strands, barriers identified that would stop people accessing the building included:

- Cost. It was felt that at least some of Belfast Stories (such as social spaces, retail, restaurants and bars) should be free to enter and that different pricing models for locals and tourists should be explored.

- “Not for the likes of us”. Some consultees felt that the building might not be welcoming, at least to “the likes of” them. Consultees reinforced the importance of staff training and skills to create a warm welcome.

- Lack of activity for children. Consultees wanted family-friendly activity and a play area.

- Young people not welcome. It was felt that there is a lack of space in Belfast where young people can just “hang out” safely, particularly away from alcohol.

- Whole family appeal. Consultees indicated a lack of activities in Belfast that would appeal to different generations, from toddlers to grandparents.

- Safety and fear of anti-social behaviour. This was a greater issue for older people and disabled people, particularly when combined with lack of transport which increases the risk of people being left alone and at night. People from minoritised ethnic communities and the LGBTQ+ community also described being subject to racist and homophobic abuse (for example, “The current approach along Royal Avenue involves being shouted at by preachers declaiming the LGBTQIA+.”).

- Transport. This was a major concern, particularly among older people, disabled people, minoritised ethnic communities, carers and people living in working class areas. Concerns included lack of parking spaces and accessible parking and cost of parking. There was also felt to be poor public transport links and a scarcity of taxis, both of which are worse at night, further hindering the evening economy. Consultees would welcome a free shuttle bus down Royal Avenue and better transport links, particularly at night and to rural areas.

- Building design. This was of particular concern to older people, neurodiverse people and disabled people. It was also recognised that inclusive design would benefit the rest of the population, in particular children and parents. The new wing of the Ulster Hospital was cited as an example of good, inclusive design. Other ideas included:

- Architects, designers, restaurant tenants, Belfast Stories staff and so on all to benefit from dementia-friendly training

- Carers, people with dementia and older people to work with the building design team

- Colour-coded floors

- Laminate floor should run length of grain (otherwise creates perception barriers)

- Clear signage

- Way out signs inside toilets

- Quiet areas throughout the building (not just one for whole attraction or exhibition, but in the lobby, restaurants and social spaces as well)

- Red and blue plates for people with dementia so they can see pale food

- Assisted or lightweight doors

- No or dropped kerbs and level access from parking areas and in to the building

- Access for mobility scooters

- Plenty of toilets including changing places

- Accessible toilets (not “disabled” toilets)

- Gender neutral facilities and spaces

- Plenty of seating

- Wide lifts

- Firefighting or evacuation lifts

- Good lighting

- Good acoustics

- Soft surfaces to absorb sound

- Vertigo warnings on the roof garden and viewing platform

- Unilingual signage. This was felt to be a particular barrier for the Irish language community.

For carers and disabled people, a good practice buddy ticketing system was essential. It was also felt that older people may need more encouragement to go out after the pandemic and that the centre should facilitate group visits.

The exhibition

Barriers identified across all engagement strands that might stop people enjoying the exhibition included:

- Cost. This was the main issue raised in relation to the exhibition for local people.

- Lack of interest or relevance. This barrier was identified most frequently in the survey. As ensuring relevance was the part of the main purpose for many workshops, this barrier came up less frequently in person. Suggestions to help mitigate these barriers included engagement with minoritised groups and combining visual and audio archive footage with first-person stories for older people and people with dementia.

- Different language and literacy abilities (such as children and newcomer, Roma and d/Deaf communities). Generally, people preferred the exhibition to be “not too wordy”, favouring “more powerful” visuals. A mix of media was also felt to better “help get someone’s identity”. Suggestions included changing colours, lighting or music to reflect the stories or how people are supposed to feel in response.

- Triggering content, including “Dark stories” that could traumatise or retraumatise, flashing images and loud noises

- Lack of outreach. This would extend the engagement approach after the building has opened to ensure people and groups more at risk of missing out have the opportunity to take part.

