Published: May 2023

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 What is development viability?

- 2.1 Definition

- 2.2 Key principles

- 3 Policy context

- 3.1 Regional planning policy and guidance

- 3.2 Local planning policy

- 4 Key assumptions

- 4.1 Introduction

- 4.2 Overall approach

- 4.3 Benchmark land value

- 4.4 Residential Values

- 4.5 Developer return

- 4.6 Construction and development costs

- 4.7 Other costs

- 4.8 Build to Rent (BTR)

- 4.9 Policy impact

- 5 Strategic plan-wide viability assessment

- 5.1 Introduction

- 5.2 Site typologies

- 5.3 Outcomes of the testing

- 6 Implementation process

- 6.1 Pre-application stage

- 6.2 Planning application stage

- 6.3 Monitoring and review

- 6.4 Section 76 Agreements

- 6.5 Process guide and checklist

1 Introduction

1.0.1 This Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG) provides additional advice and guidance specific to development viability considerations in Belfast. The guidance focuses on residential viability. However, commercial elements (e.g. in mixed use schemes) should be factored into the viability on a case by case basis. It is intended for use by developers, the public and by planning officers in the assessment of planning applications for development within Belfast.

1.0.2 SPG represents non-statutory planning guidance that supports, clarifies and/or illustrates by example policies included within the current planning policy framework, including development plans and regional planning guidance. The information set out in this SPG should therefore be read in conjunction with the existing planning policy framework, most notably the Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS) for Northern Ireland and the Belfast Local Development Plan (LDP).

1.0.3 This SPG is important in creating clarity and transparency for landowners, developers and agents, in terms of how baseline viability has been assessed across the city at the time of developing the Plan Strategy and the mechanisms available to consider viability in relation to individual development proposals as part of the planning process.

2. What is development viability?

2.1 Definition

2.1.1 There is currently no Northern Ireland specific guidance on viability in the development management process. The Council have therefore taken account of best practice in other jurisdictions and have adapted this where appropriate to the Belfast context. For the purposes of this SPG, the Harman Report definition of development viability will be used.

An individual development can be said to be viable if, after taking account of all costs, including central and local government policy and regulatory costs and the costs and availability of development finance, the scheme provides a competitive return to the developer to ensure that development takes place and generates a land value sufficient to persuade a landowner to sell the land for the development proposed. If these conditions are not met, a scheme will not be delivered.[Footnote 1]

2.1.2 Scheme viability is a material consideration in the determination of planning applications where it can be demonstrated that meeting the policy requirements in full may render the scheme undeliverable.

2.2 Key principles

2.2.1 The key principles underlying the Council’s approach to viability considerations in Belfast are as follows:

a) The Council will assume that a proposed development will be viable, unless a developer demonstrates otherwise.

2.2.2 As part of the preparation of the LDP, the Council has tested the impact of proposed policy requirements on development viability, based on best practice approaches to strategic plan-wide viability testing. The policy requirements have therefore been set at a level that ensures most development will be viable.

2.2.3 Assessing the viability of development at the plan-making stage does not require individual testing of every site or assurance that individual sites are viable. Instead, the Council used an appropriate range of site ‘typologies’ to determine the broad principle of development viability based on industry standards and robust local evidence.

2.2.4 This assessment was subject to sensitivity analysis, to examine the effect of changes in individual variables, testing the key assumptions to ensure they were soundly based, before a judgement on the viability of the scheme typologies was finalised. In addition to sensitivity analysis, a contingency factor has been factored into costs associated with each typology example, providing further headroom.

2.2.5 However, it is important to note that a plan-wide viability assessment cannot provide a precise answer to the viability of every development likely to take place over the plan period. Rather, its purpose is to provide a high level assurance that the policies within the Plan have been set out in a way that is compatible with the likely economic viability of development needed to deliver the Plan.

2.2.6 In a case where an applicant considers that they are unable to comply fully with the relevant policy requirements without rendering their development unviable, the onus will be on the applicant to demonstrate why their particular circumstances justify the need for a viability assessment at the application stage. This will be based on identifying which particular assumption(s) are not appropriate to their development or why their development is not represented by any of the site typologies tested.

b) Queries regarding development viability should be raised at the earliest opportunity.

2.2.7 It is up to the applicant (or their representative) to submit what they believe is reasonable and appropriate viability information in their particular circumstances. We would strongly recommend that this form part of a PAD process to help inform a subsequent planning application. This should enable the Council to consider whether an objective review of viability will be required as part of the planning application process. More details on consideration of viability as part of the PAD process are set out in Section 6.1. Importantly in these considerations, the nature and specific circumstances of the applicant will be disregarded, the focus being on key assumptions and unique issues arising from a specific proposal.

2.2.8 The key assumptions to be used as a starting point for site-specific viability testing will be published separately alongside this SPG and will be subject to regular review, as it is acknowledged that over a 15 year plan period the economic outlook, markets and development costs can change significantly. More details on the review process are set out in Section 6.3.

2.2.9 The remainder of this document outlines the:

- Policy context associated with viability (Section 3);

- Key assumptions to be used as a starting point for site specific viability assessments (Section 4);

- Site typologies identified as part of the strategic plan-wide viability assessment and main outcomes (Section 5); and

- Processes associated with site-specific viability assessments (Section 6).

3. Policy context

3.1 Regional planning policy and guidance

Regional Development Strategy (RDS) 2035

3.1.1 The Regional Development Strategy (RDS) makes little reference to the issue of viability. In relation to ensuring an adequate supply of land to facilitate sustainable economic growth (Policy RG1), it outlines the need to assess the viability of sites zoned for economic development uses within area plans.

3.1.2 In contrast, no such viability assessment is referenced in relation to housing land. However, Policy RG8 recognises that there are significant opportunities for new housing on vacant and under-utilised land and Policy SFG2, which relates specifically to the growth of the population of Belfast, notes that an assessment is needed of the scope for higher densities in appropriate locations to help support a drive to provide additional dwellings.

Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS) for Northern Ireland (2015)

3.1.3 The SPPS refers to viability in a number of different contexts, not all of which are directly relevant to the viability assessments addressed in this SPG.

3.1.4 For example, viability is raised in respect of retail developments and the application of the sequential approach to location to protect the vitality and viability of retail centres. The SPPS also outlines the importance of diversity and adaptability to the viability of places. This also applies in the retail context where, continuing to attract investment should not only maintain the existing viability of centres, but also enable them to improve and adapt to changing needs.

3.1.5 Similarly, in relation to the historic environment, the SPPS also notes that the change of use or alteration/extension of listed buildings may be permitted in order to secure the ongoing viability and upkeep of a listed building or historic place.

3.1.6 However, the second use of viability relates more specifically to the economic viability of individual developments. It is also mentioned in the context of economic development, with specific reference to opportunities for mixed use development being identified at the plan making stage where this will help underpin the economic viability of a development as a whole.

3.1.7 This SPG addresses the use of viability assessments in this latter sense, as in the financial viability of an individual development, rather than in relation to the broader vitality of a place or ongoing business profitability (further details on these other issues are provided in separate SPG on Retailing and Town Centres).

3.2 Local planning policy

Belfast Plan Strategy

3.2.1 The Belfast Plan Strategy is the strategic policy framework for the plan area as a whole across a range of land use planning issues. It sets out the vision for Belfast as well as the objectives and strategic policies required to deliver that vision. It also includes a suite of topic-based operational policies.

3.2.2 Viability is specifically mentioned within the policy wording of Policy HOU5: Affordable housing, where it states that the Council will consider suitable alternatives on a case by case basis “where it can be demonstrated that it is not sustainable or viable for a proposed development to meet the requirements of this policy in full.” Further information in relation to this is addressed within the Affordable Housing SPG.

