Published online May 2023

Contents

- Introduction

- Policy Context

- Placemaking

- Principles of urban design

- 4.1 Local context, character and urban form

- 4.2 Reinforcing a sense of place

- 4.3 Connectivity

- 4.4 Adapted and connected public realm

- 4.5 Fostering inclusive design

- 4.6 Diversity of land uses

- 4.7 Efficient use of land

- 4.8 Promoting healthy environments

- 4.9 Maximising energy efficiencies

- 4.10 Protection of amenity

- 4.11 Impact of parking and servicing street level

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

1.1.1 Good urban places within our towns and cities, where people live, work and socialise, are influenced by quality placemaking and urban design. Places that are sustainable, inclusive, enjoyable and safe for those using them, contribute to the health and wellbeing of our communities. High quality placemaking and the application of good urban design principles therefore plays a significant role in developing successful places throughout the city.

1.1.2 Successful places are a hive of activity and can provide a range of uses which benefit a diverse range of people. Places are the collaboration of buildings, the spaces surrounding them and associated infrastructure, which evolve and change in response to demands and pressures. Within this changing environment, planning can assist in driving forward high quality placemaking and the application of good urban design principles across all forms of development. An understanding of local context and character is paramount to achieving high quality and sustainable design solutions that successfully integrate new development with the existing built and natural environment.

1.2 Purpose of guidance

1.2.1 This Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG) provides advice and guidance specific to placemaking and urban design. It applies to the Belfast City Council area and is intended to be a point of reference for:

- Planning officers in assessing and making recommendations on planning applications.

- Councillors who make decisions on planning applications.

- Applicants and their multidisciplinary design teams (urban designers, architects, landscape architects, developers and planning consultants), in preparation of applications.

- Communities and their local representatives.

- Other interested stakeholders within the planning process.

1.2.2 This SPG represents non-statutory planning guidance that supports, clarifies and/or illustrates by example, policies contained within the current planning policy framework, including development plans and regional planning guidance. The information set out in this SPG should therefore be read in conjunction with the existing planning policy framework, most notably the Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS) for Northern Ireland and the Belfast Local Development Plan (LDP) Strategy.

2. Policy context

2.1 Regional planning policy and guidance

Regional Development Strategy (RDS) 2035

2.1.1 The RDS provides regional guidance under the three sustainable development themes of economy, society and environment in relation to design issues. Policy RG7 supports urban and rural renaissance by recognising the unique qualities of our cities towns and villages to attract investment and activity ensuring quality urban areas are improved, maintained and enhanced with adequate provision of green infrastructure and the design and management of public realm.

Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS) for Northern Ireland (2015)

2.1.2 The SPPS outlines that good design can change lives, communities and neighbourhoods for the better. It also outlines that new buildings and their surroundings have a significant effect on the character and quality of a place, defining public spaces, streets and vistas and creating the context for future development. Emphasis is placed on placemaking as a people-centred approach to the planning, design and stewardship of new developments and public spaces that seeks to enhance the unique qualities of a place, how these developed over time and what they will be like in the future.

2.1.3 The SPPS states that the key to successful placemaking is identifying the assets of a particular place as well as developing a vision for its future potential. This includes the relationship between different buildings, the relationship between buildings and spaces; the nature and quality of the public domain itself, the relationship of one part of a village, town or city with other parts and the patterns of movement and activity that are thereby established.

2.2 Local planning policy

Plan Strategy

2.2.1 The Plan Strategy provides the strategic policy framework for the plan area as a whole across a range of thematic areas. It sets out the vision for Belfast as well as the objectives and strategic policies required to deliver that vision, based on a suite of topic-based operational policies, including those relating to placemaking and urban design.

2.2.2 The SPPS states that poor design should be rejected, particularly proposals that are inappropriate to their context, including schemes that are clearly out of scale, or incompatible with their surroundings. To this end, the councils placemaking and urban design SPG supports the SPPS in resisting poor design, particularly development which is of poor design quality.

Local Policies Plan

2.2.3 Once adopted, the Local Policies Plan (LPP) will set out site-specific proposals in relation to the development and use of land in Belfast. It will contain local policies, including site-specific proposals, designations and land use zonings required to deliver the councils vision, objectives and strategic policies, as set out in the Plan Strategy. This guidance aims to highlight ways in which these attributes can contribute to positive placemaking within the planning system.

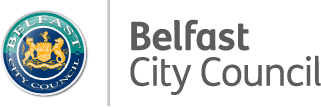

Image 1: Local Development Plan Policy Context

Diagram illustrates how Policy SP5 Positive Placemaking sits alongside a range of strategic policies. Policy DES1 Principles of Urban Design sits below overarching Strategic Policies in particular SP5 Positive Placemaking and its consideration alongside a range of accompanying topic based polices within the ‘Shaping a liveable place’ theme as well as other relevant thematic polices.

3. Placemaking

3.1 Positive placemaking

Policy SP5: Positive placemaking

The council will support development that maximises the core principles of good placemaking in the creation of successful and sustainable places.

3.1.1 A multi-faceted, people centred approach to the planning, design and stewardship of public spaces, placemaking is a transformative approach that inspires people to shape, create and improve their places and spaces. Placemaking considers an areas context, its strengths and weaknesses and is reliant on meaningful collaborative dialogue between those individuals, agencies and organisations that collectively have an interest in how places look, feel and function. The LDP aims to emphasise the benefits of placemaking at the forefront of the development process, as underpinned by the SPPS.

3.1.2 While the built urban environment of the city is diverse, so too are the needs and requirements of those who live, work and socialise there. Ever changing social, economic and environmental conditions will require a greater awareness of how development can have a positive impact on the issues facing Belfast, from improving health and well-being, to protecting the environment and promoting a viable economy.

3.1.3 Strategically Belfast plays a significant role in the growth of the region with the city in more recent years benefitting from increased inward investment, significant regeneration and major growth within tourism and higher education facilities. At a local level, the city plays an even more significant role influencing the daily lives of people. There are areas of the city that are vibrant and diverse and offer a wide range of experiences, however there are also areas that are rundown, disconnected and unwelcoming due to poor design and layout, lack of investment and maintenance. In terms of placemaking, these contrasting characteristics create a number of opportunities for the city to embrace and build upon.

3.1.4 The qualities highlighted within 'Living Places: An Urban Stewardship and Design Guide for Northern Ireland', are outlined and should be pursued by all those involved in shaping our urban environment across the city. The Living Places document defines these ten qualities in detail alongside examples of good, successful places and should be referred to within the development management process where appropriate. A copy of the document can be downloaded from the Department for Infrastructure’s website.

- Visionary – clarity of purpose and direction;

- Collaborative – shared in use, management and planning;

- Contextual – the right fit that reinforces a sense of place;

- Responsible – resource efficient and minimises environmental impacts;

- Accessible – easy to access for all;

- Hospitable – welcoming, safe and healthy;

- Vibrant and diverse – alive with centralised activity;

- Crafted – of excellent design quality and aesthetics;

- Viable – functional, flexible and lasting;

- Enduring – legacy of continued understanding and interpretation.

3.1.5 There is a responsibility within the development process to facilitate changes, whether big or small, that create responsible, resource efficient and liveable places. Effective use of spaces, local features, the built and natural landscape, within a collaborative framework and shared vision, can collectively help achieve the goals set out within the LDP.

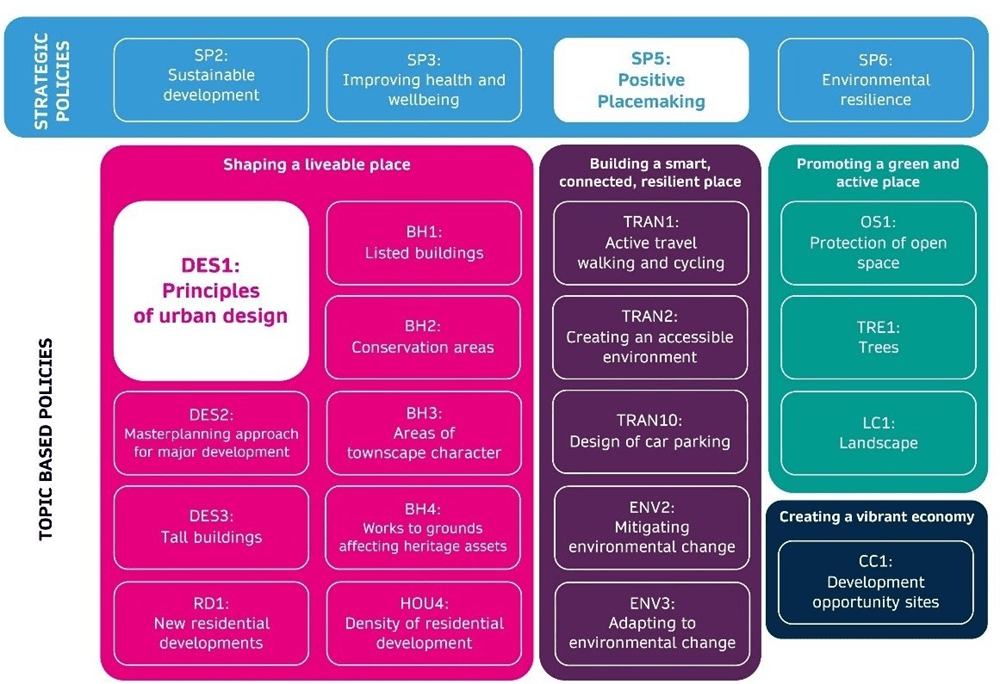

Our place

3.1.6 The Belfast metropolitan area is the largest urban area in Northern Ireland. The city has a complex mix of social and economic relationships, which have shaped its unique urban fabric. New investment and confidence have focused energy onto the form and image of the city, presenting opportunities to capitalise on its unique natural setting and tackle issues of dereliction and gap sites.

