Published in December 2020

City facts: Belfast

- Belfast population: 343,542 (2019 mid-year estimate)

- Aged 25 or under: 33 per cent

- Belfast accounts for 18 per cent of the population and almost 30 per cent of all jobs in NI.

- Residential units completed in city:103 (2019/20)

- Fulltime median gross weekly pay: £575 (2019)

- Household waste recycled and composted: 44 per cent

- Street trees: 11,500

- 77.3 per cent of the population live within walking distance of a park or play area.

- Average annual temperature: 9.2˚C

- 68 per cent of households have access to one or more cars.

Before COVID-19...

- 53 per cent of all journeys taken by car

- 29 per cent of all journeys taken by foot

- 2 per cent of journeys per person by bike

- 18.2 per cent of population aged 16-64 have no qualifications

- 35.6 per cent of the working age population is educated to NVQ level 4 and above

- 80 per cent of businesses are micro (0-9 employees)

- 21 per cent of those claiming unemployment benefits are aged 18-24

During COVID-19

- 3,737 positive cases per 100,000 of population (in Belfast as of 14 November 2020 (highest in NI)

- 270 deaths in Belfast

Future proofed city - Belfast Resilience Assessment

Foreword from the Commissioner for Resilience

Finalising the first Resilience Strategy for Belfast, while the city endures the effects of a global pandemic, is a poignant reminder of why cities need to prepare for risk, no matter how unlikely they appear to be. COVID-19 has taught us many things about how cities respond to crises, of the value of community networks, and the importance of good connectivity.

Put simply, the pandemic has exposed our weaknesses. Our lives have changed immeasurably as a result of a global shock, but the impact will be felt differently nationally, and locally, and those impacts will be determined by the scale and nature of existing vulnerabilities. Put simply, the pandemic has exposed our weaknesses. We now face the challenge and opportunity to put resilience at the heart of our re-build.

The draft Resilience Strategy, published in January 2020, presented a series of potential shocks and stresses for the city of Belfast. It is not an exhaustive list. Each one by itself represents a risk to the city. However, it is the relationship between these risks, and the scenarios that may emerge if several occur at once, that presents the greatest challenge for Belfast. I made several conclusions about Belfast’s exposure to risks. In particular, the potential impacts of climate change on the city. I highlighted the city’s lack of preparedness and the lack of a coherent city-wide approach to climate change. I suggested the identification and development of ‘multiple problem solvers’ - levers which can respond to and resolve several risks at once.

The arrival of the pandemic resulted in an extension of the public consultation on the strategy. The passage of time has enabled us to start work on many of the priorities identified in the draft document. We have therefore, made excellent progress this year in developing a series of measures on climate adaptation, climate mitigation and levers to support a green economy. We have established two important city-wide structures to take this work forward; a Resilience and Sustainability Board to drive delivery of this strategy and the Belfast Climate Commission, to act as a think-tank and advisor for the city’s climate action. I am extremely grateful to my co-Chairs and to the members of both boards for their commitment and dedication during such a difficult year. We have managed to accelerate our work in this area, and as a result our final Resilience Strategy looks markedly different from the draft- because so many programmes and priorities have commenced and begun to deliver outcomes for the people of Belfast.

I am also very grateful to the Resilient Cities Network for their generous support to Belfast through this process; to our strategic partner ARUP for their advice throughout and to Urban Scale Interventions (USI) for coordinating our conversations at community level.

“Belfast is emitting 1.5 million tonnes of carbon a year. At this rate, we will have used up our carbon by 2030.”

A Net-Zero Carbon Roadmap for Belfast

This strategy has two distinct parts: (1) a Resilience Assessment, an analysis of the strategic risks to Belfast, taking account of the views of city-wide stakeholders and (2) an Ambitions Document, setting out the vision and priorities being delivered by the Resilience and Sustainability Board. I am delighted that we now have a strategy and a set of city partners now working with a singular focus on the transition to a net zero-emissions economy.

In a relatively short period of time, the city has moved from lack of preparedness for climate change to one of proactivity, partnership working and ambition. The challenges set out in the draft strategy have been embraced by city-partners. It is to their credit that Belfast is now better prepared for the future, and over time, its people will increasingly be better protected. This is the essence of resilience work.

This final strategy has been amended and improved based on the contribution of residents from across Belfast. Communities have demonstrated their interest in, and understanding of the importance of a long-term focus on risks, and have shown their commitment to projects and programmes that will future-proof their city. I have personally benefited from listening to people from across Belfast, and have no doubt that the ambitions in this document are much more likely to succeed because of them.

Grainia Long

Commissioner for Resilience

December 2020

Foreword from the Chair of Strategic Policy and Resources Committee

Welcome to Belfast’s draft Resilience Strategy. For the first time, partner organisations across the city have worked together to identify the strategic risks that we face, today and into the future. Furthermore, we have collectively agreed an ambitious goal to transition to an inclusive, zero-emissions economy in a generation. Achieving this will require urgent action, and I am delighted that our city partners have committed to thirty programmes, to be delivered collaboratively to future-proof our city, and make us climate resilient.

There has rarely been a more important time for Belfast to build its resilience. A major public health crisis, and a combination of economic pressures, climate-related events, and social change are taking globally and impacting locally. To improve our readiness and ultimately ensure our recovery, we must have a sophisticated understanding of the risks we face.

The strategy has been informed by more than a thousand conversations, and many hours of data crunching - we are grateful to everyone who has contributed.

Only by working together across the city communities, schools, nursing homes, businesses and agencies - can we really be ready to face complex challenges, from pandemics to economic shocks and climate change. I am grateful to members of the city’s Resilience and Sustainability Board for the leadership they have shown in developing this strategy, and I look forward to seeing the positive effects arising from delivery.

Councillor Christina Black

Chair

Strategic Policy and Resources Committee

Contents

Executive Summary

- Delivering the Belfast Agenda

- What is urban resilience?

- Characteristics of a resilient Belfast

- Resilience challenges in this decade

- Methodology

- Case study in urban resilience: Fire at Bank Buildings

Shocks and stresses for Belfast in 2020

- Infrastructure capacity

- Condition of existing housing stock

- Public health

- Flooding and extreme weather events

- Cyber resilience

- UK exit from the EU

- Economic recovery capacity

- Poverty and inequality

- Population change

- Carbon intensive systems

- Climate change

- Housing supply in the city

- Segregation and division

- Mental ill-health

- Use of prescription drugs

- Governance and financing of risk

- How we will deliver this strategy

Appendices

Executive Summary

- Urban resilience is the capacity of cities to survive, adapt, and develop no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience.

- The Belfast Agenda, the city’s community plan, included a commitment to take a targeted approach to issues which pose the greatest risk to the city, its economy and its people.

- In doing so, Belfast has been an active member of the Resilient Cities Network, working globally to reduce vulnerabilities, and making cities better prepared for the future.