3.2.3 In line with the SPPS, viability is also referenced in Policy BH2: Conservation Areas, requiring that due regard is given to the viability of retention or restoration of the existing building, in considering proposals for demolition. However, there is an overriding presumption in favour of retention and a duty to preserve or enhance the overall character of a Conservation Area.

3.2.4 Similarly, Policy RET2: Out of centre development and Policy RET3: District centres, local centres and city corridors, will only permit retail development outside of existing centres where there is no viable alternative in a sequentially preferable location. Similarly, Policy RET6: Temporary and meanwhile uses will only allow temporary uses within centres where it is not detrimental to a centre’s vitality and viability. In addition, Policy TLC2 only permits the loss of existing tourism, leisure and cultural facilities and assets where it is demonstrated that the facility is no longer viable, recognising the importance of such uses, in particular tourism, to the viability of suppliers, services and facilities.

3.2.5 As noted above, the use of the term ‘viability’ in these latter context is separate to the viability of individual developments addressed in this SPG. Further details on these issues are therefore provided in separate SPG on Retailing and Town Centres.

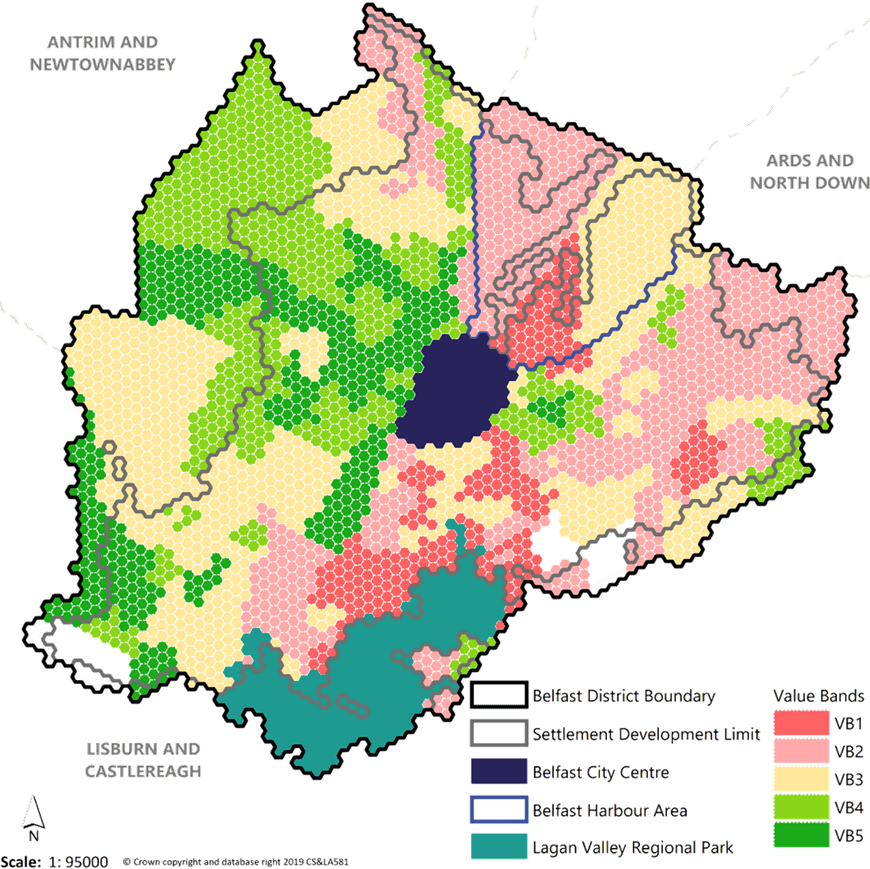

3.2.6 A much broader range of policies are also relevant in the context of assessing viability in planning applications, such as Policy HOU7: Adaptable and accessible accommodation or Policy OS3: Ancillary open space, as meeting these policy requirements in full will require certain features that alter the form of development. The full range of broader policies that were considered as part of the strategic plan-wide viability assessment are outlined in more detail in Section 4.8. Applicants are advised to carefully consider the full suite of local policies together, before progressing proposals for development.

Figure 3.1: Policies relevant to the consideration of development viability

Figure 3.1: Policies relevant to the consideration of development description

Topic based policies

Shaping a liveable place

- HOU5: Affordable housing

- HOU7: Adaptable and accessible accommodation

- DES1: Principles of urban design

- DES2: Masterplanning approach for major development

- BH2: Conservation areas

Building a smart, connected and resilient place

- ITU3: Electricity and gas infrastructure

- ENV2: Mitigating environmental change

- ENV5: Sustainable drainage systems (SuDS)

Promoting a green and active place

- OS3: Ancillary open space

Local policies plan

- Local policies designations

- Land use zonings

- Key site requirements (KSRs)

Local Policies Plan

3.2.7 The Local Policies Plan will set out site-specific proposals in relation to the development and use of land in Belfast. It will contain the local policies, including site-specific proposals, designations and land use zonings required to deliver the Council’s vision, objectives and strategic policies, as set out in the Plan Strategy.

3.2.8 The Local Policies Plan can also set out key site requirements for certain zoned sites which in some cases may include specific guidance in relation to affordable housing, and/or the requirements for other contributions, for example relating to transport, infrastructure, amenity space, neighbourhood facilities etc.

4 Key assumptions

4.1 Introduction

4.1.1 The following section seeks to provide clarity to both developers and planners in terms of the key assumptions used within the viability assessment process. These were the key inputs identified when carrying out the strategic plan-wide viability assessment, which can be used to determine at a high level whether a fully policy compliant development could be viable.

4.1.2 If viability is considered to be an issue for a particular development, it will be up to the applicant to demonstrate whether particular circumstances justify the need for a site-specific viability assessment at the application stage. The weight to be given to a viability assessment is a matter for the decision maker, having regard to all the circumstances in the case, including whether the key assumptions are valid for the specific case. Section 6.3 sets out the review mechanisms which will be applied to the Key Assumptions and for individual assessments at the site-specific level.

4.1.3 In summary, the key assumptions will:

- Assume a reasonable level of profit for the developer;

- Assume a reasonable return for the landowner;

- Understand and allow for consideration of risk;

- Build contingency into costs;

- Take account of all construction, development and financing costs;

- Take account of the delivery method and delivery timescales, and

- Reflect local circumstances.

4.1.4 The sections give a broad overview and explanation of the assumptions made, but the detail of each of these inputs will be published in a separate document alongside this SPG. These will be subject to regular review in accordance with the monitoring framework set out in Section 6.3.

4.2 Overall approach

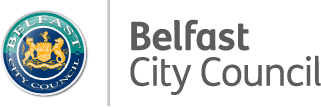

4.2.1 The broad approach taken to viability, for the purposes of this SPG, is illustrated by Figure 4.1. It highlights the importance of the value of development as a measure of the potential for planning obligations to be met, taking account of land value, development costs and developer return. It is also useful in visually showing the need to make robust estimates on land value, for example, which take account of the cost of complying fully with policy.

Figure 4.1 description. The diagram is an offset bar chart illustrating the different components that make up the cost of a development in the middle and right hand bars. This is then compared to the Gross Development Value (left hand bar) to determine if there is any headroom to make a development viable. In the middle bar, the total costs equal the Gross Development Value, with no headroom remaining, whilst in the right hand bar there is residual headroom that can be used to secure land above minimum land value.

4.2.2 As the diagram indicates, if land is overvalued or costs too high, it will reduce the amount available to ensure compliance with all policy requirements and/or the developer’s return. Accordingly, correctly valuing the land ensures that the land is released for development, and that an appropriate developer return can be realised whilst meeting planning obligations in full. Therefore, by definition, reducing costs and or increasing final sale values will improve the viability of a particular scheme.