3.1.7 It is important that new development is of high design quality which is both achievable and sustainable and helps create places where people want to live, work and socialise. The policies within the plan strategy, along with this supportive guidance, aim to drive standards forward across all development.

3.1.8 Variations in character throughout the city, which can result in an eclectic mix of physical characteristics and architectural styles, offer visually unique experiences. The purpose of this section is to generate greater awareness of the built and natural context by describing elements within it. This understanding helps us appreciate what is special and most sensitive to change and facilitates the ultimate goal of good placemaking, which is about leaving a legacy of high quality places for future generations.

3.1.9 Belfast is a relatively compact city that emerged as a defensive position and castle in the 12th century around the marshy ford where the River Lagan met the River Farset, to protect a ford over the river. It was still a village in the 17th century, the medieval street patterns still apparent to this day. The industrial revolution transformed the city, the arrival of industries such as the linen industry, rope making and shipbuilding caused its expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries. This era has left its legacy on the city as much of its character remains.

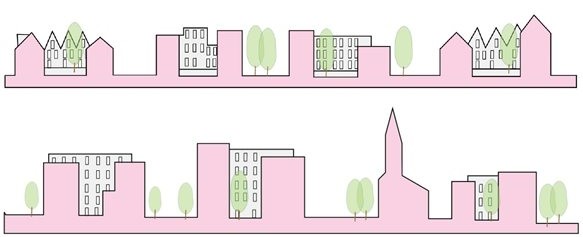

City centre

3.1.10 Today Belfast city centre is distinct and identifiable lying to the west of the River Lagan, and bounded by major roads to the west and north (the Westlink and M3). The southern part of the city centre has a regular grid street and block structure, with a more irregular medieval street structure north of City Hall. Parts of the city retain many of its Edwardian and Victorian buildings marking its evolution throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Although many of the industries that helped expand and build the city have long ceased operations, their presence remains as highlighted by the city's surviving twentieth century buildings and structures such as the Harland & Wolff cranes that dominate the city skyline. The southern boundary of the city is less distinctive as the regular street pattern of the city begins to give way to the residential areas of the suburbs.

City corridors connecting our city centre to the city’s suburbs

3.1.11 The city centre is linked to the suburbs by a number of city corridors (arterial routes). These city corridors not only play an important role in connecting the residential areas of the surrounding suburbs but also function as local high streets. Local activity along city corridors generate nodal points that are vibrant and help create a unique sense of place. As city corridors reach the city centre they also mark the main entrance points to the city, these entrances or ‘gateways’ can act as visual markers within the city and contribute towards a legible and distinctive sense of place.

3.1.12 However not all city corridors are as highly connected as others, many such as Shankill, Crumlin and Falls Road have developed as boundaries between communities. The approach to development along such corridors should aim to reconnect the city to its centre.

The Docks and River Lagan

3.1.13 The Docks and River Lagan have high amenity value within the city, providing it with valuable blue infrastructure that helps support biodiversity and our natural heritage. With regards to its built form, while particular areas lack character and have suffered from the decline in industrial activity, they do however present huge regeneration opportunities for the city.

3.1.14 More recent developments along the waterfront have seen the emergence of new industries linked to film production as well as major tourist attractions such as the Titanic Signature building emerging within the area. Providing accessible connections from the city centre towards these areas, that encourage walking and active transport, are is essential for their further growth and the growth of the city as a whole.

Surrounding hills and coastline

3.1.15 The hills and coastline help define the city and provide not only a unique scenic backdrop but also numerous amenity and environmental benefits that help create Belfast’s distinctive sense of place. This presents an opportunity to further connect green and blue infrastructure throughout the city.

3.1.16 Our communities are in a unique position to enable this, through their knowledge and understanding of the area that surrounds them. Applicants should draw on this knowledge and the guidance in this document to further develop their understanding and in particular its relationship to the site and the development proposed.

3.1.17 The quality of urban areas is also outlined through built heritage designations. The city has numerous listed buildings and monuments, conservation areas and areas of townscape character. These designations are designed to protect and enhance their unique qualities for future generations. The buildings database, which contains records of buildings which have been judged to be of sufficient architectural or historic merit to be surveyed, can be accessed on the Department for Communities website. The many conservation area guides that apply across the city, can be downloaded from the Department for Infrastructures website.

3.1.18 Understanding the distinctive character of urban areas provides the basis for adding to these communities in a meaningful way and enables new development to be designed sensitively. These features, that can contribute to the context and character for development proposals, are outlined in further detail within the following chapters of this guidance.

4. Principles of Urban Design

4.1 Local context, character and urban form

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(a) Responding positively to local context and character through architecture and urban form that addresses matters such as height, scale, massing, proportion, plot width, building lines, rhythm, roofscape, materials and any impact on built and natural heritage.

4.1.1 High quality design is fundamental to delivering positive placemaking. Well-designed places will aim to make meaningful connections with their immediate and wider context to create places that benefit people.

4.1.2 Design development should be a collaborative process, bringing together the skills and knowledge of a wide variety of professionals along with the community from the early stages of the development process.

Local context

4.1.3 Any new development should improve on the existing situation, and at the same time be sensitive to its context. An understanding of the context, history and cultural characteristics of an area and its surroundings will influence the siting and design of new development with the aim of enhancing its positive features and mitigating any negative characteristics. This can help ensure new development contributes to and complements existing communities.

4.1.4 The starting point for any development is an assessment of its site and its surroundings. This covers existing landscape and buildings as well as the social, economic and environmental needs of the existing communities. This widening out of analysis beyond the physical attributes of the site means they are well grounded in their locality.

4.1.5 It is essential that a scheme can communicate its understanding of context clearly and simply. Initial contextual studies demonstrating site analysis, context review and the appropriate response should be undertaken at the earliest stage of the development process to aid dialogue between stakeholders.

Initial contextual studies may include;

- Analysis of the built form of an area, including, height, scale, massing, proportion, plot width, building lines, rhythm, roofscape, materials and the impact on the built and natural heritage;

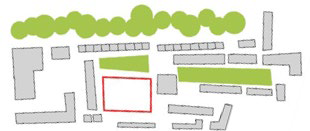

- An assessment of the natural form of an area, its geography and environmental conditions, topography, proximity to flood zones and landscape features such as tree coverage;

- Reviewing the levels of movement and accessibility of an area; walkability, ease of access to cycle lanes and public transport connections as well as traffic flows, parking availability and areas of parking restraint;

- Understanding the mix of uses, daily activities and patterns within the area; residential, commercial, retail, community facilities, leisure/ social venues, open/public spaces and hours of operation (evening/night-time economies);

- Cognisance of socio/economic characteristics such as surrounding demographics, vacancy levels, housing need, crime statistics etc. which while not always visible, will play a key role in the design and layout of proposals;

- An understanding and awareness of these factors and the conclusions arising from this analysis work start to create opportunities within the design process. The detail of contextual analysis should be proportionate to the scale and complexity of the proposal.

Character

4.1.6 Local identity and character are shaped by the history, heritage and culture of place and the people who have lived there. Understanding the history of how an area has evolved is important in determining how it can be appropriately developed. Local character will influence the siting of development in the wider landscape, followed by the layout, pattern of streets and spaces the movement networks within them and the arrangement of building blocks fronting them. It continues to influence the built form, height, scale and massing of the building blocks right through to their articulation and choice of materials.