- Marketing that is not inclusive of diverse communities (“Not just white princesses from Frozen”)

Suggestions to help mitigate these barriers included:

- Simultaneous translation

- Phone or digital apps to engage with the exhibition in own language

- Interactive activities, games and augmented reality

- Programmable community performance space

- Programmable community exhibition space

- Community spaces (for example, for a monthly d/Deaf community meet-up)

- A changing programme marking civic or cultural events (such as Christmas and Chinese New Year)

- Parental guidance-type warnings

- Quiet spaces

- Use of images showing diverse communities (including but not limited to LGBTQ+ people and people from minoritised ethnic communities)

- English and Irish signage, exhibition text, marketing and other materials

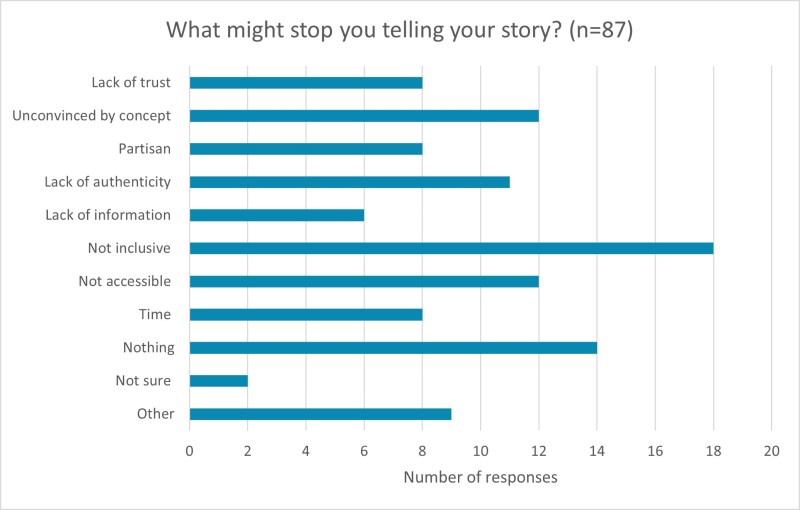

Barriers that would stop people telling their stories

The survey asked, “What might stop you telling your story?”. Responses broadly mirrored the responses to the “What would stop you taking part in Belfast Stories?” question. In practice, during workshops and other in-person engagement, the vast majority of people were very willing to tell their stories.

Some people indicated that they would be more comfortable telling their story to another person. This would be more conversational, prompting them to open up or dive deeper. It would also help overcome barriers around literacy and language abilities, from dyslexia, other first languages or simply embarrassment at poor spelling.

Others would prefer to write or record their story direct, whether finding this approach more creative or less exposing.

During in-person consultation, only a very few felt that they had no story to tell (“Who would be interested in my story?”; “Other people have told stories better”). Generally, young women appeared more reticent than young men, and women more reticent than men in general. Young people were also very concerned with their public profile and would only tell their story (in 2028) “if they were successful”.

Group dynamics helped people overcome initial reticence. For example, at the carers workshop, those who felt their stories were not interesting enough were chivvied along by peers who championed carers as “unsung heroes” who are “not recognised enough”. They were quickly boosted, and stories were shared.

In other group settings where it might be perceived that they could be a lack of trust, for example, with minoritised ethnic groups, they were again happy to open up within their peer group. It may be less likely that they would have told their stories individually.

Still, others may prefer the privacy of individual story collection, particularly those who have sensitive or traumatic stories to tell. There was concern about the potential for storytelling to retraumatise. Organisations such as the Victims and Survivors Service have excellent, tried-and-tested policies and practices co-designed with the intended beneficiaries.

Another barrier that emerged through in-person engagement is storytelling fatigue. This may particularly affect people whose stories are of academic interest; victims, survivors, older LGBTQ+ people (particularly men), ex-combatants and -prisoners, for example, may already have told their stories, sometimes more than once, to researchers.

Many people’s stories have also already been collected through community groups, reminiscence projects, local history associations and so on. In general, participants indicated they would prefer that this activity is shared or showcased, rather than stories recorded anew.

This also points again to the need for a foundation of trust. While the majority of participants in the consultation had little reticence sharing their stories with the facilitators, who were generally unknown to the participants, many of the workshops were organised or supported by trusted intermediaries, whether a local community group or respected individual “of” that community, which helped reassure participants.