4.2.3 This methodology, also called the Residual Land Value (RLV) method, is the most appropriate to use for valuing land with development potential when undertaking viability assessment. Essentially, it is an equation where a combination of inputs can be used to calculate the missing element. In the case of a strategic plan-wide viability assessment the assumptions are all standardised, meaning that where the total cost of delivery, including a reasonable return for a developer, equals or is below the total development value, developments are considered viable. Where an element of ‘headroom’ exists, this would allow a developer to compete for land above the benchmark land value.

4.2.4 Where viability is marginal, it is often a matter of balance and judgement between the level of developer’s return and policy compliance. It is therefore important that a developer plans to ensure compliance with all policy requirements when agreeing a price for land, with their return set at an appropriate level to reflect the level of risk. Should a development be brought forward without meeting all policy requirements, regardless of the viability of the scheme, the Council will assess whether this would render the development proposal unacceptable in planning terms, bearing in mind the premise that the obligation is necessary to make the development acceptable. In considering this issue, the council will have regard to the Local Development Plan and all other relevant material considerations. This may result in planning permission being refused, irrespective of any viability considerations.

4.2.5 In summary, the key assumptions used as part of this method of determining development viability are:

- Benchmark land value;

- Gross Development Value (GDV)

- Developer return;

- Construction/development costs; and

- The costs of policy compliance.

4.2.6 These can be viewed in detail within the separate Key Assumptions document, but can be summarised as follows.

4.3 Benchmark land value

4.3.1 As outlined above, part of the approach used in development viability testing is to consider how the residual amount available to purchase land may compare to a benchmark land value, which is an estimate of the lowest value a landowner may release a reasonably unconstrained site for policy compliant development. This takes account of the existing use value of the site along with a premium to incentivise sale.

4.3.2 As there is no single data source for estimating benchmark land values, the key assumptions draw upon a number of sources:

- A database of open market development land transactions provided by private sector sources;

- A database of open market transactions provided under a data sharing agreement by LPS, consisting of validated individual transactions within the Belfast district;

- Development industry workshop discussions;

- Information on land sold for development provided by the Council estates department; and

- Actual figures available from site specific viability assessments received as part of planning applications.

4.3.3 Although benchmark land value can vary according to different circumstances, the key assumptions to be used in viability assessments are standardised estimates. Examples of where specific sites may deviate from established benchmarks include:

- Where the value of existing uses are higher than any proposed alternatives. In such cases it would be expected that the site would remain in its existing use, unless external factors incentivise redevelopment (e.g. public sector grant for regeneration);

- Where there are specific site constraints, e.g. contamination, flood mitigation, access difficulties, protected heritage assets, potential archaeological remains etc. In this case, it would be expected that the costs of dealing with these constraints would have been considered when assessing the value of land; or

- Where sites have a theoretical existing use value that is unrealistic, for example a long vacant site that might have a value for industrial use in a location with a surplus of such land.

4.3.4 An important principle in considering development viability is therefore that land should be acquired at a price that takes into account all known costs, including the costs of complying with all planning policy requirements. The price paid for land will therefore not be considered justification for failing to accord with relevant policies in the plan. In other words, overpaying for land/falls in land value should have been accounted for in the required developer’s return and should not result in non-compliance with planning requirements. It is therefore important that all planning policy obligations, including the provision of affordable housing, should be factored in when considering how much to pay for land.

Alternative use value

4.3.5 Although in most cases the benchmark land value should be used for the purpose of viability assessment, there may be a few occasions where an Alternative Use Value (AUV) should be considered instead. AUV refers to the value of land for uses other than its existing use.

4.3.6 Reviewing alternative uses is very much part of the process of assessing the market value of land and it is not unusual to consider a range of scenarios. Where an alternative use can be readily identified as generating a higher value, the value for this alternative use would be accepted as the land value, i.e. the option with the highest value will be input into a viability assessment.

4.3.7 The circumstances in which AUV will be considered acceptable include:

- Where there is evidence that the alternative use would fully comply with all development plan policies;

- Where it can be demonstrated that the alternative use could be implemented on the site in question;

- Where it can be demonstrated that there is a market demand for that use; and

- Where there is an explanation as to why the alternative use has not already been pursued.

4.3.8 Where AUV is used, this should be supported by evidence of the costs and values of the alternative use to justify the land value presented in the site-specific viability assessment.

4.4 Residential Values

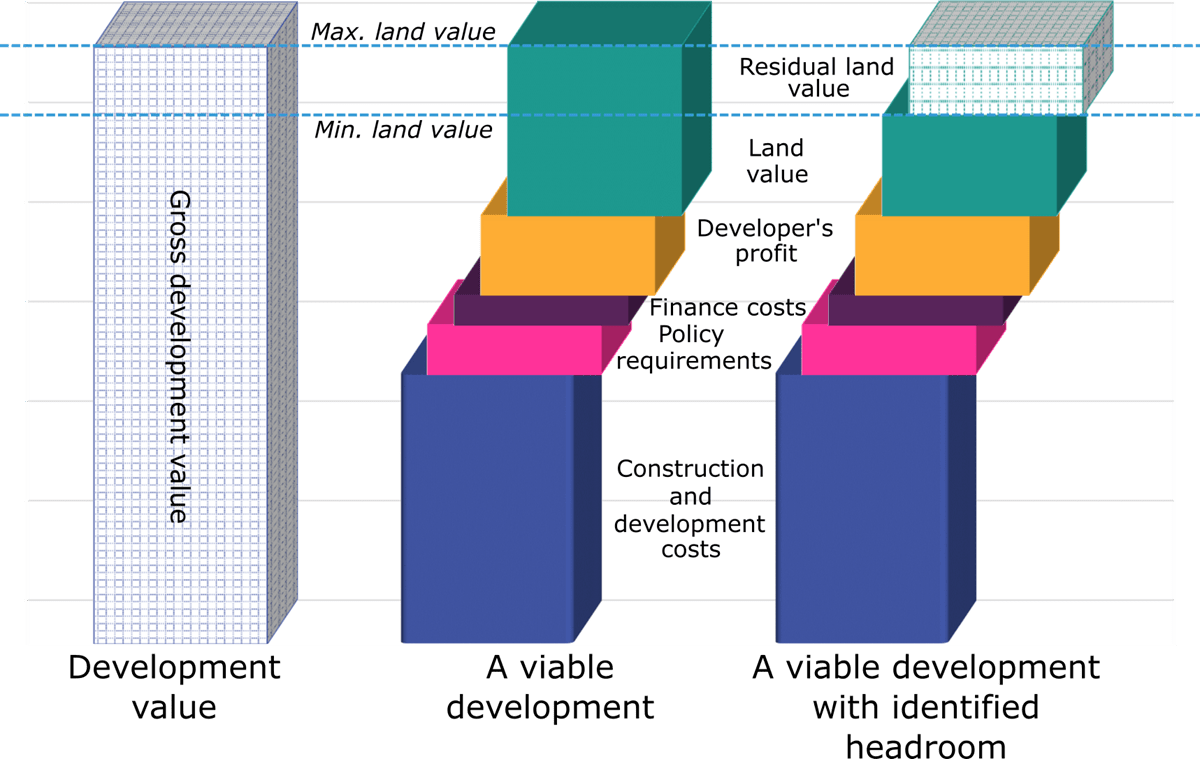

4.4.1 While development costs are considered broadly comparable across the city, values vary significantly. High level research undertaken to inform the Council’s approach to viability assessment paid particular attention to this. Data obtained from the Ulster University House Price and Rental Price Indexes, based on Super Output Area (SOA) geographies, was analysed to identify that the city can be divided up into five value bands, with a further two in the city centre, as illustrated in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 description. The map shows variation in market values in areas outside the city centre. In these areas five value bands are identified. Lower market values are in shades of green, a median value band is shaded yellow, and higher market values are shaded red. Higher market values are primarily concentrated in the south and east of the city with lower market values located in the north and west. In addition to the city centre boundary, the map identifies the district boundary, the settlement development limit, the harbour area and Lagan Valley Regional Park.