4.1.7 This is of particular importance when considering the redevelopment and adaptive reuse of existing buildings and larger redevelopment sites. The sustainable reuse of buildings can contribute to the architectural character, historic understanding and cultural heritage of a place, enriching local distinctiveness for present and future generations.

4.1.8 New development within the setting of built heritage assets should aim to conserve, protect and where possible enhance their surroundings. While high quality design does not need to mimic their surroundings, it is important for the design to explain how the development relates to surrounding context and local character through its built form.

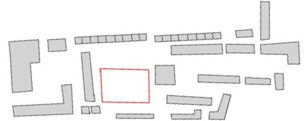

Urban form

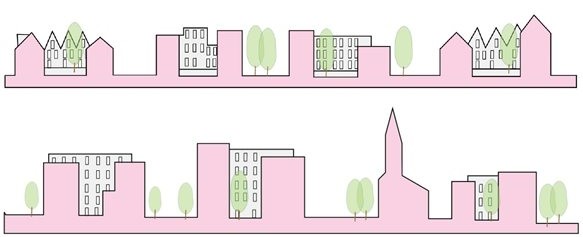

4.1.9 Urban form refers to the function, shape and three-dimensional pattern or arrangement of streets, buildings and spaces. It includes identifiable characteristics such as building scale, height and massing, street patterns, building lines, plot widths, palettes of materials and mixes of uses.

4.1.10 Taking cues from surrounding patterns of development that contribute to the layout, grain and scale of the city’s many character areas is essential, whether this be the civic scale of the city centre and waterfront or the more domestic scale of the suburbs. While each site will have a unique pattern of development that contributes to its distinctiveness, new development should strive to create;

- Compact forms of development that are welcoming, safe and well-connected.

- Sustainable and vibrant communities that are permeable, accessible, and located next to public transport network, services and facilities.

- Recognisable and clearly defined streets that are enclosed by buildings, thereby improving legibility and making it easier for people to navigate.

- Memorable and lasting features, buildings, spaces, uses or activities that contribute to a sense of place.

4.1.11 New development should consider the mix and type of buildings, their form, height, scale and massing as well as their proportions, articulation and materials. Where an area is characterised by consistent features such as narrow plot widths, shoulder heights [Footnote 1] and uniform palette of materials, new development should consider how these features can be interpreted positively within their design approach. Suggested reading includes ‘Close to Home: Exploring 15-minute Urban Living in Ireland’ produced by Hassell/Irish Institutional Property which is driving an new era of locally-orientated and compact forms of urban development.

4.1.12 The ability to identify the positive influence that these elements can have within an urban block or individual building, allows for development to achieve a scale and proportion that is easily recognisable within its context and one which is legible and easily identifiable. Where the scale or density of new development is very different to the existing local area, it may be more appropriate to create a new distinctive character and identity that complements its neighbours rather than scale up the character of the existing place.

4.1.13 It is important to point out that there will be areas within the city that lack a sense of place and local distinctiveness due to poor layouts and design that inhibit permeability and inclusivity. In such places, it may be appropriate to create a new sense of place through established urban design principles that sets a precedent for positive placemaking. The use of cul-de-sacs, which hinder connectivity and fail to promote the legibility of a place, should be avoided where possible.

4.1.14 Historical research can positively inform placemaking, especially within areas of the historic environment where local characteristics have been lost and the opportunity exists to reinstate qualities that enhance local distinctiveness.

4.2 Reinforcing a sense of place

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(b) Positively reinforcing a sense of place by demonstrating that locally distinctive features have been identified, incorporated and enhanced where appropriate.

4.2.1 The identity and character of a place is established not only by the pattern of buildings, streets and spaces, landscape and infrastructure but also by how these spaces are used and experienced on a daily basis. This interaction and the feelings evoked within spaces create a unique sense of place. Sustainable places with a strong sense of place encourage pride and ownership that generates inclusive and cohesive communities where people want to live, work and socialise.

4.2.2 New developments should aspire to improve and enhance the area they sit in. It is important that proposals balance the need to have their own distinctive identity but also one that fits into the established wider identity. This allows development to respond to local character and built form in a way that does not copy their surroundings but instead adds to them through design measures such as;

- Adaptive reuse of existing buildings and landscape features;

- Creatively utilising the built form and materials common to the area;

- Drawing upon the architectural precedents that are prevalent in the local area, i.e. proportions of buildings and their openings;

- Introducing new form that adds interest where appropriate;

- Creating coherent identity that local communities can relate to;

- Reinforcing culture through a mix of uses.

Built form

Movement network

Open space and landscape

Case Studies

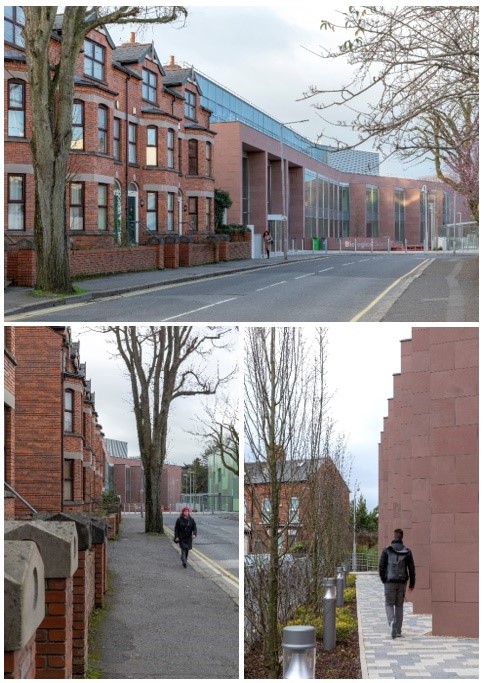

Case Study 1: School of Biological Sciences, QUB

Shortlisted for the RSUA Design Awards 2020, the building design responds to the unique context of the surrounding Malone Conservation Area whilst also carefully considering the constraints of a sloping site which saw a level fall of eight meters. The finished design respects the scale and grain of surrounding streets with a glazed atrium allowing daylight to penetrate all levels of the building.

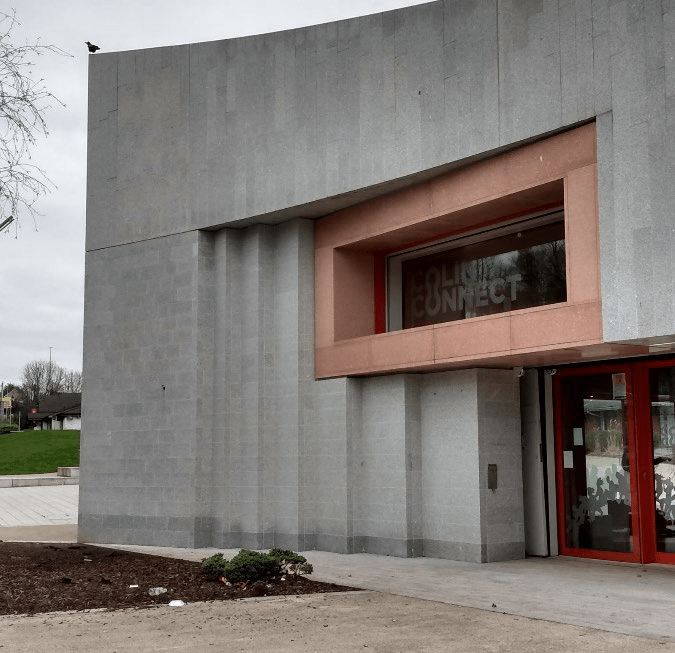

Case Study 2: Colin Connect Town Square

<

4.3 Connectivity

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(c) Providing adequate levels of enclosure and continuity to promote clear and understandable urban form which users can orientate themselves around and move through easily.

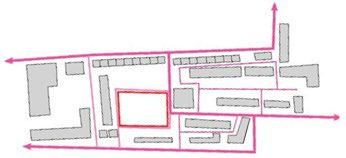

4.3.1 It is not solely the patterns of streets and building blocks that create places, another vital component is the movement patterns of the people utilising them. Ensuring people can walk, cycle and commute via public transport where possible to local services, employment and leisure facilities is crucial to making places sustainable. Development should focus not just on the functionality of the movement of people between destinations, but also on how they can enhance the character and local distinctiveness of their area to create places that people can access and enjoy on a daily basis.

4.3.2 Within the city there are a number of unique and distinctive streets, alleyways and connections that contribute to the permeability of the city such as those that make up the Cathedral Quarter. There are also areas within the city that due to poor design layouts have created physical barriers that are disjointed and difficult to navigate. New development should take the opportunity to enhance the connectivity and permeability of the city and reinstate locally distinctive routes and connections where possible. Consideration should be given to any established 'desire lines' which are often evident where pedestrians or cyclists have worn a path between two points to minimise the distance they have to travel or to create a route that is more convenient in other ways.