- This strategy delivers on the Belfast Agenda commitment. It includes an overview of the major risks facing the city. The ‘Resilience Assessment’ outlines the shocks and stresses that could make the city more vulnerable and could weaken our capacity to resist and to recover from future challenges.

- It is the intention of the Resilience and Sustainability Board that the Resilience Assessment be reviewed and refreshed every two years to ensure a proactive approach to the management of strategic risks.

- The second half of the document outlines our ambitions: one goal, three ‘multiple problem solvers’, and 30 programmes for delivery.

- A genuine collaboration between city partners and residents, this strategy will drive progress to deliver the city’s goal to transition to an inclusive, net zero-emissions, climate-resilient economy, in a generation. It commits Belfast to a step-change in this decade, reflecting the scale of climate breakdown and its implications for Belfast.

Our goal

To transition to an inclusive, net zero-emissions, climate-resilient economy in a generation.

Shocks

- Infrastructure capacity

- Public health

- Cyber resilience

- Condition of existing housing stock

- Flooding and extreme weather events

- UK exit from the EU

Stresses

- Economic recovery capacity

- Climate change

- Mental Ill-health

- Poverty and inequality

- Housing supply in the city

- Use of prescription drugs

- Population change

- Segregation and division

- Governance and financing of risk

- Carbon intensive systems

We have identified three ‘multiple problem solvers’ - where we tackle several shocks or stresses at once.

A strategic focus on each of these areas will build the city’s resilience, over time. They are:

- climate adaptation and mitigation

- participation of children and young people

- connected, net zero-emissions economy

The strategy contains 30 transformational programmes, agreed by city partners, to prepare the city for this century. This includes an important focus on how we fund and manage risk.

Context

Delivering the Belfast Agenda

The Belfast Agenda vision for 2035

“ Belfast will be a city re-imagined and resurgent. A great place to live and work for everyone. Beautiful, well connected and culturally vibrant, it will be a sustainable city shared and loved by its citizens, free from the legacy of conflict. A compassionate city offering opportunities for everyone. A confident and successful city energising a dynamic and prosperous city region. A magnet for talent and business and admired around the world. A city people dream to visit.”

The Belfast Agenda commits the city to the appointment of a Commissioner for Resilience to work with partners to develop a strategy to take a targeted approach to addressing those issues which pose the greatest risk to the city, its economy and its people.

Since 2018, Belfast has been a member of 100 Resilient Cities, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. GRCN* is a 2035 global network of cities, all focused on identifying and reducing urban threats - either immediate shocks or systemic vulnerabilities. It comprises Belfast’s biggest global network to date. Since the establishment of the ‘Resilient Belfast’ team, Belfast is working alongside cities like Barcelona, Sydney, Cape Town and San Francisco to solve urban problems, and strengthen the fabric of the city. This work has culminated in the production of this Resilience Strategy, which includes a range of commitments to de-risk the city, making us more adaptable, prepared for the unpredictable and increasingly our capacity to thrive. This Strategy will help the city to mitigate risks to deliver the Belfast Agenda.

* The Global Resilient Cities Network was previously known as 100 Resilient Cities.

This Resilience Strategy is one of several documents that aim to deliver the Belfast Agenda and its core objective of inclusive growth.

- The Belfast Agenda

- Draft Local Development Plan

- Future proofed city - Belfast Resilience Strategy Assessment

- Future proofed city - Belfast Ambitions Document: A Climate Plan for Belfast

- Cultural Strategy

- Open Spaces Strategy

- Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan

- Good Relations Strategy

- Inclusive Growth Strategy

What is urban resilience?

Urban resilience is the capacity of cities to survive, adapt, and develop no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience.

Being a resilient city does not mean the city is without risk - urban resilience refers to cities that are exceptional at predicting, managing and responding to risk. Resilient cities are highly adaptive.

Working alongside one hundred cities globally, Belfast has been learning the benefits of a focus on preparing for immediate and longer term risks.

“Belfast’s capacity to withstand and embrace disruption and change in the coming decades is critical to its economic, social and environmental future.”

Our vision in the Belfast Agenda could be undermined, if we do not learn to adapt to and cope with shocks, such as floods or cyber attacks. COVID-19 has highlighted the city’s existing vulnerabilities, and the impact of the pandemic puts the achievement of our Belfast Agenda priorities at risk, unless we take coordinated action, as a city. Furthermore, some stresses such as climate change can be ‘risk multipliers’, exacerbating existing weaknesses.

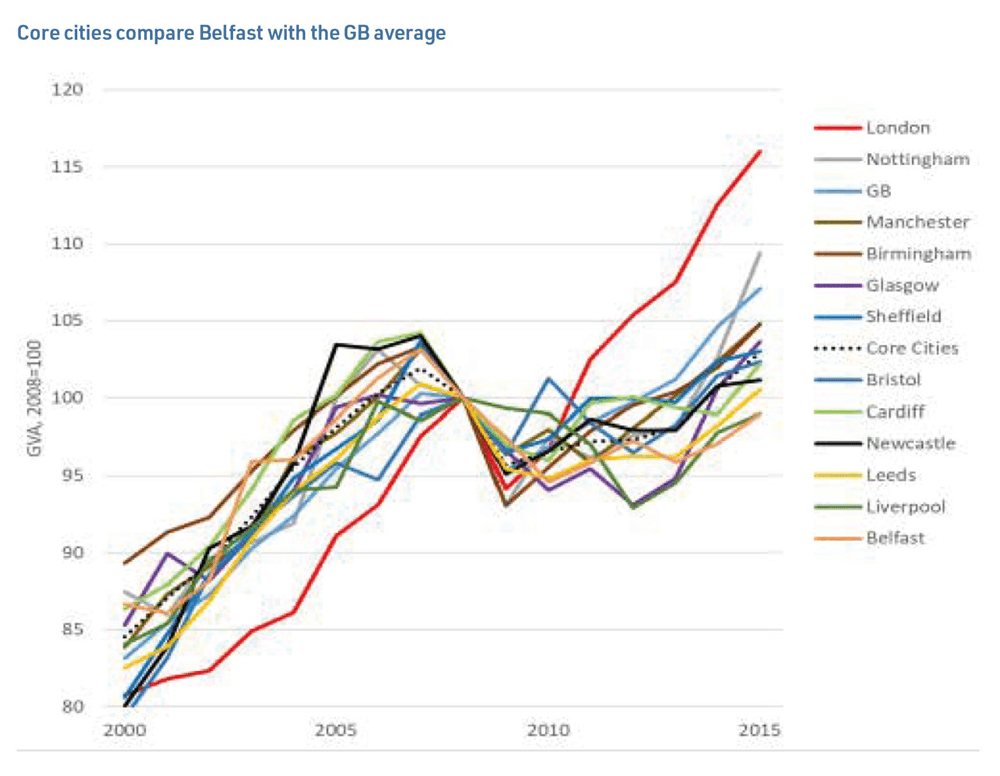

Belfast’s economic resilience is a good case in point. The capacity of a city to respond to economic shocks is a strong indicator of its resilience.