Key assumptions

4.4.2 Based on this evidence, residential sales values for different types and sizes of accommodation (houses and flats) were identified for each value band and used in the modelling of a range of site typologies (see Section 5.2).

4.4.3 It will be for the developer to demonstrate which of the value bands any individual scheme falls into, noting that variances can be seen on a street-by-street basis in some locations. We strongly advise the applicant to discuss this with the Council as part of the PAD process. It should also be noted that some large developments may be of a sufficient scale so as to result in changes to the overall sale values in a particular location. In such instances, corresponding adjustments should be made to the value band assumptions as part of any viability assessment.

4.5 Developer return

4.5.1 Potential risk is accounted for in the assumed return for a developer within a viability assessment. It is the role of developers, not plan-makers or decision-makers, to mitigate these risks. Although it is acknowledged that the level of return required will vary from scheme to scheme, dependent on the different risk profiles and the stage in the economic cycle, and that overall returns may be balanced by a developer over a number of development sites, it is necessary in the viability assessment process to use a standardised return. In the majority of cases, the assumptions outlined in Figure 4.3 should be used:

| Type | Cost | Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Social housing | 6 per cent | of base costs |

| All other cases [Footnote 2] | 15 per cent | of Gross Development Value (GDV) |

4.5.2 If a developer can deliver a scheme with lower construction costs or can buy the land cheaper, they may be able to realise a higher return, as long as the planning policy requirements are met in full. Similarly, there may be occasions where a scheme can be taken forward for a lower return. However, the likelihood of the level of return being below 15 per cent does not in itself justify a reduction in planning obligations.

4.5.3 The Council acknowledge that there may on occasion be exceptional circumstances where an applicant believes a proposal requires an alternative return. Such examples could include an unusual type or mix of development, such as the conversion of a historic building, the principle of which is acceptable to the Council, which may not have been considered specifically when setting key assumptions. In such circumstances, the onus is on the applicant to provide satisfactory evidence to support an alternative rate of return.

4.5.4 Given that potential risk is accounted for in this assumed return for developers at the plan making stage, the realisation of risk (e.g. a fall in land values or a rise in costs) would not itself be a reason to claim that a subsequent reduction in return would render a development unviable. Instead, a reduction in the level of return should be considered in the first instance before the Council will consider the reduction of planning obligations on viability grounds.

4.5.5 Where a developer return has been reduced as a result of risk realisation and viability is still a concern, a minimum developer return for a site-specific viability assessment should be agreed with the Council at an early stage, i.e. during PAD discussions. It is important to note in this regard that normally expected returns by any single developer is not the main consideration in such cases.

4.6 Construction and development costs

4.6.1 Development costs can vary due to location, development type, storey height and building use. However, benchmark construction costs for key development types help set a starting point for the consideration of viability. The key assumptions with respect to benchmark construction costs are obtained from a number of sources, including actual figures submitted as part of site specific viability assessments submitted as part of planning applications and are verified in consultation with the development industry. Base development costs per square metre are used for houses generally and apartment schemes of differing heights. These costs should include external works such as plot costs, provision of services and a share of the frontage road and service mains. Full details of these costs can be viewed in detail within the separate Key Assumptions document.

Other development costs

4.6.2 Other costs associated with the development of land included professional, marketing and legal fees and Stamp Duty Land Tax. These are summarised in Figure 4.4.

| Type | Cost | Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Professional fees | 8 per cent | of development costs |

| Marketing fees | 3 per cent | of GDV |

| Agents and legal | 1.5 per cent | of land value |

| Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) | Prevailing rates | per cent of land value |

Historic built environment

4.6.3 As recognised in the policy context, viability is often an important issue in respect of development proposals affecting built heritage. In the case of listed buildings and non-listed buildings within a conservation area, there are a number of different scenarios for which viability becomes a key consideration:

- The policy presumption in favour of retention of heritage assets;

- The need to reduce densities to protect heritage assets which may include addition of extra open space;

- The need to introduce temporary uses to secure the upkeep of such a building;

- The need to incorporate such a building into a new scheme;

- Specialist construction skills are required; or

- Additional costs to retrofit buildings to deliver low/zero carbon heating or improve energy efficiency.

4.6.4 The Council accept that in any of these circumstances there are likely to be additional costs to be considered in a viability assessment. However, where such land/buildings have been purchased for redevelopment, such costs should have been accounted for by a developer when agreeing an appropriate purchase price.

4.6.5 The Council’s overriding concern will be the conservation and/or protection of the listed building and/or wider conservation area in full accordance with the built heritage policies set out in the Plan Strategy. In particular for listed or non-listed buildings in a conservation area, every effort should be made to find an appropriate viable alternative use for the building, which may not be the developer’s preferred use. This should involve placing the asset for sale, or lease on the open market at realistic market values. It is therefore considered appropriate that in all cases where viability challenges are argued in respect of development proposals involving listed buildings or non-listed buildings within conservation areas, a full viability appraisal should be submitted as part of a planning application.

4.7 Other costs

4.7.1 Often, in the case of development and site assembly, various interests need to be acquired or negotiated in order to be able to implement a project. These may include:

- Buying leases of existing occupiers or paying compensation;

- Negotiating rights of light claims and payments;

- Party wall agreements;

- Over-sailing rights;

- Ransom strips;

- Utility company connections / agreements; and

- Temporary / facilitating works etc.

4.7.2 The Council accept that these may be relevant development costs for any specific development and so may need to be factored in as part of construction costs. Where the actual costs are unknown, this can be accounted for as part of any contingency allowance.

Financing Arrangements

4.7.3 Financing arrangements can also be factored into the cost of development, with 50 dwellings employed as a threshold. There is no difference between market and affordable housing in this respect.

4.8.1 Alternative funding models are often used in relation to Build to Rent (BTR) developments, which rely on institutional and/or international investors who must commit to the entirety of a project in one singular and significant monetary investment.

4.8.2 We have taken account of best practice in other jurisdictions. Our research shows that the Built to Rent (BTR) sector has played an important role in the development of city centre living in other locations. The sector generates a range of benefits, including the fact that BTR developers/landlords take a long-term approach to their asset because the return is based on an income over time rather than a capital receipt upon completion of the development. This means there is a greater interest in successfully integrating the asset into the surrounding area and more interest in investing in placemaking. Other benefits include its capacity to be a catalyst for regeneration and its ability to deliver at scale, at speed with quick take-up and occupation and with subsidised and affordable tenures.

4.8.3 The Council therefore recognises the importance of supporting such investors, noting that they normally have the scope to invest almost anywhere in the world. In this context, given that such proposals can’t be phased to recycle funding and that returns are expected over a lifetime of a building, rather than at sale of units in traditional housing, the Council are working to support inward investment by addressing identified risks.

4.8.4 The assumptions outlined in Figure 4.5 can therefore be used for large scale BTR development in the city centre:

| Type | Cost | Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Developer return | 10 per cent (for schemes which are forward funded or sold to an institutional investor) | of Gross Development Value (GDV) |

| 15 per cent (for debt-based investments) | of Gross Development Value (GDV) | |

| Rental yields | 5 per cent | of Gross Development Value (GDV) |

| Rates | Prevailing rate less 10 per cent landlords’ discount | of Gross Development Value (GDV) |

4.8.5 Whilst a maximum of 10 per cent developer return may be accepted, sensitivity analysis undertaken to inform this assumption has shown even lower returns may be viable. Closely aligned to a developer’s consideration of return is the issue of funding and, in particular, funding risk. The bespoke financing model recognised by the Council, includes premium rents, based on Ulster University rental value estimates and a set of industry standard cost allowances. Accordingly, rental yields of 5 per cent are considered appropriate for viability testing purposes, although we acknowledge that specific scheme yields may vary from this. In addition to this, the Council also recognise that the cost of rates (less the 10 per cent landlords discount) is a unique cost in a NI context, which should be netted off the gross rents.