4.3.3 Well-designed movement throughout the city can be established through clearly defined streets that are;

- Safe and secure.

- Accessible for all.

- Multi-functional to provide choice to users to utilise active modes of transport.

- Connected with the city’s blue and green infrastructure where appropriate.

- Optimise natural surveillance by ensuring the primary elevations of buildings front onto them and that ground floor uses assist in their activation/animation.

- Designed primarily for the needs of the pedestrian/cyclist and limit the needs of the private car where possible.

Adequate enclosure

4.3.4 Making an area feel safe and secure is an essential component to its success. The scale of development can also impact levels of enclosure. Where spaces are narrow, taller elements may introduce climatic changes that deter users. Within wider vast spaces small scale development could have a negative impact creating vast voids of space that are less welcoming.

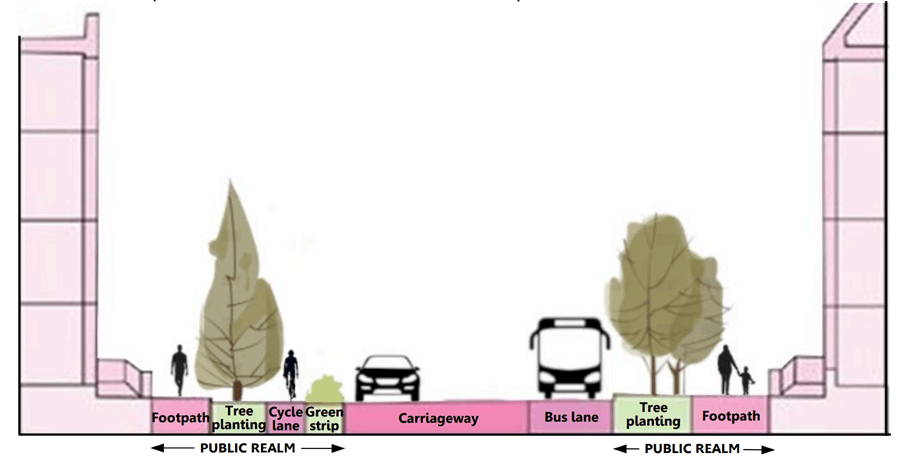

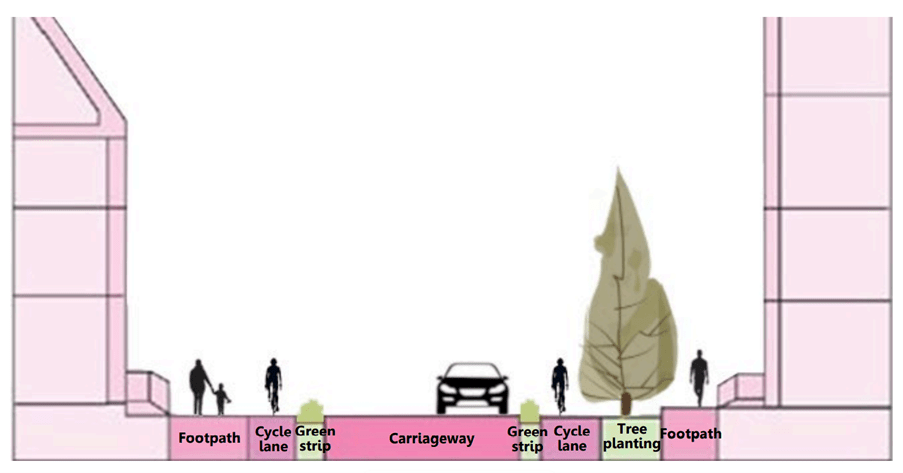

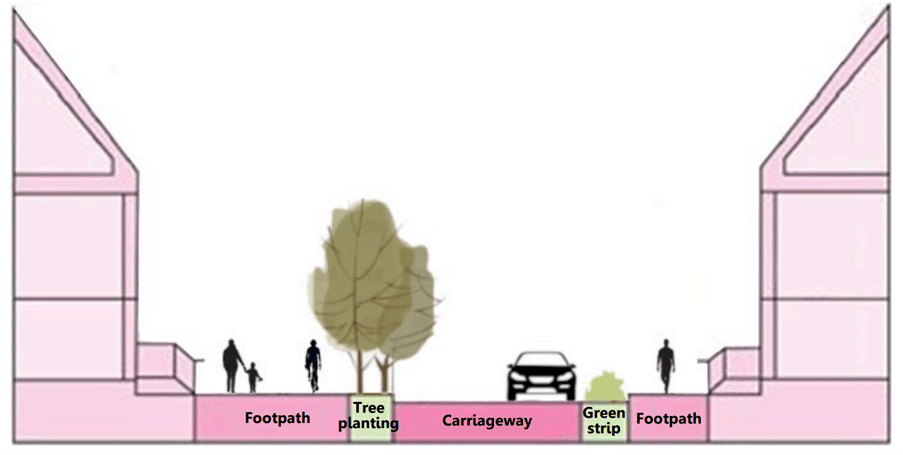

4.3.5 Proposals should therefore take into account the space they wish to create, whether this be a public square, primary street or private courtyard and consider the established pattern of development within the area (see typical street sections included in Section 4.8).

Defining spaces

4.3.6 The spaces between and surrounding buildings are as important as the buildings themselves. It is essential that these spaces are considered early on in the design process to ensure they are contextually appropriate for all intended users. It is also important that a clear demarcation is made between public and private space so that any potential conflicts are minimised. Public spaces are those open to all and include squares, streets and laneways and are vitally important to the efficiency and environmental quality of the city. Development, where appropriate, should front onto and have access from the street or public space.

4.3.7 Within residential, office and mixed-use schemes, it is important to animate public spaces to provide opportunities for social interaction. Spaces should be clearly defined, overlooked and accessible with new development aiming to break down physical barriers to access and movement and contribute to safe, secure and welcoming environments. New development will be encouraged to look beyond the restrictions of site boundaries so as not to preclude a comprehensive and holistic approach that has the potential to integrate with lands beyond the site (see Masterplanning Approach for Major Development SPG).

Private spaces

4.3.8 In general terms, private amenity space should provide a degree of privacy and separation from adjoining public spaces. For the majority of residential developments amenity space will be located to the rear of the development and where possible adjoin onto other private space. However private amenity space can also include balconies within higher density proposals or a combination of private and shared spaces that are accessible to those who can access the property. Consideration can also be given to the incorporation of 'restorative urbanism' that puts mental health and social wellbeing at the heart of the design process. These can include amenity spaces where a small proportion of enclosed space (either communal or singular use) is set aside for rehabilitative functions which can be sensory or educational in nature.

4.3.9 Well-designed buildings should relate positively to spaces surrounding them that are appropriate to their context for those utilising them and others passing by. Appropriately designed boundary treatments can provide a sufficient buffer between private and public space and alleviate the impact of overlooking at ground floor particularly within residential developments fronting onto streets and public spaces. Strategically sited planting and the use of front terraces/gardens with associated gates and boundary structures, can clearly define a space as private and not intended for general public use. It is also important in these cases to create a level of privacy at ground floor whilst maintaining views out to encourage natural surveillance of streets.

4.4 Adaptable and connected public realm

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(d) Creating adaptable and well connected public realm that supports welcoming pedestrian environments.