“Building Belfast’s economic resilience - its ability to adapt to and cope with economic shocks - is essential.”

Belfast’s capacity to respond to the recession of 2008-10 has been weak - demonstrated by its low levels of productivity since 2007 and when compared with other cities, it has shown weak levels of ‘good growth’ since the financial crash.

Furthermore, the impact of economic growth has traditionally been unevenly spread throughout the city, prompting a city-wide focus on ‘inclusive growth’ in the Belfast Agenda. Building Belfast’s economic resilience - its ability to adapt to and cope with economic shocks - is essential.

This may mean building new forms of capacity to take on different types of pressures, to withstand them and recover from them.

Whether impacted by an adverse weather event or an economic recession, the following systems all determine how a city bounces back. However, evidence would suggest that the number and diversity of local community and voluntary groups in the city, and their inter-connectedness, has been a highly valuable social asset in the initial response to COVID-19 and has arguably strengthened the city’s capacity to cope with the effects of the pandemic. This resilience strategy emphasises the city’s assets as well as its vulnerabilities, and evidence in relation to both has informed the document throughout.

Resilience thinking is not a luxury but a necessity for cities. It is about putting in place holistic and integrated measures to enable cities to adapt, survive, and thrive regardless of the stresses or shocks they face.

Singapore Resilience Strategy

The seven qualities of a resilient city

| Qualities | Information |

|---|---|

| Reflective | Using past experiences to inform future decisions |

| Resourceful | Recognising alternative ways to use resources |

| Inclusive | Prioritise broad consultation to create a sense of shared ownership in decision making |

| Integrated | Bring together a range of distinct systems and institutions |

| Robust | Well-conceived, constructed and managed systems |

| Redundant | Spare capacity purposefully created to accommodate disruption |

| Flexible | Willingness, ability to adopt alternative strategies in response to changing circumstances |

Characteristics of a Resilient Belfast

- We will be risk aware - with a strong understanding of exposures that (1) make us vulnerable (2) could knock us off course

- We will ensure there is capacity ‘in the system’ to respond to shocks

- We will de-risk investment by improving our management of risks at a city level

- We will have collective agreement at a policy level on the ‘top risks’ and coherence around a plan!

- We will integrate networks so we are better able to withstand shocks

- We will include resilience indicators in how we measure the performance of our city

- We will demonstrate strong resistance to shock - often through resilient infrastructure - i.e. integrated into all capital projects

- We will develop multiple problem solvers - approaches that solve several problems at once

Resilience challenges in this decade

2020

COVID-19

The global pandemic struck the people of Belfast in spring 2020. As of 14 November 2020, 223 people had lost their lives due to COVID-19.

2018

Fire at Bank Buildings

On 28 August, a fire destroyed Bank Buildings, a listed building in the heart of Belfast city centre and its retail district. 14 businesses within the cordon were unable to reopen for over four months. Pedestrian and vehicle access across the city centre was affected causing a significant drop in footfall in the area.

2017/18

Major storms

Ex-Hurricane Ophelia in 2017, Storms Ali and Calum in 2018 There were a range of storms bringing high winds in 2017 and 2018 and causing electricity outages and damage to infrastructure. Schools, businesses and public services were affected.

2014

Coastal flooding

The threat of tidal inundation to Belfast city centre and over 4000 homes across the city led to the deployment of 45,000 sandbags and the preplanned closure of basements and businesses in the Harbour area. Millions of pounds of damage was caused to infrastructure around the coastline of NI.

2012

Flooding

Flooding occurs on an annual basis affecting properties and infrastructure. There was significant flooding in 2012, 2009, 2008 and 2005 with thousands of homes being internally flooded.

2012/13

Flag protests and civil unrest

Following a vote to change the number of days the Union Flag is flown at Belfast City Hall, there followed a period of almost daily protests. There were resulting impacts for the performance of the local economy.

2010/11

The big freeze

Five weeks of extremely low temperatures led to widespread impacts on infrastructure including homes, schools and businesses. Frozen pipes cracked during the thaw causing so many leaks that mains water supplies were significantly depleted. 40,000 premises lost water supplies and over 60,000 premises became subject to rotational supplies.

Methodology

A well-established methodology - adopted by 100 cities globally - was used to develop this strategy, and build the city’s resilience capacity.

The City Resilience Framework (CRF) was developed by our strategic partner ARUP and helps identify the complex and interdependent issues that contribute to a resilient city. The CRF is used by all partners in the 100RC network and facilitates cooperation between cities. Our relationship with ARUP has led to the development of a city risk and asset audit, a climate change risk assessment and a study that will help us to develop our strategy for child friendly neighbourhoods.

A number of steps in working towards our goals and vision were put in place. Each step carefully considered and carried out as we:

- Mapped our city’s vulnerability and risk against potential actions.

- Engaged with partners citywide in Belfast to gather evidence and formulate possible solutions.

- Commissioned a city risk and asset audit by ARUP to quantify and identify shocks and stresses.

- Assessed and analysed multiple data sources to inform decisions, test assumptions and steer our initial conclusions. This also involved commissioning our own studies.

- Informed our thinking by requesting from ARUP a Climate Change Risk Assessment and a study on developing our strategy for child friendly neighbourhoods.

- Engaged across our city for over three months on our strategic areas of focus to engage and attract feedback.

- Working in partnership with Urban Scale interventions we engaged with more than 1,000 people across the city. This included public area based events, focused workshops, on street engagement through the tea kiosks in the city centre and online thematic workshops with youth and older people. The online public consultation also created 62 responses and we received 12 written submissions.

With these seven steps, we have embarked on the next stage of the journey towards a resilient Belfast.

Step 1

City Resilience Framework identified areas of city resilience

| Information | Rating |

|---|---|

| 1 Meets basic needs | Area of strength |

| 2 Supports livelihoods and employment | Area of strength |

| 3 Ensures public health services | Area of strength |

| 4 Promotes cohesive and engaged communities | Area of strength |

| 5 Ensures social stability, security and justice | Doing well, but can improve |

| 6 Fosters economic prosperity | Doing well, but can improve |

| 7 Maintains and enhances man-made assets | Area of strength |

| 8 Ensure continuity of critical services | Area of strength |

| 9 Provides reliable communication and mobility | Doing well, but can improve |

| 10 Promotes leadership and effective management | Doing well, but can improve |

| 11 Empowers a broad range of stakeholders | Area of strength |

| 12 Fosters long-term and Integrated planning | Doing well, but can improve |

| Leadership and Strategy | Provides Reliable Communication and Mobility |

|---|---|

| Promotes Leadership and Effective Management | |

| Empowers a Broad Range of Stakeholders | |

| Health and Wellbeing | Fosters Long Term and Integrated Planning |

| Meets Basic Needs | |

| Supports Livelihoods and Employment | |

| Economy and Society | Ensures Public Health Services |

| Promotes Cohesive and Engaged Communities | |

| Ensures Social Stability, Security and Justice | |

| Infrastructure and Environment | Fosters Economic Prosperity |

| Provides and Enhances Natural and Manmade Assets | |

| Ensures Continuity of Critical Services |

Step 2

Citywide engagement

- 18 workshops involving 547 people

- 35 focus groups involving 480 people

- 140 people interviewed on a one-to-one basis

Step 3

Review of city assets and risks

- City assets

- Perceptions

- City risks

- Strengths

Step 4

Data analysis

- Spaces for children to play

- Economic

- Vulnerabilities, cyber, exclusion, inequalities, automation of industry, business start-ups