4.9 Policy impact

4.9.1 It is recognised that policies in the Local Development Plan will affect the value and/or costs of development.. As part of the preparation of the LDP, the Council has tested the impact of proposed policy requirements on development viability, based on best practice approaches, and the policy requirements have therefore been set at a level that ensures most development will be viable. The main policies to be considered in this context and how they can be modelled in the testing, is summarised in Figure 4.6.

Figure 4.6: Plan Strategy policies considered in viability assessment

Figure 4.6 description. Figure 4.6 is a spider diagram illustrating the range of policy considerations that help inform the scheme typologies used within the Strategic Plan-wide viability assessment. These include affordable housing policy (that is Policy HOU5), the density of development, which is dependent on settlement areas, the need to increase the size of housing units to meet accessible housing policy requirements (that is Policy HOU7), the requirement to apply BREEAM design standards to non-residential elements of major developments (in accordance with Policy DES2), requirements relating to car parking and servicing (that is Policy TRAN8), and Sustainable Drainage Systems (a requirement of Policy ENV5), and an appropriate proportion of Open Space in accordance with Policy OS3.

Local mitigation measures

4.9.2 All new developments are expected to provide mitigation for local impacts, such as public realm improvements or off-site transport work. Based on a review of recent s76 Planning Agreements in Belfast, an allowance (per dwelling) can be modelled in viability assessments.

Carbon reduction

4.9.3 While the Plan Strategy sets out a number of policies and supporting text that encourage higher standards of sustainability in new development (e.g. DES1, DES2, ITU3), these are not a mandatory set of standards for residential development that can easily be quantified and tested. Whilst they cannot therefore be included directly, sensitivity testing can be used based on costs of carbon reduction from experience in similar jurisdictions, as well as evidence provided as part of detailed viability assessments in Belfast (see Section 5.3 for further details). Full details of these costs can be viewed in detail within the separate Key Assumptions document.

Meeting policy requirements

4.9.4 As previously outlined, in exceptional cases where the Council accepts that meeting the full policy requirements is unviable, an appropriate balance will need to be struck between the level of developer return and the obligations/mitigation required to ensure policy compliance. As every situation is different, each development will be judged on its merits at the time of assessing the planning application. Some of the key considerations that will be used to inform discussions include:

- Developer contributions are seen as necessary to manage and mitigate the impacts of development on Belfast’s infrastructure and/or its environment. Where these are sought, the assumption is that, as they are so directly related to the proposed development and to the use of land after completion, the development ought not to be permitted without it. Consequently, there is likely to be little scope to alter these without fundamental changes to the nature of the proposal itself.

- In respect of planning requirements such as affordable housing (Policy HOU5), there may, in exceptional circumstances, be scope to consider alternative options that would assist with viability, taking account of a number of factors including the level of identified need in an area, the type of residential development proposed and the availability of other suitable sites in the area. The Affordable Housing SPG provides further detail on the range of potential alternative options for consideration.

- With regard to other planning policy requirements, for example housing density and mix, retailing and tourism, conservation areas, etc. there may be some scope for flexibility dependent on the specific site circumstances and the nature of the development proposed.

5. Strategic plan-wide viability assessment

5.1 Introduction

5.1.1 The following sections provide an overview of the outcomes of the strategic plan-wide viability assessment undertaken to inform the development of the LDP. To enable this, a series of hypothetical sites that were representative of the future land supply in Belfast has been identified, providing a number of scenarios to which the assumptions discussed in the previous chapter could be applied.

5.2 Site typologies

5.2.1 As there is no specific guidance in Northern Ireland that sets out how viability testing should be undertaken, the strategic plan-wide viability assessment followed the established practice of assessing the residual value for different site ‘typologies’. These typologies take account of the broad location, size and type (greenfield or brownfield) of land available in the Belfast District. They also reflect the form of development likely to take place on such land and how the sites might relate to the density framework set out in Policy HOU4. The range of policy compliant typologies identified were discussed and agreed at a series of development industry workshops before the strategic plan-wide viability assessment was conducted.

5.2.2 The role of typologies testing is not to provide a precise answer as to the viability of every development likely to take place during the plan period. Rather, as they are hypothetical, they allow the assessment to deal efficiently with the very high level of detail that would otherwise be generated by an attempt to test every site. Accordingly, they can only ever provide evidence of policies being ‘broadly viable’. The testing does however provide a high level assurance that the policies within the plan are set in a way that is compatible with the likely economic viability of development needed to deliver the plan, and is considered robust enough that it should limit the number of cases where individual planning applications require consideration of viability, to exceptional circumstances only.

5.2.3 The typologies used in the strategic plan-wide viability assessment include high density city centre apartments, mixed schemes of houses and apartments and lower density, more suburban housing. The detail of each of the typologies is summarised in the Figure 5.1. Whilst it is accepted that most developments won’t match a typology directly, there should be a typology that is generally representative in terms of scheme size, density, mix, type of development, etc. with which to provide a comparison.

| No. dwellings | Site Size | Density | Dwelling Type | Site type | Sensitivity | Locations tested (see Fig 4.2) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC1 | CC2 | VB1 | VB2 | VB3 | VB4 | VB5 | |||||||

| 1 | Small | Small | Low | Houses | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 2 | Medium | Medium | Low | Houses | Brownfield | 100 per cent social housing/Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 3 | Medium | Small | High | Houses & Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 4 | Medium | Medium | Medium | Houses & Flats | Brownfield | 100 per cent social housing/Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 5 | Medium | Small | Very high | Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 6 | Medium | Small | Very high | Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 7 | Large | Large | Low | Houses | Greenfield | 100 per cent social housing/Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 8 | Large | Large | Medium | Houses & Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 9 | Large | Medium | High | Houses & Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 10 | Large | Small | Very high | Flats/Mixed Use/BTR | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 11 | Large | Small | Very high | Flats/Mixed Use/BTR | Brownfield | 100 per cent social housing/Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 12 | Large | Small | Very high | Flats/Mixed Use | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 13 | Large | Small | Very high | Flats/Mixed Use | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 14 | Very large | Very large | Low | Houses | Greenfield | Carbon reduction/Slower delivery/Phased payments | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 15 | Very large | Very large | Low | Houses | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 16 | Very large | Large | Medium | Houses & Flats | Greenfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 17 | Very large | Large | Medium | Houses & Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 18 | Very large | Large | High | Houses & Flats | Greenfield | 100 per cent social housing/Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 19 | Very large | Large | High | Houses & Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 20 | Very large | Medium | Very high | Flats | Greenfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 21 | Very large | Medium | Very high | Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 22 | Very large | Medium | Very high | Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 23 | Very large | Very large | Low | Houses | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 24 | Very large | Very Large | Medium | Houses & Flats | Brownfield | Carbon reduction/Slower delivery/Phased payments | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 25 | Large | Medium | High | Sheltered | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 26 | Medium | Medium | High | Extra Care | Brownfield | Carbon reduction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Figure 5.1 description. Figure 5.1 is a table which provides a visual summary of the different parameters (listed along the top) that make up the 26 site typologies used within the Strategic Plan-wide viability assessment. This includes whether a typology involved a small, medium, large or very large number of dwellings; the density of development ranging from low to very high; the type of dwellings included, such as houses, flats, build to rent units, a mixture of houses and flats, a mix including non-residential uses, sheltered housing and extra care housing; whether the typology was tested in the City Centre, Wider City or both; whether the site type was greenfield or brownfield; the size of site ranging from small to very large; whether sensitivity testing was applied; and which Value Band the typology was tested with.