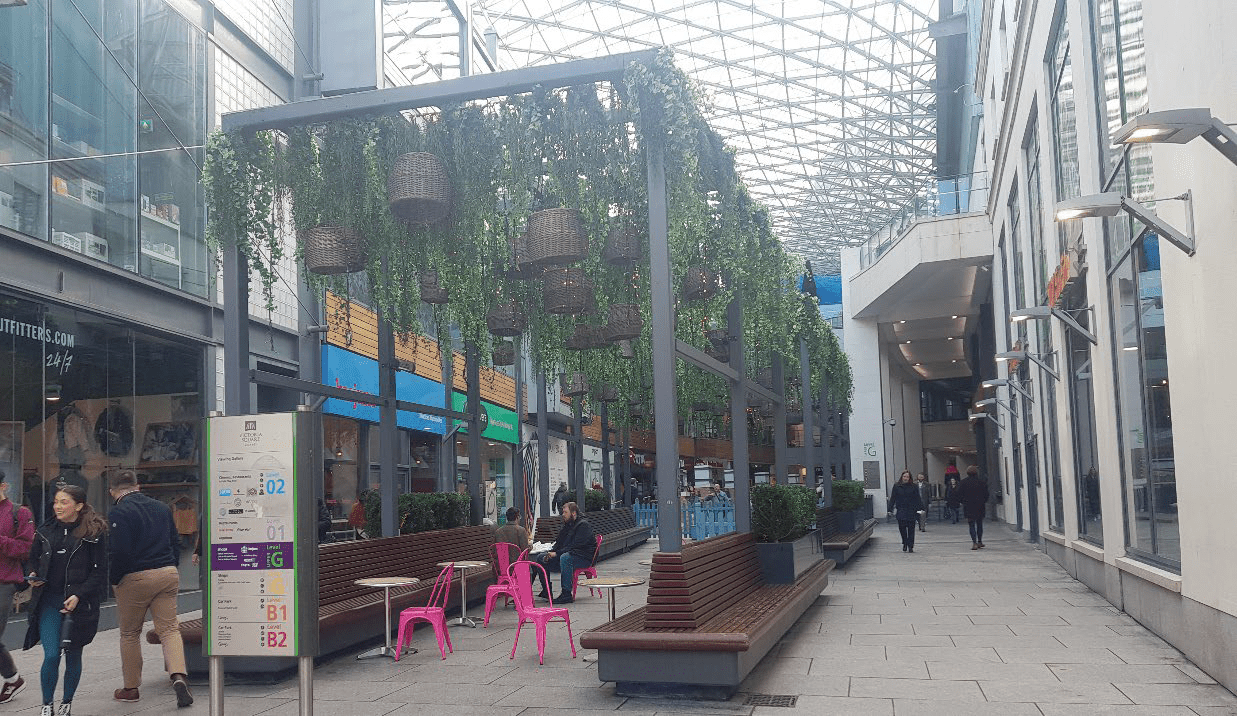

4.4.1 The quality of public realm plays a central role in creating well connected, safe and enjoyable environments. When designed to accommodate a number of uses and encourage a variety of activities, the public realm can encourage social interactions between people and contribute to a feeling of inclusion and community cohesion.

4.4.2 Embedding a diverse range of uses that encourage people to;

- Commute – accessible walking, cycling routes that align with anticipated desire lines and natural sightlines to make legible connections throughout the city.

- Socialise – seating areas, sheltered areas, play areas, sports facilities, and connections to public transport community buildings encouraging people to participate and contribute to a sense of community cohesion.

- Interact – not only with other people using the spaces but also with nature and wildlife to encourage greater levels of biodiversity within the city.

4.4.3 This can be achieved when a space is designed to be flexible and adaptable. Restrictive design and layouts with no connections to main streets and surrounding uses will become underutilised and unwelcoming. Such spaces can attract antisocial behaviour, have a negative impact on businesses and residential communities and can require additional resources to counteract bad design retrospectively.

4.4.4 The design, layout and choice of materials should complement the character of the surrounding context. An integrated approach should be taken in relation to the design and siting of features within the public realm including seating, signage, bins, railings, cycle storage, surface materials, lighting, kerb heights etc. to ensure they are carefully coordinated and integrated within the streetscape and avoid undue clutter that can impact ease of movement within these areas. The positive role that lighting can play in addressing potential anti-social issues should form part of early discussions in the design process.

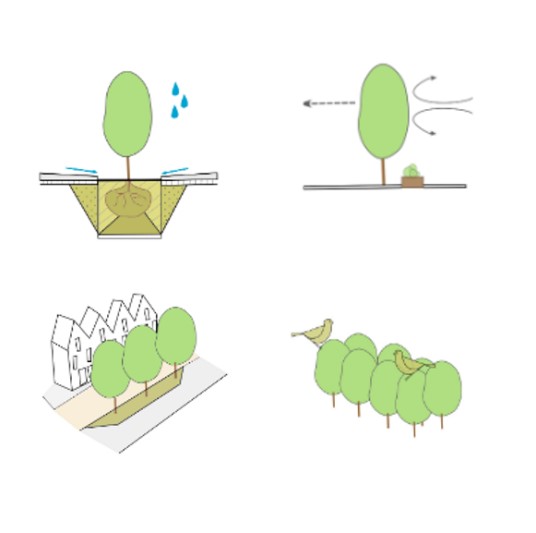

4.4.5 The use of SuDS, trees and planting will also be encouraged throughout the public realm to promote biodiversity and climate resilience within the city. Public realm schemes and new developments should also encourage the connection and utilisation of the cities green and blue infrastructure where appropriate.

Tree planting within developments, along streets and as part of public realm can provide on-site attenuation for surface water runoff. Trees can also mitigate microclimatic conditions such as reducing wind speed, providing shade and allowing light within buildings. They can have beneficial impacts within residential areas by providing screening, reducing noise and improving amenity value. Trees also benefit the wider environment encouraging natural habitats and provide a form of natural carbon sequestration.

4.5 Fostering inclusive design

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(e) Fostering inclusive design that promotes accessibility, supports safe communities and the natural surveillance of public spaces to reduce the opportunity of crime and antisocial behaviour.

4.5.1 Public realm has generally been colonised by vehicular traffic which makes the need for communal and private residential amenity spaces more critical. Increasingly the council has moved to prioritise pedestrian and cyclist use of the city over vehicular use which is stated clearly in the Belfast Open Space Strategy (BOSS). In this regard, new development should strive to meet the play needs of children and identify the design elements required to foster safe-play, particularly within a residential shared space setting. An integrated child-friendly approach reverses the traditional idea that children's spaces should be treated as discreet areas, such as playgrounds, and be excluded from other parts of the public realm. Catering for a 'children's infrastructure' within the network of spaces, streets, landscape and design interventions, can provide an opportunity to create better cities and better outcomes for all generations.

4.5.2 By 2036 one in four of the UK's population will be over 65 years of age. Designing for an aging population and incorporating 'healthy aging' characteristics to buildings and spaces, whereby older people can move more easily and interact with younger neighbours in terms of social support options, can improve health and well being and help reduce isolation. Actively catering for the needs of older residents within the design process can help reduce loneliness and inactivity and have a profound effect on delaying the aspects of frailty and dementia, which are prevalent problems for older people.

4.5.3 The form and appearance of buildings and spaces can contribute to a sense of inclusion and cohesion. Proposals will be encouraged to provide consistent high-quality design to ensure the 10 qualities of positive placemaking are embedded throughout the process. Features that could create actual or perceived barriers, or contribute to segregation, will not be considered acceptable by the council. Collaborative engagement with a variety of stakeholders at the beginning of the process can contribute to the overall success of a development. To ensure a holistic approach to inclusive design, input from users with mobility needs and their associated organisations will be particularly crucial.

Natural surveillance

4.5.4 Successful streets, open spaces, public squares and parks appeal to a diversity of users and activities. This is achieved in places where people feel safe and welcome. The relationship between buildings and the spaces surrounding them can have a significant influence on perceptions of safety.

4.5.5 Features that can help places feel more safe and secure include;

- Highly connected spaces that are clearly defined and convenient for all users.

- Buildings that are located around the edges of spaces.

- Spaces and buildings that have a high level of activity throughout the day and are naturally overlooked.

- Natural lines of direction of travel linking places together.

- Places with a sense of ownership that promote respect, responsibility and sense of community.

- Setting in place clear parameters as to how buildings and spaces are managed and maintained beyond completion.

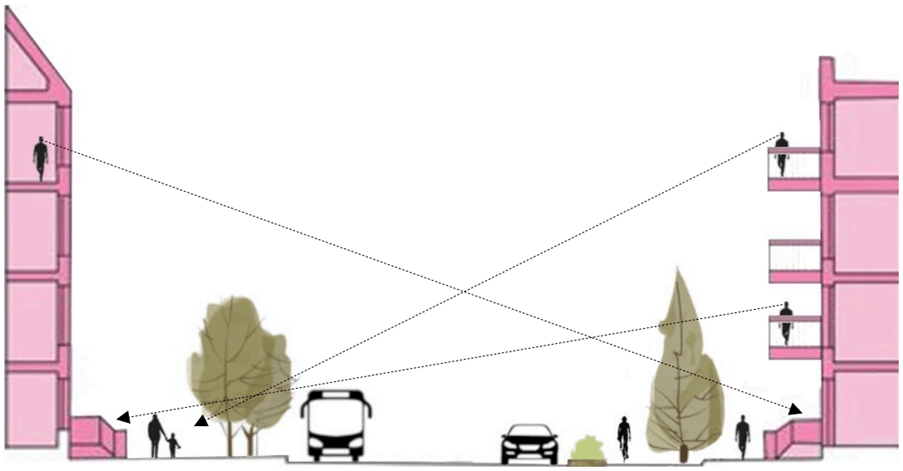

4.5.6 The layout of proposed development should promote a sense of natural surveillance/overlooking. When determining how buildings front the street, the location of doors, windows and balconies and/or external terraces and their relationship with both public and private spaces is critical in creating opportunities for overlooking and the ability for activity to spill out onto the street. This will help create environments that deter crime as it provides ‘eyes on the street’ and a higher chance of detection and awareness. Where necessary security features are required, these should be of high quality design that are appropriate to context and fit in with their surroundings.