One person felt that people collecting the stories should be local people. Another felt that collectors should be “of” the community stories are being collected from (so, for example, someone with Irish language should collect stories from the Irish language community). Another felt that the stories should be interpreted by Belfast people. Overall, “It shouldn’t be two white men”.

The use of trusted intermediaries is likely to be particularly important for vulnerable or marginalized groups. Consultees suggested that where stories had not already been collected, tools that could be used included training and resourcing (for example, with interview scripts, facilitators, digital recording devices and so on) community groups to collect stories, training peer facilitators and using arts to help people open up and approach stories more obliquely.

Some would be happy to have their words used, but not their voice (because they dislike the sound of their voice on recordings); others would be happy to have their voice used, but not their face. Several consultees, particularly among minoritised ethnic groups and young people, wondered whether they could use an avatar instead.

There was concern that the collection process could be difficult or cumbersome, particularly for those with different literacy or memory loss.

Other suggested tools and techniques that might help different people and groups share their story include:

- “story stations” or booths distributed throughout the city

- storytelling hubs in libraries

- storytelling booths in Belfast Stories (including onsite during the build)

- provision of example stories

- reminiscence workshops (“Best asset is the film archive – use this to generate stories; let people remember, then tell stories.”)

- walking/talking tours and consultations

- poetry and creative writing workshops

- other arts and crafts including drama, photography, music and quilt making

- “living libraries” Footnote twelve

- community ambassadors

- use of technology to mitigate barriers such as physical access for disabled people and people living in poverty (for example, an online forum to record or submit a story)

- provision of transport to Belfast Stories or for story collectors to go to storytellers

- provision of resources to communities, such as recording devices, guidance and facilitators

- community outreach, for example, through story collection days or hubs in community or public spaces

- an ethics advisor

- assurance as to how stories will be used, safely and with respect

- trauma-informed practice and processes

- trained, skilled and properly resourced story collectors and facilitators. Consultees stressed the need for excellent people skills to put people at ease and listening skills to tease out and collect stories accurately

- clear messaging assuring people their stories are valuable and welcome

- clear messaging welcoming the stories of minority communities

- provision of collateral in a range of languages and formats including Braille, large print, audio-visual, BSL, ISL and Irish

People at particular risk of missing out

The role of the community and voluntary sector as trusted intermediaries to engage people, was emphasised throughout the consultation. This included the sector in its widest sense including community centres, residents associations, sports clubs, historical societies, interest groups and arts organisations. Consultees also emphasised a need to go to where people and communities are, rather than expect them to come to a consultation or event, and several organisations volunteered their service.

Other suggestions included:

- press

- social media

- print, radio and TV advertisement

- leaflets

- information available in a range of formats including visuals and video

- events targeted at particular minority groups

- engagement with the Education Authority and schools

- engagement with large employers and their employees

- engagement via libraries

- arts and storytelling events

- pop-up “audience by surprise” events

- sensory and relaxed events

- events in other community settings (such as job centres, hairdressers, bowling greens, play parks, supermarkets, pubs and bookies)

- drop-in hubs

- Zoom consultation sessions

- community ambassadors

- celebrity ambassadors

- word of mouth

The equity steering group

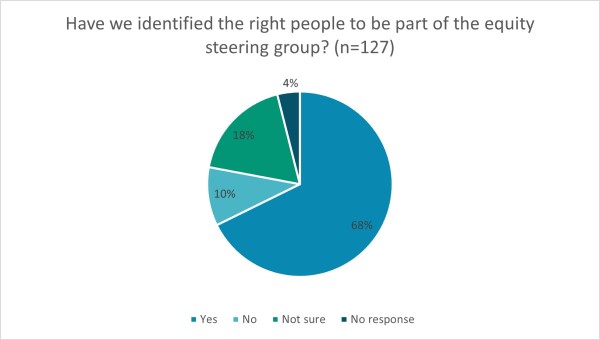

Over two thirds of survey respondents (68 per cent) agreed that we had identified the right people to be part of the equity steering group.