- Population change

- Poverty

- Children and young people

- Connectivity

- Economic corridor, digital, physical

- Transport

- Cheaper, cleaner, integrated, greener

- Housing

- Climate change

- Extreme weather and air quality

- Segregation

- Housing, education system, division

- Civic pride

- One city, city story

- Cyber threat

- Health

- Dependence on prescription drugs, mental health, nutrition, obesity

- Risk of returning to violence

- Prevalence of cars

- Infrastructure

- Investment and capacity

- City centre

- Retail, housing, dereliction

- UK Exit

- Impact on Belfast

- Financing the city

- City revenue

- Politics

- Leadership, decision making structures

- Fossil fuel dependency

Step 5

Agreed our resilience goal

Transition Belfast to an inclusive, net zero-emissions, climate resilient economy in a generation.

Step 6

Identified multiple problem solvers

These shocks and stresses make the city more vulnerable and could weaken our capacity to resist and recover from future challenges.

- Climate adaptation and mitigation

- Participation of children and young people

- Connected, net zero-emissions economy

Step 7

Citywide consultation on a draft strategy

Direct engagement with 1,223 people through our consultation partnership with Urban Scale Interventions and receipt of more than 80 written responses.

Case Study in Urban Resilience

Fire at Bank Buildings, August 2018

Belfast experienced an acute shock in 2018 when a culturally historic building, known as Bank Buildings which housed Primark, a global retail chain, was severely damaged by a fire that started on 28 August 2018 and continued to burn for three days. Located right in the heart of the city centre on a major junction, the fire tested multiple aspects of the city’s resilience.

One hundred firefighters successfully prevented the fire from spreading to nearby businesses, shops and restaurants, and no one was killed or injured. However, a significant proportion of the building’s internal structure was burnt away, either collapsed or was severely damaged with the external facades subject to further damage. In the immediate weeks following the fire, the building’s physical fabric remained very vulnerable and posed a threat to public health and safety.

On engineering advice, a safety cordon was established to protect the public. While the cordon closed 22 business in close proximity, the impact was felt much further across the city centre. The cordon effectively created four cul-de-sacs in the heart of the central retail district in which footfall significantly reduced. Anecdotal evidence from local traders reported decreases in sales levels between 20 per cent and 70 per cent amongst the hardest hit areas. There was considerable concern that the continuation of the situation would lead to fundamental long-term changes in consumer habits within the city centre.

Pedestrians, buses and vehicles had to be rerouted in response to the cordon. This significantly added to the impact on footfall, and to pressures already being felt by the retail sector during a challenging year. The cordon acted as a barrier and restricted pedestrian and vehicular access through Castle Place junction, and as a result pedestrians were required to undertake significant diversions using alternative, longer routes to navigate the city centre. In addition, buses were unable to penetrate into the centre of the city and were subject to significant delays and revised timetabling.

The building was a Category B1 Listed Building located within the city centre conservation area. Immense in size, it was within metres of other buildings close by. Major challenges existed for the owner to assess the damage to the building and make decisions regarding the building’s future. In late October, Primark successfully applied to Belfast City Council for listed building consent to take down, record and assess for restoration purposes the uppermost parts of the building. By the following April, a series of ballast-filled shipping containers had been erected around the building to enable the commencement of a long-term restoration project.

For Belfast City Council, the immediate primary concern from the beginning was the safety of people in the city, and to reduce as much as possible the impact on businesses and trade. It established a City Recovery Group made up of partners across the city to coordinate the city’s recovery efforts. It held clinics with businesses directly affected, and held ongoing conversations with businesses through the Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) in the city. A #YourBelfast media campaign in the immediate weeks following the fire aimed to remind people that Belfast was open for business.

A ‘Rewards App’ was developed to encourage people to spend in the local area and a ‘yellow dot’ trail guided pedestrians around the cordon to sustain footfall in the city. A major revitalization programme was undertaken to ‘light up’ the city at Christmas via a series of installations to encourage people to spend time in the city. A combination of cultural events and playful installations, dressing up city streets impacted by pedestrianisation worked in combination to give the city centre an energized feel in the busy retail period.

In the New Year, the ongoing pedestrianisation of the area was taken as an opportunity to provide a pop-up play park for children, with seating areas, planters and art to help make the area attractive.

Conclusion

A fire in a building of its size and central proximity amounted to a major shock for the city. It posed significant challenges to the city’s resilience. It tested the city’s economic resilience and emphasised the importance of strong and supportive citywide networks. It prompted a debate on the role of heritage in the city. Poignantly, the sight of a burnt-out building in the city centre reminded many people of a time when Belfast experienced regular security alerts and fires. It highlighted the city’s exposure to retail risks, and reminded decision makers in the city of the importance of an ‘experience economy’ and how critical it is that we build a vibrant city centre where people work, live and play. Perhaps most tellingly of all, the sight of children playing in a pop-up park next to the Bank Buildings appeared to inspire the public of the importance of play in the city. The park’s removal, following the reduction of the cordon has prompted important debate about the importance of play in our city.

Shocks and Stresses for Belfast: 2020

This strategy does not attempt to comprise a final comprehensive list of all the risks that Belfast faces. Like other global cities, it represents the starting point to build our resilience and will be updated to reflect new challenges and opportunities.

What is a shock?

A shock is a sudden, sharp event that can immediately disrupt a city.

What is a stress?

A stress is a slowly moving phenomenon that weakens the fabric of a city.

Shocks

- Infrastructure capacity

- Public health

- Cyber resilience

- Condition of existing housing stock

- Flooding and extreme weather events

- UK Exit from the EU

Stresses

- Economic recovery capacity

- Climate change

- Mental ill-health

- Poverty and inequality

- Housing supply in the city

- Use of prescription drugs

- Population change

- Segregation and division

- Governance and financing of risk

- Carbon intensive systems

Infrastructure capacity

The issue of the city’s infrastructure emerged as a major theme in the workshops, focus groups and data analysis undertaken to develop this strategy. Existing infrastructure has been adversely impacted by a period of underinvestment, which is having a negative impact on the city’s economic and climate resilience.

In October 2020, an independent Ministerial Advisory Panel on Infrastructure produced a report which summarised the views of over 100 individuals and organisations on current infrastructure planning and delivery in Northern Ireland. The conclusions strongly mirror those expressed in the development of this document:

- Strategic infrastructure projects frequently suffer time delay and cost overruns.

- Over-reliance on the Barnett funding allocation to fund our public infrastructure is stifling growth and innovation.