4.5.7 Large areas of blank façades and inactive frontage do not contribute to the streetscene, create empty streets with reduced footfall, reduce levels of natural surveillance and encourage anti-social behaviour and should be avoided. A combination of design features can contribute to how secure an area is including adequate lighting, considered landscaping and where appropriate the use of appropriate surface materials to establish the primary use of the space, the combination of which will contribute to how well it is used.

4.5.8 Natural surveillance is maximised within residential schemes when main habitable rooms and primary entrances are located within street frontages, with more private rooms/spaces located to the rear of buildings.

Natural surveillance can be enhanced by providing additional opportunities for eyes on the street. Balconies and higher density living can encourage this when designed appropriately. Inclusive design can make spaces safe and welcoming for people, including carefully placed tree planting and landscaped buffers within public streets in order to separate different modes of active transport and also along the edge of public and private spaces so as to help define these areas.

Image 32: Natural surveillance

Residential scheme recently constructed on the Ormeau Road includes a range of windows and recessed terraces which together with the GF retail units enhance passive surveillance.

4.6 Diversity of land uses

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(f) Promoting a diversity of land uses that provide active frontages and ensure vibrancy throughout the day.

4.6.1 Places that are welcoming and sustainable offer a wide range of uses that help support people to live, work and socialise. They should be well connected to local facilities and the natural environment to help improve sustainability, health and well-being. The mix of uses needed to support communities range from education, healthcare, commercial, spiritual, recreational and civic and each play a vital role in the daily activities of people within them. Within well-designed urban communities, mixed use developments can achieve social inclusion contributing to balanced and mixed communities that are accessible for all. New development should seek to reflect surrounding urban grain and where appropriate incorporate narrow plot widths in an effort to achieve a more diverse range of land uses and avoid overly wide and inactive frontages.

Active frontages

4.6.2 Well-designed buildings that front onto streets and public spaces contribute to the vibrancy and richness of our streetscape. All levels of development can impact the functionality of a space from small retail units to large office blocks and residential units. This is of particular importance where proposals incorporate façades at ground floor. Effort should be made, where the location is appropriate, to punctuate the façade with sections of active frontage to encourage greater levels of natural surveillance that promote safe and vibrant places. Within mixed use schemes, consideration should be given at ground floor to the inclusion of commercial unit’s such as shops, cafes, restaurants and bars. The aim of this approach would be to achieve a level of animation and activity that creates inviting streets that can be occupied throughout the day and into the evening which in turn improves perceptions of safety.

4.6.3 Careful attention must be given to the siting and design of car parking arrangements within new developments. Proposals that include ground floor, semi-basement or surface parking under a raised podium, must ensure they are safe to use and do not impact negatively on the street. Large areas of inactive/dead frontage due to fencing, louvres and ventilation grilles as a result of poorly designed car parking, will not be considered acceptable and every effort should be made in these circumstances to integrate parking provision appropriately.

4.6.4 Consideration should also be given to the location of external storage areas for waste management. Dedicated and suitably designed areas within the boundary of the development should be identified so as to minimise the amount of dead frontage while avoiding undue clutter along streets and access points. Depending on the scale of development it may be appropriate to include a Service Management Plan (SMP) to cover these areas.

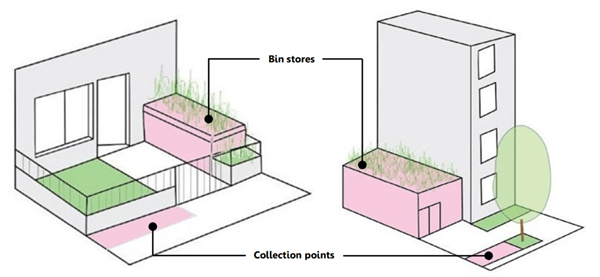

Image 34: Consideration of external storage areas for waste management

If not catered for early in the design process, elements such as bin storage/pick up can have an impact on the streetscene.

4.7 Efficient use of land

DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(g) Promoting the efficient use of land by the development of densities appropriate to site context.

4.7.1 Well-designed spaces and buildings will aim to conserve natural resources such as land, water, energy and materials responding to the growing environmental challenges and demands facing our society. Achieving higher levels of efficiency can be achieved through planning and designing compact communities that encourage people to reduce their energy consumption. By increasing densities, promoting active modes of transport and encouraging people to look after our green and blue infrastructure, we can all play a part in mitigating climate change.

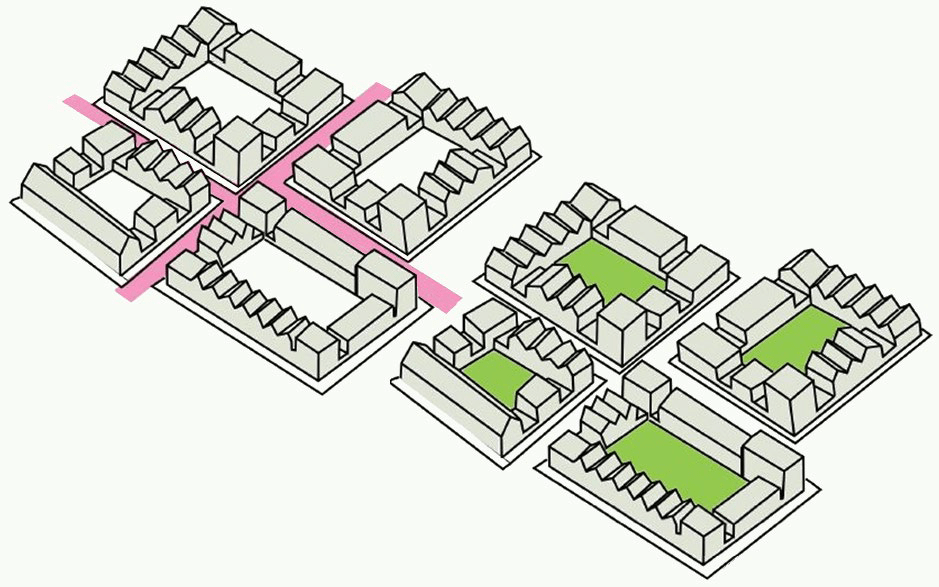

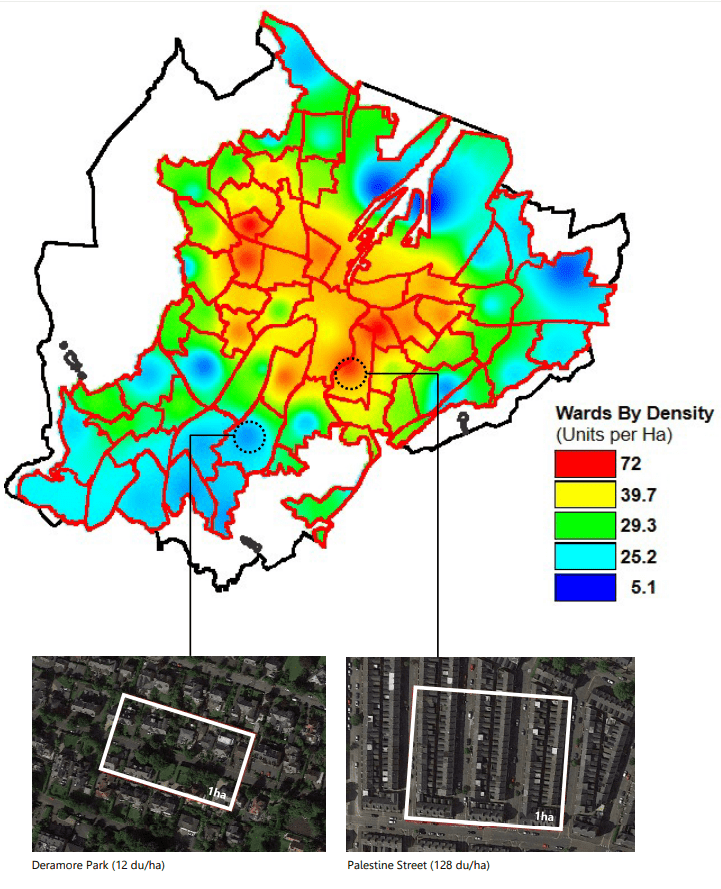

Densities

4.7.2 Density is the degree to which an area is filled or occupied. Measuring and understanding density is a useful way of gauging how land is utilised and can help in determining the efficient use of land for new developments. Density generally refers to the number of units, such as dwellings within a given area.