5.2.4 Where viability is considered to be an issue for a particular development, it will be up to the applicant to demonstrate why particular circumstances justify the need for a site-specific viability assessment at the application stage. This should focus on identifying why the particular subject site is not adequately reflected in any of the above typologies and why this means the overall viability of the scheme cannot be assumed from the strategic modelling that has been completed. This may also require reference to specific testing assumptions (see Section 4) used in a particular case.

Sensitivity testing

5.2.5 Sensitivity testing, a standard component of development viability assessments, was undertaken as part of the strategic plan-wide viability assessment. This involved varying some of the key inputs to test the impact that this would have on viability. This process assisted with overall analysis and ensured that the conclusions made were as robust as possible.

5.3 Outcomes of the testing

5.3.1 The results of the strategic plan-wide viability assessment are presented as net residual outcomes after all costs including finance, developer return and site benchmark value have been deducted. Where the amount was positive a scheme was considered viable and where it was negative, then such a scheme is not considered viable and could only proceed if some of the factors were different (e.g. a lower rate of return or site value is acceptable, or with some sort of public intervention).

5.3.2 Figure 5.2 provides a summary of the outcomes of the testing, arranged by value band (see Figure 4.2). At the outset, it is important to note that, at a broad level, the plan-wide assessment shows that the majority of typologies tested (which are fully policy compliant, including a contribution of 20 per cent affordable housing) would be viable across the city. In other words, that the policies in the Belfast LDP are realistic and deliverable. Where potential viability issues have been found, this is mainly either as a result of the particular form of development, or in the case of lower-value areas of the city, where market housing prices are lower than actual development costs.

| Value band | Viability summary |

|---|---|

| City Centre Premium |

The key factors affecting viability in these locations are the form of development and market tenure. However with the right building heights, density and tenure, schemes with 20 per cent affordable housing can be delivered. Viability will be particularly sensitive when building heights are above c. 15 storeys (due to higher construction costs) and homes for sale may perform more strongly than the rental market. Carbon reduction measures can be accommodated where development is viable. |

| City Centre |

The key factor affecting viability in the wider city centre is the form of development. With the right size of building and/or form of development, high density flatted schemes with 20 per cent affordable housing can be delivered. As for premium city centre locations, viability in the broader city centre will be particularly sensitive when building heights are above c. 15 storeys (due to higher construction costs), with the very highest density flatted schemes, including BTR development, likely to be marginal. Viability can be improved through a reduction in price paid for land. Carbon reduction measures can be accommodated in most cases where development is viable. |

| Value Band 1 |

The key factors affecting viability in these locations are the form of development and site value. The majority of policy compliant schemes will be viable, including provision of 20 per cent affordable housing – these are most likely to be schemes of all houses or a mix of houses and flats. Higher density flatted schemes, with higher associated construction costs, will be more marginal – in certain cases, viability may be improved by taking a lower expectation of land value. The provision of affordable housing in this area (in whatever ratio of tenures) will not materially change the viability position, and carbon reduction measures can be accommodated. Older persons housing (both sheltered and extra care) is viable, although sheltered accommodation has stronger viability. |

| Value Band 2 |

The form of development is the key determinant of viability in these locations. All policy compliant smaller (up to c. 75 units) schemes of all houses or a mix of houses and flats should be viable. Higher density flatted schemes, with higher associated construction costs, will be more marginal. Where issues arise, adjustments to the development period/phasing of land payments may improve the viability position. The provision of affordable housing in this area (in whatever ratio of tenures) will not materially change the viability position, and carbon reduction measures can be accommodated. The provision of older persons housing (both sheltered and extra care) will be more marginal here in terms of viability. |

| Value Band 3 |

As for Value Band 2, the form of development is the key determinant of viability in these locations. All policy compliant smaller (up to c. 75 units) schemes of all houses or a mix of houses and flats should be viable. The majority of larger developments should also be viable in these locations. However, higher density flatted schemes may be more marginal, and larger housing schemes may be marginal at lower densities (e.g. 300 houses at 30 dph). The provision of affordable housing in this area (in whatever ratio of tenures) will not materially change the viability position. In some cases, the additional costs of carbon reduction measures may render some schemes unviable or subject to delay. Older persons housing (both sheltered and extra care) may not always be viable in these locations. |

| Value Band 4 |

Residential values in these areas make the delivery of any market schemes (including older persons housing) difficult. A significant increase in values from 2019 levels (c. 18-23 per cent) would be required in order to address this. The most likely form of development in such locations will therefore be publicly funded social rented housing. Radical public sector intervention will be required to alter market perceptions and/or to subsidise land/development costs, in order to realise the delivery of more mixed tenure schemes. Some developments may be able to go ahead where localised values may be higher and/or a particular build reduces costs. |

| Value Band 5 |

Residential values in these areas make the delivery of any market schemes (including older persons housing) highly unlikely. A significant increase in values from 2019 levels (c. 50-60 per cent) would be required in order to address this. As for Value Band 4, the most likely form of development in such locations will therefore be publicly funded social rented housing. Radical public sector intervention will be required to alter market perceptions and/or to subsidise land/development costs, in order to realise the delivery of more mixed tenure schemes. Some developments may be able to go ahead where localised values may be higher and/or a particular build reduces costs. |

6 Implementation process

6.1 Pre-application stage

6.1.1 Where it is unviable to deliver a policy compliant development a viability assessment will be necessary as part of a planning application. In such cases we strongly advise the applicant to request a PAD meeting with the Council to discuss the nature of the proposed development and the specific aspects of policy compliance that present a viability concern.

6.1.2 Where a site-specific viability assessment is considered appropriate, the PAD meeting should enable consideration of the following issues:

- Which assumption(s) need to be varied in the specific case;

- Why the proposed development is not adequately represented by any of the site typologies identified;

- The relevant Value Band that the site is located within;

- An appropriate developer return; and/or

- What information will need to be submitted as part of the planning application to allow a bespoke viability assessment to be undertaken.

6.1.3 The onus is on the applicant (or their representative) to demonstrate the need for a detailed viability assessment and to submit what they believe is reasonable and appropriate viability information in their particular circumstances as part of the PAD process. This should enable the Council to advise whether an objective site-specific review of viability is required as part of a subsequent planning application process. The key consideration for the Council is whether a policy compliant development could be delivered that is viable.

6.1.4 Only in the event that the Council is content that there is a valid case will it advise at the PAD meeting that a site-specific viability assessment be carried out as part of any subsequent planning application. However, where a question regarding viability affects the core nature of the proposed development, it may be necessary to undertake detailed viability work as part of the PAD process. In such cases, the Council may retain expert advice in order to review any viability information submitted. The cost of this work at PAD stage will be borne by the applicant and the required fees shall be paid to the Council in advance of the viability information being assessed.

6.2 Planning application stage

6.2.1 Where the Council has advised at PAD stage that a valid viability argument may exist, the submitted planning application should include detailed viability information. This assessment should focus on which key assumptions are being varied and should demonstrate this through the provision of satisfactory evidence. Within the viability assessment, the assumptions that are not being questioned should be held constant to provide clarity regarding the impact of the assumption(s) that have changed.

Format of Viability Assessment

6.2.2 A site-specific viability assessment undertaken to support a planning application should be based on the following factors:

- Assessments should be supported by appropriate available evidence, informed by engagement with developers, landowners, infrastructure and affordable housing providers. They should:

- Provide a full open book appraisal, based on the residual valuation model;

- Include all relevant costs (for example site holding costs, third party interests etc.);

- Clarify the date on which the assessment was undertaken; and

- Include sensitivity testing.

- Assessments should be proportionate, simple and transparent, providing an Executive Summary for publication;

- The actual price paid for land will not normally be a relevant justification for failing to accord with the relevant policies in the LDP; and

- Review mechanisms should be incorporated to strengthen the Council’s ability to seek compliance with relevant policies over the lifetime of proposed developments, and to optimise public benefits through economic cycles.