- Crucial parts of our infrastructure are at a critical point and there is clear evidence that this is having a negative impact on other major investment decisions.

- We struggle to see beyond our political and financial timeframes which, by their nature, are too short term for effective infrastructure planning.

- Our neighbours on these islands have ambitious infrastructure plans for the next 20-30 years.

- Lack of longer-term planning and appropriate market management often results in legal challenges which cause major delays.

- The population of NI is projected to increase by 8 per cent by 2041, with the 65+ age brackets increasing to 25 per cent of the population. There is little evidence that we are planning sufficiently for this demographic change. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA).

- The current system operates in silos with limited cooperation between central and local government, and with the private sector.

- There is a general failure to identify potential synergies to collaborate or secure economies of scale by working more closely together within NI, or with other bodies outside NI facing up to these very same challenges.

- We are lagging behind in terms of our environmental performance, and urgently need a step change to address climate change and meet our ambitions in respect of the wider UK 2050 net zero targets.

- There is a regional imbalance and urban-rural divide in terms of infrastructure provision. This needs to be addressed to ensure inclusive growth and to improve the quality of life and wellbeing for everyone in NI.

- External factors such as COVID-19, Climate Change and Brexit are dramatically impacting the economic landscape of NI (and will continue to do so for years to come); we must ensure we are nimble, able to capitalise on the growth opportunities that will arise.

To inform the development of this strategy, our strategic partner ARUP undertook a high level assessment of the city’s assets.

The study identified key areas for intervention to improve infrastructure provision within the local authority area, and these findings were borne out in our consultation and engagement sessions with stakeholders:

- The importance of enhanced connectivity across the River Lagan through a series of bridges.

- The need for extended public transport network, particularly through BRT Phase 2 and improved walking and cycling networks.

- Significant pressure on drainage and wastewater infrastructure’ in the city and implications for the city’s economy.

- Targeted enhanced digital connectivity, particularly in locations of target growth sector investments.

Separately, Belfast City Council commissioned the Belfast Infrastructure Study to identify the range of infrastructure challenges in the city. The outcome of the study will continue to inform this strategy, both in terms of future versions and implementation. This strategy has also been informed by a number of relevant reports from the National Infrastructure Commission which advises the UK government; and reports from the UK Committee on Climate Change, on the risks associated with a range of climate scenarios for NI infrastructure.

It should also be noted that the ‘New Decade, New Approach’ document recognises several infrastructure classes requiring intervention, and commits to prioritised investment. The Ministerial Advisory Panel on Infrastructure recommended to the Minister the establishment of an independent Infrastructure Commission for Northern Ireland. Properly established and resourced, such a Commission would resolve many of the issues associated with infrastructure planning and delivery in the city, and across the region.

Drainage Infrastructure Capacity

A fit for purpose wastewater and drainage system is a critical asset to any city. It mitigates the effects of flooding, enables climate resilience and contributes to public health and the economy.

Connection to drainage and wastewater infrastructure is a condition of planning consent for development and therefore underpins sustainable economic development in every city. Furthermore, the capacity of a city’s drainage system has a direct impact on prevalence of flooding. Put simply, a fit-for-purpose drainage and wastewater system with sustainable levels of investment is critical for a city’s economic, social and climate resilience.

Significant investment has been necessary for several years to improve the drainage and wastewater assets that serve Belfast. In 2015, the Living with Water Programme Board was initiated to develop a Strategic Drainage Infrastructure Plan for Belfast. This aims to provide integrated sustainable solutions which will alleviate the risk of flooding, enhance the living environment and sustain economic growth. The board, which operates as a collaboration between organisations, has been working to set out:

- The scale of flood risk to Belfast.

- The deterioration of Belfast Lough’s water quality due to pollution from diffused sources, including agriculture, and from sewerage system overflows and wastewater treatment works discharges.

- The scale of investment needed.

- The potential wider benefits of the proposed approach to investment planning.

Belfast’s wastewater treatment system faces a number of significant issues, which could impact on the city’s resilience - in particular its ability to adapt to, and mitigate climate change. Capacity risks can also impact on economic resilience, given the relationship between infrastructure and the health of the economy.

Northern Ireland Water publishes information on wastewater systems which are operating at or near capacity. Its August 2019 online report stated that Belfast wastewater treatment works is predicted to reach capacity in 2021. Furthermore, it reported that ‘In addition to the wastewater treatment works, wastewater network capacity issues are emerging due to sewer network modelling activities being undertaken at Belfast (Glenmachan sub catchment), Kinnegar (Sydenham sub catchment), Newtownbreda, Whitehouse, Dunmurry. As a result of this, new connections are being declined in parts of the catchment.’ The issue was further emphasised by the Chair of Northern Ireland Water in the company’s 2018/19 Annual Report which referred to the potential adverse impact of underfunding for economic development across NI.

The ‘New Decade, New Approach’ document also recognises that wastewater infrastructure is at or nearing capacity in many places in NI.

The capacity issues identified above represent a substantial risk to the city’s resilience. Out of sewer flooding, inadequate capacity of the existing system and treatment works with inadequate storm storage capacity all present challenges to the operation of the city and could inhibit the scale and nature of future development, at a time when housebuilding at scale is required. These risks are heightened over time as the system continues to deteriorate and as our climate changes.

On 11 November 2020, ‘Living With Water in Belfast’ was published for consultation, a 12 year, £1.4 billion investment plan for drainage and wastewater management in Greater Belfast. Implementation of the plan in the coming years would significantly alleviate a key resilience challenge for the city.

How a resilient city values water

Belfast currently has ready access to a plentiful supply of drinking water. However, all cities building their climate resilience should be aware of the potential for water shortages. The Climate Change Risk Assessment for Northern Ireland has identified the potential risks to humans and to agriculture and wildlife from drought. These factors, combined with the lack of capacity in our wastewater treatment system, suggests a strong case for a city-wide focus on valuing our water supply and on water conservation.

Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS)

Infrastructure integrated into urban places which provide a drainage function, are widely recognised as playing a crucial role in ensuring water resilience at a city-level. The Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Strategy is a helpful document in setting out guidance for city partners to drive a proactive approach to SuDS. At the time of writing, the Department for Infrastructure is finalising a substantial set of proposals for sustainable drainage across the city. Investment in sustainable drainage of this kind, over this decade, is essential to meeting the city’s climate ambitions and boosting its resilience.

Conclusion

Belfast is one of hundreds of cities globally that face the competing challenges of driving sustainable economic development and population growth, delivering city centre densification while preparing for a changing climate and rapid decarbonisation. The UK National Infrastructure Commission has rightly recognised these significant challenges, as have global institutions such as the World Bank and the World Economic Forum. Infrastructure is increasingly understood as a key growth driver in cities. This can sometimes result in perceived tensions between infrastructure planning and economic growth strategy. It should not be the case. Competitive, resilient cities have shown that sustainable and inclusive economic growth is possible when infrastructure planning enables growth. Lack of infrastructure capacity should not hinder or dictate economic strategy - to do so would expose a city to a range of risks, and ultimately weaken its resilience. On this basis, investment in Belfast’s infrastructure capacity will be a major determinant of the city’s resilience, and its capacity to transition to a low carbon economy. This will require reconsideration of how infrastructure is funded in the future. It is almost certain to necessitate new funding models to better plan for growth capacity and climate resilience in the coming years.