Other suggestions for the equity steering group included:

- Migrant communities

- People with refugee status or seeking asylum

- Men

- Middle-aged men

- The very elderly

- Students

- People of no faith

- Integrated education alumni

- Irish speakers

- Those who no longer live in Belfast or NI

- Parents

- Foster carers and guardians

- Younger children

- People with care experience

- Underprivileged children

- Long-term unemployed

- Different socio-economic classes, in particular people living in poverty

- “Normal working every day people”

- “Less educated people who struggle to read large blocks of text”

- Blind people

- People with dementia

- People from geographic communities

- People living at interfaces

- Homeless people

- Drug addicts

- Tourists

- People who are not affiliated to groups

One person suggested that the equity steering group “Be flexible in its makeup [and] rotates and members can join and leave without it becoming a burden or precious to just a chosen few.”

Some respondents considered more “professional” expertise would be advantageous (“Experts! How are individual people within this massive group of ‘diverse identities’ going to interact with each other? You can’t just pooled such diverse people together and expect to get good quality data”). Others were concerned that the equality focus was misguided or that the steering group was just “box ticking” or “woke” (for example, "If everyone has an equal voice then the result is not proportionate.”).

Responses in relation to the Irish Language

Belfast City Council hosted an Irish language consultation session, which was attended by 19 representatives. There were also three written submissions on behalf of the Irish language sector.Footnote thirteen

Consultees “warmly welcome[d]” Belfast Stories and were “hugely encouraged by the commitment to include diverse stories representing the different identities and people that make up our wonderful city”. However, there were concerns that “the Irish language community have been, so far, completely omitted from the Belfast Stories concept”. Rather,

“it is incumbent upon Belfast City Council to ensure that these rights are catered for in council projects through language visibility. To overlook the language rights of this growing and vibrant community, who have long campaigned for equality and respect, to access such an innovative and important resource through their native tongue would be doing a huge disservice to them, in breach of international and domestic treaty rights and would be contradicting the council’s own Language Strategy”

As well as welcoming the Irish language community, such an approach could also help good relations by “normalising the language [as] research has consistently shown increased visibility leads to increased tolerance and understanding”.

While there was recognition of Irish as a native minority language that should not be categorised with other minority groups, it was also suggested that there should be “members of the Irish language community on the project’s equity steering group, given that all other minority groups across the city are represented.”

“The impact of being unable to access such a magnificent resource in one’s own language is something which should certainly be taken into consideration when evaluating those who may be at risk of missing out. This would ensure that equality, diversity and inclusion are truly at the heart of the Belfast Stories project.”

Other suggestions from the Irish language sector included:

- the Irish language is woven throughout the Belfast Stories themes, including celebration, diversity, education and the story of the language itself.

- there should be bilingual resources throughout Belfast Stories including external and internal signage, exhibitions, marketing and other materials.

- the council develop and implement a language screening assessment for all new council policies, practices and projects.

Responses in relation to Ulster Scots

A meeting was held with the Ulster Scots Agency, and other interest groups also participated in a consultation workshop.

The opportunity to foster further understanding the cultural identity of Ulster Scots was broadly welcomed. It was felt that this should include stories of the language, of “celebrated” and “lesser known” individuals, of industrial heritage and diaspora and international connections.

In general throughout the public consultation, there was concern that there could be an imbalance or bias in content and presentation. One consultee also welcomed further reflection of other Ulster identities and ancestries (for example, Anglo-Ulster, Franco and Italianate).

Footnotes

Footnote eight: Practical Guidance on Equality Impact Assessment, Equality Commission for NI, 2004 (p.36)

Footnote ten: See appendix 6 for a list of organisations that responded via the survey

Footnote eleven: These responses were: “Parking, business as in coffee shops (If you're opening a cafe)”; “Confused why rural needs impact assessment if it is Belfast Stories?”; “Emotional trauma. Anger. Personal regret”; “Impact of climate crisis”.

Footnote twelve: See, for example, www.community-relations.org.uk/news-centre/living-library-where-people-are-books

Footnote thirteen: Conradh na Gaeilge, Forbairt Feirste and Janet Muller