4.7.3 Sustainable development should be striving to generate a critical mass of people able to support appropriate levels of services in particular locations be these retail, employment, education or public transport. Higher density levels can be appropriate for compact city living, particularly in relation to increasing massing around regional and local centres, public transport nodes, parks and riverfront locations. In these instances, the principles of good urban design would still apply.

Image 36: Density diagram

A heatmap of densities across Belfast ranging from 12 dwellings per hectare (du/ha) at Deramore Park to Palestine Street in the Holylands where densities of around 128 du/ha are not uncommon. This dispels perceptions which can often conflate high densities with high rise.

4.8 Promoting healthy environments

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(h) Promoting healthy environments and sustainable development that support and encourage walking, cycling and access to public transport that maximises connections to the city’s network of green and blue infrastructure.

4.8.1 The success and viability of well designed places is reliant on how connected they are. Developments will be encouraged to provide access to walking and cycling provisions and public transport to facilitate everyday activities and create more sustainable environments. Prioritising pedestrians and cyclists in a way that is safe, convenient, accessible, comfortable and coherent should be facilitated by all within the development process, through the promotion of active travel [Footnote 2] with less reliance on the private car. Streets that have a clear structure and layout and are easily identifiable will help encourage active travel throughout the city.

Hierarchy of streets

4.8.2 Primary streets are busy thriving streets that prioritise pedestrians, cyclists and public transport, but also carry higher traffic flows. Emphasis should be placed on how to safely integrate all levels of transport, providing clear sightlines, signage and indicators of where each transport mode is accommodated. Car movement should be reactive to the speed, volume of traffic and pace of the street to allow all users to feel safe and secure. On key primary streets, emphasis can be placed on creating active transport corridors which differentiate between pedestrian, cycle, public transport and vehicular routes and can be achieved through subtle changes in materials and planting/landscape.

4.8.3 Secondary streets connect primary streets into neighbourhoods and while they can facilitate traffic movement they can also accommodate a number of uses such as on-street seating and spill out spaces. Priority here still remains with pedestrian’s cyclists and public transport with slower vehicle speeds than a primary street.

4.8.4 Local/tertiary streets can take on many forms dependant on the size, character and location of development. They can comprise laneways and courts and tend to be more intimate in character where pedestrian and cycle priorities are maximised. Emphasis should be placed on improving connections with neighbouring walkways and greenways to ensure easy access to employment, leisure and local facilities.

Primary streets can accommodate carriageways, dedicated bus lanes, prioritised cycle lanes, laybys for servicing requirements and planting/green strips. These streets can also include wide footways to accommodate pedestrian movement and commercial spill out.

Secondary streets are largely vehicular routes with clearly designated cycle paths and footpaths.

Tertiary streets should feel pedestrian focused with cycle provision and reduced traffic.

4.9 Maximising energy efficiencies

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(i) Maximising energy efficiencies in buildings through the integration of passive design and renewable energy solutions in their layout, orientation, siting and design, provided the technology is appropriate to the location in terms of any visual amenity or other environmental impact it may have.

4.9.1 New development should seek to provide sustainable, energy efficient buildings, minimising their carbon footprint both during construction and through the buildings lifecycle. While the guidance set out in this section should be applied to all development and outlines minimum requirements, the council will however promote and encourage higher standards where appropriate and achievable. Here consideration should be given to embedding sustainable features within the design of a proposal from the outset so as to avoid retrofitting at later stages. While this may incur higher costs initially, developers should be aware of the impact energy efficient measures will have across the lifespan of the scheme.

4.9.2 When considering the energy efficiency of existing buildings, sympathetic reuse and upgrade may often be the most energy efficient option, particularly taking into account embodied energy and the energy required to demolish and build new. The council therefore encourages the responsible reuse, reappropriation and upgrade of existing buildings with any new interventions being sympathetic to the buildings age, character and construction. Cases may exist where it would be deemed appropriate to demolish the existing building, however these should be treated as the exception and not the norm and supplemented by appropriate justification.

Renewable energies

4.9.3 Well-designed developments should efficiently use and conserve natural resources such as water, energy and materials to help mitigate the impact of development on the environment. Areas where this can be achieved include;

- Reducing the need for energy - maximising natural resources within new development by capitalising on passive measures for light, heat and ventilation.

- Energy efficiencies – making better use of energy sources, managing and monitoring energy use and minimising running costs.

- Efficient use of fossil fuels – new construction techniques such as off-site manufacturing that use innovative, faster and smarter technologies offering quicker production times and greater energy efficiencies.

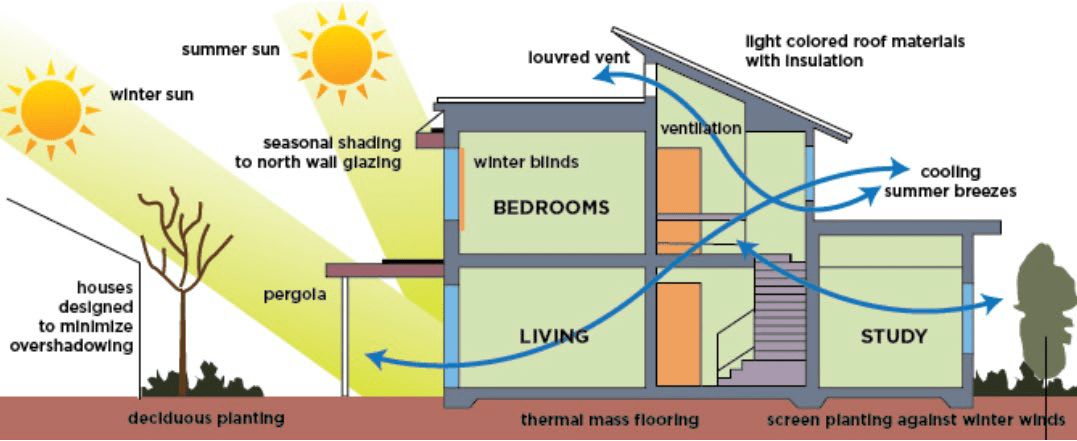

Passive design

4.9.5 Passive design is an approach to building design that utilises the building to minimise energy consumption. Building layout and orientation can have a major impact on energy efficiencies. The orientation of structures on site is critical for efficiency as are the placement of window openings with major glazed areas facing south to take advantage of solar heat gain in winter months when the sun sets lower. New development should make greater use of its immediate context and adapt to its local climate with the aim of minimising overall running costs and any impact on the environment. For this to be achieved development should consider;

- The layout and aspect of internal spaces.

- Insulation of the building envelope and thermal mass.

- Management of solar gain.

- Natural ventilation.

- Construction techniques and materials.

4.9.5 New developments can provide architects and contractors with the opportunities to design and build more energy efficient buildings. Here the ultimate goal would be to construct a net-gain energy building which through renewable energy resources consumes less than or equal to the amount of energy it produces on site.

4.9.6 The type of construction and selection of materials within a development will influence its energy efficiencies. Carefully chosen materials that aim to reduce the environmental impact of development can be achieved through;

- Designs that are based on typical manufacturing standards that aim to reduce unnecessary waste;

- Incorporating high thermal or solar performance to reduce lifespan costs;

- Locally sourced materials that aim to reduce the carbon footprint of transporting to sites.

Image 40: Passive design solutions utilise natural movement of heat, air and light to keep internal building conditions comfortable. Site planning should consider where to position buildings and rooms within buildings with gardens making the most of existing landscape, topography and orientation.

As a Civic Trust Award Regional Finalist in 2021, Erskine House comprises Grade A office accommodation in addition to active retail space at ground floor. The 8-storey development has also achieved BREEAM rating ‘Excellent’.

4.10 Protection of Amenity

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(j) Ensuring no undue effect on the amenity of the neighbouring properties or public spaces by minimising the impact of overshadowing and loss of daylight.

4.10.1 In order to achieve sustainable developments throughout the city, it is important to consider their functionality. Well-designed homes and buildings should aim to create attractive and welcoming spaces that provide high quality amenity value for all intended users and also for those simply passing by. They will also consider the impacts of servicing and utilities to ensure they are efficient and well-integrated within communities.

4.10.2 Safeguarding daylight and sunlight within existing and nearby buildings is essential in creating quality internal and external spaces and should be carefully considered from the outset of the design process. This is of particular importance in the case of residential developments. Inadequate access to daylight and sunlight can cause issues affecting levels of privacy, security, and enclosure, and can also impact microclimates surroundings development.