6.2.3 Complexity and variance is inherent in assessing viability. Whilst a certain degree of knowledge and understanding is required of planners and decision-makers as to the viability implications of all the requirements placed on a development, independent expert viability input is usually required. This specialised input could include, for example, a quantity surveyor to ensure that costings are both accurate and fully independent.

6.2.4 For any viability assessment submitted at planning application stage, all inputs and findings should be set out in a way that aids clear interpretation and interrogation by decision-makers. The assessment should focus on any deviation from the key assumptions outlined in the separate Key Assumptions document, clearly explaining these changes, supported by appropriate evidence. Particular attention should also be paid to setting out the findings of the assessment in a concise and transparent way.

Publication

6.2.5 The Council accept that, in certain cases, disclosure of confidential information could be prejudicial to the developer if it entered the public domain or could cause harm to the public interest that outweighs the benefits of disclosure. This might include information relating to negotiations, such as ongoing negotiations over land purchase, and information relating to compensation that may be due to individuals, such as right to light compensation.

6.2.6 It is therefore the Council’s intention that only the Executive Summary of a site-specific viability assessment will be made publicly available in most cases. As many of the assumptions and costs are standardised (developer return, construction costs etc.), the information should not be commercially sensitive. However, where it is deemed that specific details of an assessment are / may be commercially sensitive, the information can be aggregated in the Executive Summary and included as part of total cost figures, thereby enabling publication with any sensitive information remaining confidential.

6.2.7 In any circumstance, any sensitive personal information will not be published, in accordance with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) requirements.

Executive Summary

6.2.8 As part of any site-specific viability assessment, in accordance with best practice, an Executive Summary should be provided to present the key findings in a way that is accessible to affected communities. As a minimum, this should set out the gross development value, benchmark land value, costs, as set out in this guidance where applicable, and the return to the developer. Appendices 1 and 2 (for BtR schemes) provide templates for the preparation of an Executive Summary to accompany a site-specific viability assessment.

6.2.9 The Executive Summary should refer back to the strategic plan-wide viability assessment and summarise what has changed since then. It should also detail the proposed developer contributions (including affordable housing requirements) and how this compares with policy requirements. In most cases, this Executive Summary will be the only element of the viability assessment that will be made publicly available.

Considerations

6.2.10 The Council will consider the viability evidence provided as part of the planning application and, if required, shall make arrangements for external expertise to assist in making a determination on its robustness. The cost of this assessment will be borne by the applicant and the required fees shall be paid to the Council in advance of the viability documentation being assessed. The Council will make the applicant aware of this at PAD stage, where it has been recommended that a site-specific viability assessment should be submitted with the planning application.

6.2.11 Where the view is established that not all policy requirements and obligations can be met without rendering the proposed development unviable, the aim will be to negotiate a suitable alternative to get as close to the requirements as possible. As noted at the outset of this guidance, the Council’s priority will be to meet the plan obligations wherever possible, not to negotiate an agreeable developer return.

6.2.12 The Council will seek to improve the viability of any proposal and work together with the applicant to find a way to deliver a scheme that meets policy requirements. However, this may not always be possible. In such cases, it will be a matter of judgement as to whether material considerations justify a departure from the relevant policies and whether any potential harm that could arise from failing to meet all policy requirements can be adequately mitigated. If this is not the case, planning permission will be refused.

6.2.13 To assist in this process, there are a number of key questions which the Council will consider:

- Can the developer deliver a viable proposal that is ‘acceptable enough’ in policy terms?

- What are the policy requirements and/or planning obligations that have some degree of flexibility or adaptability in the specific circumstances?

- Do the benefits of the proposed development outweigh the harm of not being fully policy compliant?

6.2.14 In the event that the Council accepts that a development proposal will be unviable if full policy compliance and/or planning obligations/contributions are sought, the following options will be considered in order:

- Deferred timing or phasing:

A delay in the timing or phasing the delivery of a particular requirement may enable a proposed development to remain viable. - Reduced level of obligations and/or contributions:

Where the above option is not sufficient to secure the viability of a proposed development, then a reduction in the level of requirement may be considered. There may be potential to do this for some policy requirements that have flexibility. Any reduction would be limited to the minimum necessary for the scheme to remain viable. The Council may consider building in a review mechanism as part of a Section 76 Agreement to reassess the viability of the scheme at a set point in the future (see Section 6.4). Further detail on potential alternative solutions to policy requirements is outlined in the relevant SPG. - Waiving of requirements:

Only in exceptional circumstances will the removal of requirements and/or obligations be considered, as a very last resort. The nature of the proposed development may also be taken into account, where the Council take into account the other social, community, economic or environmental benefits that would be realised in granting permission for the scheme, i.e. the planning gain arising.

6.2.15 It is important that the decision of the Council on a planning application is based on material considerations at the time of determination, hence the conclusions of a viability assessment undertaken as part of a planning application should remain valid until the date of decision. If necessary, a site-specific viability assessment may need to be updated due to market movements during the planning assessment process.

6.3 Monitoring and review

6.3.1 The council will continuously monitor the outcomes and use of viability assessments as part of the planning process and will provide updates to the separate Key Assumptions document as required. In addition, viability assessments undertaken as part of a specific planning application will be monitored and review mechanisms built into any subsequent developer agreement.

Review of Key Assumptions document

6.3.2 As acknowledged in Section 2.2, the Key Assumptions to be used as the starting point for viability assessments will be subject to review at appropriate intervals over the plan period. This review process will be linked to the in-built sensitivity analysis carried out as part of the strategic plan-wide viability testing undertaken to inform the development of the LDP to assess at what point rising costs or falling values would render development unviable in Belfast.

6.3.3 Where necessary, the separate Key Assumptions document will be updated and published to help inform future consideration of viability. This SPG will also be updated if necessary to address any findings of any updated strategic plan-wide viability testing undertaken.

Site-specific assessment – reappraisals

6.3.4 In relation to site-specific viability assessments, it is acknowledged that the viability of sites may change over time as they reflect current costs and values. For larger, more complex schemes with longer build out rates, the Council may include claw back or overage clauses, or programme in a review and re-appraisal of the viability assessment at particular points throughout the delivery of a scheme. This re-appraisal approach may allow for planning applications to be determined, but leaving, for example, the level of planning obligation, e.g. affordable housing, to be fixed prior to implementation of the scheme.

6.3.5 Careful consideration will be given as to how this will be set out in a Section 76 Agreement, to include a maximum contribution over which the developer would not be expected to exceed, together with a minimum, below which the development would be unacceptable. Clauses will be worded in such a way so as to minimise any potential future costs for occupiers of units within the completed development.

6.3.6 Re-appraisals are generally suited to phased schemes over the longer-term, rather than a single phase development to be implemented immediately. The Council will ensure that the drafting of re-appraisal provisions does not result in earlier phases of a development proposal becoming uncertain as to the amount of development to be provided on site, which would have the effect of stifling delivery. Each phase requires sufficient certainty to be able to provide the required returns and secure development funding.

6.3.7 Similarly, projection models – normally more relevant to large schemes built out over the medium- to long-term – comprise growth models that look at whether currently unviable proposals, based on present day values and costs, might become viable over the short- to medium-term. Such measures can assist the Council where there are concerns arising that schemes that are argued to be currently unviable are likely to be delivered at a much later date, over which time market conditions may vary. A ‘looking forward’ approach by the Council and the applicant can provide certainty for both in terms of defining requirements such as affordable housing, at the time of granting a planning permission.

6.4 Section 76 Agreements

6.4.1 The Section 76 of the Planning Act (Northern Ireland) 2011 provides that any person who has an estate in land may enter into an agreement with the relevant authority (referred to as a Planning Agreement). A s76 Agreement will be required to secure the developer contributions/obligations pertaining to a site.