Condition of existing Housing Stock

Conditions in existing NIHE social housing

The Northern Ireland Housing Executive (NIHE) is the strategic housing authority for NI and its housing stock in Belfast numbers almost 26,000 units. Investment in, and maintenance of existing stock is a core priority for any landlord, however it has wider impacts for the city. A well maintained social housing stock ensures the long-term health and wellbeing of its population. It enhances social capital and if well planned, can have a significant positive impact on reduction of carbon emissions in a city.

“Well maintained social housing stock ensures the long-term health and wellbeing of its population.”

Northern Ireland Housing Executive stock in Belfast has traditionally benefited from significant ongoing investment, and therefore until relatively recently has been able to maintain its stock condition. However, a number of studies have recently shown that the condition of NIHE stock has deteriorated, arguably to a point where it represents a risk to the wider city.

In 2014, the then Department for Social Development and the NIHE jointly commissioned Savills to undertake an Asset Commission to understand the scale and nature of investment required in the NIHE stock. Savills carried out a comprehensive exercise to assess the current and future repairs and maintenance liabilities of NIHE’s properties and related assets. Savills found:

- The stock has deteriorated during the last 5 years… projections of costs moving forward have therefore increased and will continue to do so without sufficient investment.

- Just under 44 per cent of the stock (37,974 units) is in asset groups with an average net present value (“NPV”) per unit which is negative [i.e. the rental income collected from these properties is not sufficient to maintain the properties and service residents over the next 30 years]’.

- The total cost at today’s prices [of the investment required in the NIHE stock] is £6.7bn.

- There is significant investment [circa £1.5bn] required during the next 5 years. In addition to the financial challenge this presents, there is also a significant practical challenge in terms of the capacity of the market to deliver such a large programme...a 3-year lead in time is likely to be required before the levels of investment identified can be delivered on the ground and current investment programmes are concluded’. This “delay” will result in an increase in liability [from £1.5bn] in the 5 years that follow...’.

Worryingly, the 2014 report predicted that ‘The situation has worsened since 2009, and is likely to worsen again in the next five years in the absence of increased investment (made at the right time in the right place) combined with the application of modern asset management principles.’

Six years on, it appears that these warnings were prescient - the step change required to improve stock conditions has not occurred, so much so that the NIHE has publicly acknowledged that it may have to de-invest in homes. This would amount to a significant and adverse challenge to the city of Belfast, which requires a continual and ongoing supply of good quality social housing to meet its social and economic needs. Furthermore, the current condition of NIHE properties could make decarbonisation a much more significant challenge for the city.

A recent statement by the Minister for Communities acknowledged the scale of investment needed, and that two years have passed since the previous analysis of the scale of the investment challenge.

In her words, ‘the current situation is most certainly worse and the scale of the investment even greater. New investment requirements have materialised since 2018: the consequence of the Grenfell Tower disaster and the ambition to reach a position of carbon neutralisation in our homes by 2050.’ In response, the Minister has announced her intention to change the status of the NIHE to enable it to borrow to fund investment, and with proposals to come forward in 2021/22.

Housing conditions and health outcomes

Housing conditions have a profound impact on health outcomes. Belfast’s aging population, the condition of its housing stock - across all tenures, and projected patterns of extreme weather (warmer summers and colder, wetter winters) present key health challenges across the city. Older people and those with chronic health conditions are more at risk from cold weather and tend to live in greater fuel poverty. A sustained, collaborative and targeted approach is necessary.

The Health and Social Care Board is leading the Belfast Warm and Well Initiative, bringing together partners to take an evidence based approach to prevention, risk identification, data sharing, service coordination training. However, a strategic approach to improving energy efficiency and housing conditions, e.g. ensuring high standards of ventilation and insulation across all tenures in the city is also necessary in this decade, to avoid exacerbating existing health conditions and prevent avoidable deaths each year.

Housing conditions in the private sector

Poor housing conditions, and in particular energy inefficient housing, exist across all tenures and can fundamentally impact health and wellbeing of residents, as well as wider society goals. Importantly, the UK Climate Change Committee has referred to UK homes as ‘not fit for the future’ given their levels of energy inefficiency. Health research has proven the negative impact that poor housing conditions can have on health particularly for those with underlying conditions. Belfast’s housing stock - particularly in the private rented sector- requires retrofit and modernisation to eradicate fuel poverty and meet the city’s climate ambitions. Future legislative change is required to set a target on energy efficiency of our buildings, and implementation ‘Belfast’s Net-Zero Carbon Roadmap’ will be a critical driver towards these ambitions. The Northern Ireland Executive’s future economic strategy – which will require a jobs-led approach to growth will be a critical lever. Belfast’s Innovation and Inclusive Growth Commission has produced a ‘thinkpiece’ recommending investment, at scale, in community based retrofit programmes, to improve the energy efficiency of homes, reduce fuel poverty and sustain local employment. This strategy has continually stressed the integration of climate and economic strategy to meet the city’s Belfast Agenda priorities- retrofitting of homes is an excellent opportunity to achieve several outcomes at once.

Conclusion

The Northern Ireland Housing Executive has commented publicly on the risks associated with its investment requirements - and the need for £3bn of investment across its entire stock in the next five years. The consequences of not meeting these requirements could include de-investment in homes. The implications of de-investment in social housing at a time of existing housing stress, income deprivation and climate related challenges represent a significant and urgent risk to the city.

Public health

Belfast’s experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, which first affected the city’s residents during the public consultation on the strategy, has given a unique insight into the city’s systemic vulnerabilities. While pandemics were not previously identified as a likely shock to the city, community planning partners had noted global research (World Economic Forum, 2019) which found that environmental degradation across the world makes viral pandemics more likely in future.

At the time of writing, there remains a substantial public health risk, and therefore we are far from understanding the long-term social, economic and environmental impacts of COVID-19 for Belfast.

Nevertheless, the pandemic has reminded cities such as Belfast of two important principles; firstly, that good health is a central element of a city’s resilience to shocks and stresses of all kinds, and secondly, that cities must take a number of steps to be resilient to public health crises. We have taken account of both of these lessons, and improved the strategy on this basis.

Evidence from Belfast suggests a number of key characteristics that are important to note, when considering the health of the population, and its resilience to shocks and stresses:

Health inequalities remain a significant concern

The Department of Health’s ‘Health Inequalities Annual Report 2020’ highlighted that Belfast’s health outcomes were worse than the NI average in 32 out of 41 outcomes measured; most notably in relation to male life expectancy, drug related mortality and alcohol specific mortality.

- Male life expectancy in Belfast’s most deprived areas is 71.7 years; 4.6 years less than the Belfast average (76.3 years). Female life expectancy is 3.6 years less than the average (81.1 years).