4.10.3 Developments should therefore take account of;

- The design and layout of internal spaces, window placements and in larger scale developments the incorporation of light wells and atriums to ensure comfortable spaces for those using the buildings;

- Externally the height, scale and massing of a building and its proximity to its neighbours will affect the levels of daylight and overshadowing of the spaces surrounding it;

- Other factors such as the siting of trees and landscaping, whether existing or planned as part of the development, will need to take account of whether there is sufficient levels of light.

4.11 Impact of parking and servicing at street level

Policy DES1: Principles of urban design

Planning permission will be granted for new development that is of a quality, sustainable design that makes a positive contribution to placemaking by:

(k) Ensuring that on-site vehicle parking provision and movement, where required, and any external bin storage areas do not have a negative impact at street level which would result in the creation of dead frontage or unnecessary clutter.

4.11.1 Parking and how it is accommodated within development schemes can have an impact on the overall design quality of a place. Well-designed car and cycle parking will need to be considered as part of most developments within the city. There are a number of design requirements needed when locating safe and integrated parking facilities that prioritise the pedestrian experience so as to avoid creating car dominated streets. Due consideration will need to be given to how pedestrians and cyclists move through parking areas with specific attention paid to DDA requirements and Part R Building Regulations

4.11.2 Careful consideration should be given to car and cycle parking within residential and commercial developments to ensure they are located sensitively in a way that allows them to visually integrate within the development. While their location and design should ensure that parking facilities are convenient and safe to use for all, including occupants, employees and visitors.

4.11.3 Parking facilities should not dominate a development and result in large stretches of dead or inactive frontages that contribute to unattractive environments. They should be designed to prioritise the movement needs of people over cars particularly the needs of those more vulnerable residents including children and the elderly. Consideration should also be given to the use of larger heavy standard tree planting which would reduce opportunities for illegal street car parking and be robust enough to withstand vehicle collisions and anti-social damage.

4.11.4 Where surface cycle/car parking is proposed these should be well-designed with both hard and soft landscaped features to help soften their appearance. The opportunity can also be taken to break up large areas of surface car parking with tree and shrub planting which again can help mitigate any visual impact and also contribute to improved environmental conditions such as air quality and levels of biodiversity.

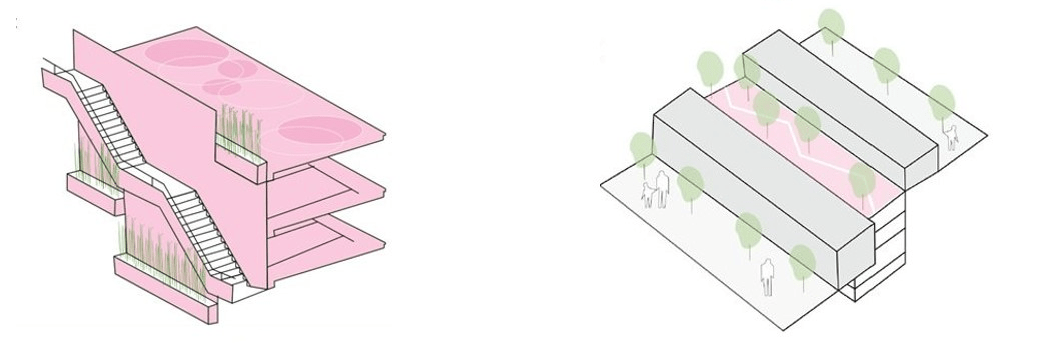

4.11.5 Multi-storey car parking facilities within development proposals should also be well integrated, be of high-quality design and where possible incorporate green infrastructure. It may also be possible to cater for additional uses within the development to encourage adaptable and sustainable environments that promote compact city living. This could include infrastructure at roof level such as urban agriculture, pocket parks and play in an effort to improve the health and wellbeing of users. Electric charging points should be considered within the layout and design of parking arrangements so as to avoid unnecessary additional costs if retrofitted at a later date. SuDS and green roof design solutions should also be considered at an early stage. A Service Management Plan (SMP) may be required for larger development schemes and should reference green infrastructure where appropriate.

Servicing and utilities

4.11.6 The servicing of new developments should be considered from the early stages of the design process so as to avoid retrofitting measures later on. This is to ensure development is serviced well without impacting the quality of design or experience of those within the area. Elements such as bin storage, utility services and facilities such as water, sewage, drainage, gas, electricity and digital infrastructure while all vital components of new developments, if not handled sensitively, can have a detrimental impact at street level. Careful consideration should therefore be given with respect to;

- Their location and design and any potential visual impact at street level, with the aim of avoiding unnecessary clutter.

- Their ease of access for maintenance and repair.

- The adaptability of these elements to adjust to advances in technologies.

- The provision and integration of adequate refuse and recycling facilities, including provision of any necessary temporary pick-up areas.

4.11.7 If not carefully considered at the outset of the design process, common issues that can arise include;

- Visual clutter - caused by impact of bins placed along street, in residential front gardens or within commercial forecourts.

- Obstruction to movement – bins can restrict footways and impede pedestrian and cycle movement, which can be particularly problematic for wheelchair users, the visually impaired and people with pushchairs. They can also impede the views of drivers and potentially impact adversely on road/highway safety.

- Odour and public health – poorly designed bin storage areas can result in odour problems which can impact on residential amenity. Uncontained refuse areas can attract vermin and introduce the potential for disease and infection.

4.11.8 Bin storage areas should be appropriately designed so that they are easily accessible and well-integrated within the proposed layout. In the case of residential development, bins should be stored in easily accessible yet visually unobtrusive locations, ideally to the side and rear of properties. Where this is not possible, areas to the front of the property may be acceptable but should be adequately designed and integrated to minimise visual impact. The choice of enclosure materials can reflect that of the building or incorporate screen planting. In larger schemes, where euro bins are often used, dedicated, unobtrusive storage areas should be identified to the side and rear of the development with separate accesses provided for residential users, commercial users and refuse collectors. In larger schemes where euro bins are normally used, dedicated, unobtrusive storage areas should be identified to the side and rear of the development. Here designs should provide separate access for users and refuse collectors.

Images 42 and 43: Servicing and utilities

Where bin storage is placed to the front of the development, it should be considered and designed as an integral component to the overall arrangement. Within larger schemes external bin stores should be easily accessible an integrated within the overall design.

Plant facilities

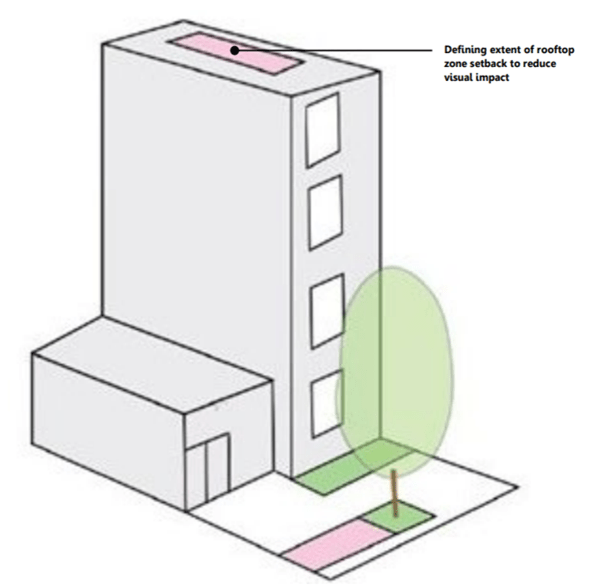

4.11.9 Where additional ancillary facilities and servicing are required to be located at roof level, such as lift/ stair over runs and air handling equipment etc, their siting and design need to be considered carefully so that their visual impact is mitigated and that they do not unduly add to the scale and massing of the building. Proposals with additional plant should be kept to minimal heights and incorporate considerable setbacks and/or screening to avoid any visual impact from street level.

Image 44: Plant facilities

The siting of ancillary roof plant/equipment should be considered early in the design process and where possible sufficiently set back and screened to minimise any visual impact.

Footnotes

1 The building shoulder height, is the sheer height of a building at the back of the footway up to the eaves or parapet height. It is recognised that many buildings may have one or more additional storeys above this height as a set-back element.

2 The term ‘active travel’ includes those who walk, wheel and cycle.

Image credits

Images contained within this document are subject to copyright restrictions and cannot be reproduced without the owners permission.

Image copyrights are owned by Belfast City Council, except where stated;

| Description | Photo credit |

|---|---|

| School of Biological Sciences, QUB | White Ink Architects |

|

65-67 Fitzroy Avenue |

Studio Rogers Architects |

| Weaving Works, Ormeau Avenue | RMI Architects |

| Spórtlann na hÉireann, Coláiste Feirste, Falls Road | ArdMackle Architects |

| Erskine House, Chichester Street | TODD Architects |