6.4.2 A Planning Agreement is one[Footnote 3]:

a) Facilitating or restricting the development or use of the land in any specified way;

b) Requiring specified operations or activities to be carried out in, on, under or over the land;

c) Requiring the land to be used in any specified way;

d) Requiring a sum or sums to be paid to the authority on a specified date or dates or periodically; or

e) Requiring a sum or sums to be paid to a Northern Ireland department on a specified date or dates or periodically’.

6.4.3 Development Management Practice Note 4: Section 76 Planning Agreements outlines that such agreements:

"may be used to secure a proportion of affordable housing or social housing in a new development or a mix of tenure in a housing development. This could be where a need has been established, possibly through a policy requirement or as a key site requirement of an LDP and where a condition may not give the appropriate level of detail or security of outcome to be delivered.”

6.4.4 The s76 Agreement referred to above shall be finalised and ready for completion prior to determination of the planning application. Heads of terms are useful when recording what is to be included in a proposed agreement and what is not. Proposed Heads of Terms should be submitted at the PAD stage and agreed by all parties. The items to be included in the agreement will depend on the nature of the scheme negotiated. For all schemes, in the event that required obligations cannot be secured by way of Section 76 Agreement, the Council may refuse the planning application, on the basis that the proposal is unacceptable without them.

6.5 Process guide and checklist

6.5.1 Appendix 3 presents a summary of the key requirements set out throughout this guidance to enable the applicant/developer/agent to check that they have fully addressed the requirements to enable the consideration of development viability as part of the planning process.

Glossary

Alternative use value (AUV)

The value of land for uses other than its existing use. It is usually informative in establishing a Benchmark Land Value. Where appropriate, the AUV should be supported by evidence of the costs and values of the alternative use to justify the land value.

Benchmark Land Value (BLV)

The value of land to be used for any viability assessment. It is established on the basis of the value of its existing use, plus the minimum return at which it is considered a reasonable landowner would be willing to sell their land. The premium should provide a reasonable incentive, in comparison with other options available, for the landowner to sell land for development while allowing a sufficient contribution to fully comply with policy requirements.

Build to rent (BTR)

A term used to describe private rented residential property, which is designed for rent instead of for sale. It offers sustainable, quality investments, providing income from short-to long-term rental contracts that are attractive to large pension funds and property developers.

‘Claw back’ or ‘Overage’ clauses

A clause in a legal contract (s76 Planning Agreement) enabling the Council to review any concessions made in terms of planning policy obligations, should the viability of a particular development scheme subsequently improve.

Gross Development Value (GDV)

An estimate of the open market capital value or rental value the development is likely to have once it is complete.

Local Development Plan (LDP)

The Belfast Local Development Plan (LDP) outlines the Council’s local policies and site-specific proposals for new development and the use of land in Belfast. It will comprise two development plan documents, namely the Plan Strategy and the Local Policies Plan.

Local Policies Plan (LPP)

Part of the Local Development Plan, prepared following adoption of the Plan Strategy. It will set out site-specific proposals in relation to the development and use of land in Belfast. It will contain local policies, including site-specific proposals, designations and land use zonings required to deliver the Council’s vision, objectives and strategic policies, as set out in the Plan Strategy. Together with the Plan Strategy, it will be the principle consideration when determining future planning applications for development in the city.

Plan Strategy

Part of the Local Development Plan, it provides the strategic policy framework for the plan area as a whole across a range of topics. It sets out the vision for Belfast as well as the objectives and strategic policies required to deliver that vision. It also includes a suite of topic-based operational policies.

Planning Obligation

A planning requirement necessary to make development acceptable. They are usually secured by a Section 76 Planning Agreement and run with the land (the application site) in perpetuity. They may be enforced by the Council against the original covenanter and its successors in title.

Pre-application Discussion (PAD)

Provides an opportunity for an applicant to speak with a planning officer and discuss proposals before making a planning application. As part of a PAD, the Council can advise how to make an application, what information will need to be submitted with it and the likely issues when it is considered. The primary objective of the PAD process is to deal with issues early, resulting in a smoother planning application process and quicker decision.

Regional Development Strategy (RDS) 2035

A regional strategy that aims to take account of the economic ambitions and needs of NI and put in place spatial planning, transport and housing priorities that will support and enable the aspirations of the region to be met.

Residual Land Value (RLV)

Part of a method for calculating the value of development land, derived by subtracting all costs associated with the development, including a profit, from the estimated Gross Development Value of a development. It represents the maximum amount a developer could pay for land whilst delivering a viable development.

Section 76 Planning Agreements (s76 Agreements)

A legally binding agreement between relevant parties, normally an applicant, landowner and the Council, under Section 76 of the Planning Act (NI) 2011. S76 Agreements are used to secure a planning obligation, such as developer contributions, where it is not possible to do so by a planning condition. The Planning Agreement must be signed and completed before the planning permission can be issued.

Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT)

A tax imposed by the government on the purchase of land and properties with values over a certain threshold. This tax is payable upon the completion of a purchase, with the rates payable depending primarily on whether the land or property is for residential, non-residential or mixed uses.

Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS)

Sets out regional planning policies for securing the orderly and consistent development of land in NI under the reformed two-tier planning system. The provisions of the SPPS must be taken into account in the preparation of Local Development Plans, and are also material to all decisions on individual planning applications and appeals.

Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG)

Additional guidance which illustrates by example, supports, or clarifies planning policies. Where relevant to a particular development proposal, SPG will be taken into account as a material consideration in making decisions.

Super Output Area (SOA)

Geographical areas developed from Census 2001 information to enable analysis of statistical data on a spatial basis. There are 890 SOAs in Northern Ireland, each representing a population of between 1,300- 2,800 residents.

Typologies

A series of hypothetical development schemes designed to take account of the broad location, size and type of land available in the District and the form of development likely to take place on such land during the Local Development Plan’s lifespan. The range of policy compliant typologies identified were discussed and agreed at a series of development industry workshops before the strategic plan-wide viability assessment was conducted.

Ulster University House Price Index

Ongoing statistics that analyse the performance of the Northern Ireland housing for sale market, the key trends and spatial patterns, providing a robust measure of annual change and an indicator of quarterly change. It is produced by Ulster University in partnership with the Northern Ireland Housing Executive and Progressive Building Society.

Ulster University Rental Price Index

Ongoing statistics that analyse the performance of the Northern Ireland house rental market trends and patterns at a regional level, providing a robust measure of half yearly change and an indicator of annual change. The report is produced by Ulster University in partnership with the Northern Ireland Housing Executive (NIHE) and PropertyNews.com.

Value Band

Areas of the city with similar characteristics in terms of the value of houses for sale or rent. It involved clustering data on sale and rental values for existing housing, new build at the all property level, new build apartments, new build housing (excluding apartments) and the existing market value with new build premium applied (where appropriate) are determined. See Section 4.4 for further details.

Viability

An individual development can be said to be viable if, after taking account of all costs the scheme provides a competitive return to the developer to ensure that development takes place.

Appendix 1: Executive summary template

| Site Address/Location of development | |

|---|---|

| Description of development | |

| Zoning ref. if applicable (see Local Policies Plan) |

| Summary of key assumptions in Site-specific Viability Assessment: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary of housing mix (by tenure type and size) | ||||

| No of units | No of bedrooms / occupants | Size (sq. m) | Type of unit | Tenure |

Assumption |

Amount |

|||

| A) Development Value | ||||

| Gross Development Value | £ | |||

| B) Land costs | ||||

| Benchmark Land Value (including landowner premium) | £ | |||

| C) Construction and development costs | ||||

| Construction Costs | £ | |||

| Professional Fees | £ | |||

| Marketing and Letting | £ | |||

| Disposal Fees | £ | |||

| Contingencies | £ | |||

| Abnormal Costs [Footnote 4] | £ | |||

| Total construction and development costs | £ | |||

| D) Finance | ||||

| Finance Cost | £ | |||