- Inequality gaps for suicide remain persistently high with the rate in the most deprived areas of Belfast around two-thirds higher than the Belfast average.

- However, the 2020 report identified a narrowing of inequality gaps in 15 of the 40 outcomes assessed.

Demographic change must be a key feature of health planning for the city

- Belfast was the first Age Friendly City in Northern Ireland and has a reputation as a leader in healthy ageing beyond the UK. This strongly contributes to the resilience of the city. Active Ageing with employment for older groups and opportunities for physical activity and reduced social isolation supported by inclusive transport infrastructure, walkability, green areas will help make an ageing population a positive asset for the city rather than a challenge to its resources. The number of people with dementia will also increase significantly and the work being led by community organisations to develop Dementia Friendly Neighbourhoods will contribute significantly to its resilience by ensuring that those with dementia and their carers have ready access to all the social assets within their communities who understand their needs.

- As set out in the section on ‘population change’, Belfast’s population is ageing. The number aged over 65 will increase by one third with over 20,000 more people in this age group by 2041 (NISRA). People aged 45 now will be over 65 in 2041 requiring a focus on their health as well as those who are older now.

The relationship between housing, transport and infrastructure policy and health outcomes is critical to the city’s resilience

- The resilience of the city, as demonstrated during the pandemic, depends on having resilient local neighbourhoods where leadership has been evident. Evidence is also emerging globally of the importance of integration of housing, transport and infrastructure services to build greater resilience into the design of resilient neighbourhoods. Such neighbourhoods should be well-connected with walkable or cycle-friendly routes throughout, with a mix of inter-generational, cross-tenure housing, with a layout offering shared space to create a sense of safety and belonging as well as good relations and social inclusiveness. Lessons should be learned from cities such as Melbourne with its ‘15 minute neighbourhoods’ and Paris and its 15 minute city.

- The Strategy recognises mental health as a systemic stressor in the city which can be amplified if crises are not well-managed. The pandemic is likely to see a sharp rise in mild to moderate conditions arising from social isolation and loneliness as well as economic recession. Isolation and loneliness is recognised as a significant public health issue, affecting as many as 1 in 10 adults. The creation of socially inclusive neighbourhoods through support for social assets and creative physical planning, building on the upsurge of interest in volunteering in response to the pandemic could reduce demand for more specialist services.

Conclusion

Belfast’s future resilience to shocks and stresses will depend on the underlying health of its people. This therefore requires a singular focus on ensuring the population is as active and healthy as possible. Opportunities should be proactively considered, through the Community Planning Partnership structures to ensure that housing, health and infrastructure delivery can contribute to, and demonstrate positive health outcomes at a local level.

“The strategy will put the city in a much better position to meet critical threats to the health of our citizens and protect the most vulnerable.”

Iain Deboys,

Assistant Director for Contracting and ECRs and Commissioning Lead, Health and Social Care Board, Belfast

Flooding and extreme weather events

To be a resilient city, Belfast must be able to withstand the impact of flooding and extreme weather events.

The effect of climate change will be profound and with ongoing risk management and risk assessment, Belfast will be resilient in understanding potential impacts, infrastructure preparedness and economic consequences.

Sea level rise

| City | Range in low emission scenario (shown in cm) |

Range in high emission scenario (shown in cm) |

|---|---|---|

| Belfast | 11 to 52 | 33 to 94 |

| Cardiff | 27 to 68 | 51 to 113 |

| Edinburgh | 8 to 49 | 30 to 94 |

| London | 29 to 70 | 53 to 114 |

Changes to our weather

Climate change is causing many extreme weather events to become more intense and frequent, such as heat waves, droughts, and floods. In the summer of 2020, wildfires caused fire fighters to be called to numerous incidences that impacted residents of north Belfast. The image shows the trend in temperatures in NI since 1910. Cities are already responding to the financial impact of extreme weather events. The Glasgow City Region has estimated that the cost of four typical weather events between 2012 and 2017 cost the city region £44.5m.

NI mean temperatures

| Year | Temp (celsius) |

|---|---|

| 1910 | 8.2 |

| 1920 | 8.4 |

| 1930 | 8.5 |

| 1940 | 8.8 |

| 1950 | 8.7 |

| 1960 | 8.3 |

| 1970 | 8.5 |

| 1980 | 8.5 |

| 1990 | 9.0 |

| 2000 | 9.3 |

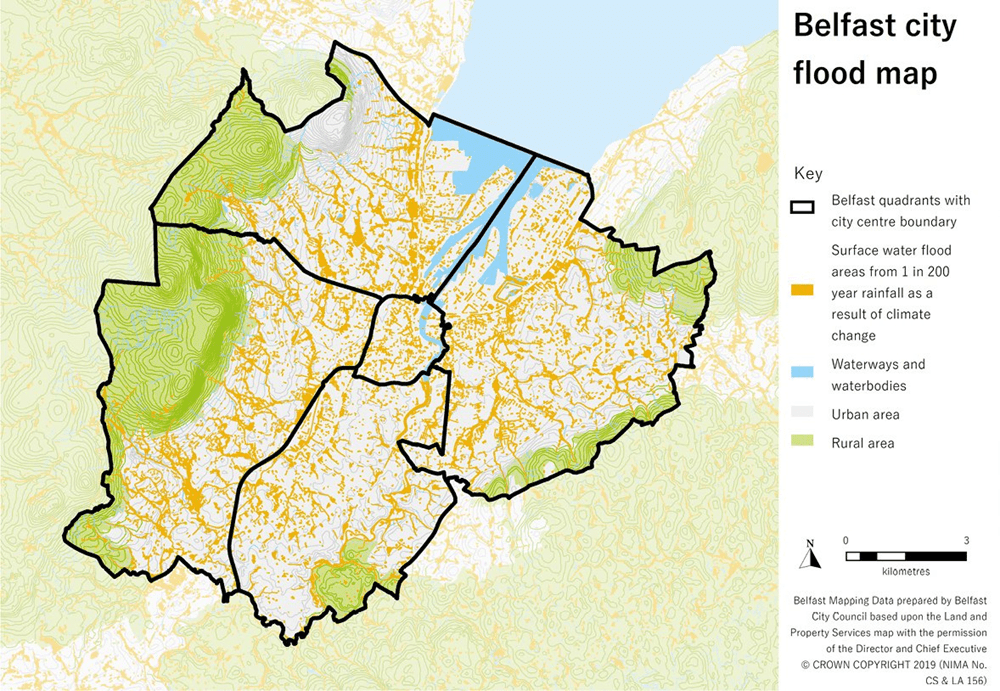

Flood risk in Belfast

Belfast is located within the River Lagan catchment and at the mouth of Belfast Lough. It is a city with very close proximity to water, and where water resilience is critical to the operation of the city. Belfast makes up a large proportion of the geographical area estimated to be at “Significant risk of flooding in NI.” The Northern Ireland Flood Risk Assessment (2018) is a critical source, and identifies Belfast as one of twelve Areas of Potential Significant Flood Risk (APSFR) in Northern Ireland. Several tributary rivers flow from the hills surrounding Belfast, into the city to the River Lagan and Belfast Lough, all of which have the potential to flood during periods of heavy prolonged rainfall. Belfast is therefore at risk of flooding from a number of sources including tidal (the sea), fluvial (rivers) and surface water (pluvial) unable to drain away quickly into the combined storm and combined sewerage network, much of which was built in the late 19th and early 20th century. The fact that Belfast has a mainly combined sewer network means there is additional pressure on the system every time the city experiences heavy downfalls. As the city grows, additional pressure on the capacity of the network could increase the risk of flooding. Belfast has a history of flood events and major damages are caused by both fluvial and pluvial events. The five highest tidal surges have been recorded since 1994, most recently in early January 2014. “The economic consequences of flooding for the city are well-known.“

“The NI Flood Risk Assessment (2018) predicts that the city is the most economically impacted of all areas of risk in Northern Ireland with Aggregated Annual Average Damages (AAADs) of approximately £16m.“

Coastal and pluvial flood risks are both sensitive to climate change. The impact of climate change causing sea level rise will increase the number of properties at risk of tidal flooding in the city to over 3,400 (2,640 Residential and 770 Commercial) by 2065 and over 7,900 (6,050 Residential and 1,860 Commercial) by 2115.

The Belfast Tidal Flood Alleviation Scheme is a landmark project that will provide a long term approach to tidal flood risk management for Belfast. Much of the city centre is between 1m to 2m below extreme tide levels, so a weather event of magnitude would cause serious disruption to the local economy, the transport network, and the social fabric of the city.

To understand the risks associated with climate change, ARUP undertook a high-level risk assessment of existing city infrastructure. The study looked to three points in the future (2040, 2060 and 2080) for four key climate hazards: sea level rise, extreme heat, drought and extreme cold. The two key hazards with the biggest projected impact for Belfast are (1) sea level rise and flooding and (2) extreme heat. ARUP found that many assets in the city are already at risk of flooding which is projected to be exacerbated by sea level rise and an increase in winter rainfall. The planned new flood defences will provide some protection but residual risk is projected to remain.

Belfast city flood map

Conclusion

The forthcoming tidal flood alleviation scheme provides a mitigation against worsening flood levels in the future, therefore it is expected to provide some improvement to the city’s overall climate resilience. However, there remains significant work ahead to ensure the city’s existing infrastructure is climate resilient. Sea level rises and flood risk, coupled with extreme heat will have significant implications for the city’s infrastructure, as with many other cities. Evidence from cities globally has demonstrated the negative impact this can have on the local economy, the transport network and the social fabric of a city. Belfast must therefore carefully plan the future of its infrastructure to ensure climate resilience is prioritised.

Cyber resilience

A resilient city is reliant on its digital infrastructure, data and associated cyber security. As cities increase their digital dependency, their exposure to attack grows. A resilient Belfast will be able to deliver its essential services in the event of any breach.

As Belfast grows, and becomes increasingly reliant on a digital eco-system to achieve its ambitions, its ability to mitigate and manage data and cyber security risks will be essential. Experience from other cities with a sophisticated data infrastructure shows that as cities increase their digital dependency, their exposure to attacks also grows (McKinsey, 2018). A Smart Belfast must therefore be a secure and resilient Belfast. Being a cyber-resilient city means more than just being secure - it means being capable of delivering essential services in the event of a breach.

A security breach has the potential to disrupt the city; however, cyber-crime has increasingly affected communities and individual households too. Cybercrime knows no borders and while authorities have experienced increasing levels of sophistication in mode of attack in recent years, low-level basic opportunistic attacks remain prevalent.

“Being a cyber-resilient city means more than just being secure - it means being capable of delivering essential services in the event of a breach.“

A significant cyber incident can affect the functions of the city - organisations and the public need to consider the impact which a major incident will have, what measures are needed and how to recover. Cyber security planning should be part of routine risk management and should be embedded in the structures and objectives of every organisation and business.

The National Cyber Security Centre, which is part of GCHQ, is a well-established source of information regarding escalating volumes and types of threat. While this is extremely valuable at a national level, at a city level more work is required to develop more cross-sector plans to future proof our digital environment.

Development of digital infrastructure and connectivity

Secure digital infrastructure is critical to the fabric of any modern city- to support its social and economic goals. In recent years, Belfast has improved its digital connectedness - however it must retain this advantage through (1) a strategic approach to the development of a smart/digital city (2) sustained investment in the growth of its digital infrastructure (3) significant focus on the security and resilience of our digital infrastructure assets.

A number of key reports have recently made a similar case. Matrix, the Northern Ireland Science Industry Panel, formed a sub panel of experts in the Digital ICT sector to look at the opportunities within the sector and produce a capability assessment and foresight study into NI’s Digital Information and Communications Technology sector. Its 2016 report made a number of significant recommendations that - while focused at a NI level - remain highly relevant to driving Belfast’s economic resilience:

- Develop and deliver a coordinated Digital Strategy to bring together the key stakeholders and initiatives required to transform NI into a fully digitized and Smart society and appoint a Chief Digital Officer to build a digital society.

- Develop a 3-5-10 year Skills Investment Plan for the Digital ICT sector.

- Ensure that NI has an exemplar digital infrastructure within and between urban areas to secure NI as an exemplar smart, connected region.

- Provide an integrated, agile platform, based on open standards which expose appropriate data and service APIs to nurture the development of an innovative ecosystem.

- Ensure that the cyber security sector is supported and developed.

Belfast is well placed to build its cyber resilience, in part due to the development of cyber security expertise in the city. CSIT, the Centre for Secure Information Technologies at Queen’s University is recognised for its world class research, and its work to enable new value and venture creation and ensure an entrepreneurial approach in the area of cyber security. It facilitates ‘NI Cyber’ a cluster of companies based in NI that are developing world-leading cyber security technologies for customers worldwide.

Belfast City Council has prioritised a ‘smart cities’ approach to digitising and connecting the city, to achieve its economic and social ambitious, and in turn contributing to the city’s resilience. Smart Belfast brings together our universities, businesses, local government and citizens to collaborate, innovate and experiment using cutting-edge technologies and data science. The Matrix report was instrumental in informing the Belfast Region City Deal Innovation and Digital Pillar, which will deliver a number of its recommendations at a city-region level.

- The Regional Innovators Network (RIN) will create a unified environment in which the districts across the Belfast City Region are able to work together to develop and deliver a response to the regional needs for spaces within which entrepreneurs and SMEs can develop new products and services, and work with the larger businesses in the region.

- The Infrastructure Enabling Fund (IEF) will support the deployment of advanced and resilient connectivity infrastructure across the Belfast region.

- The Smart District and Regional Testbed Network consists of key locations across the Belfast region that will act as hubs for development of advanced digital and physical infrastructure and will foster early adoption of new digital products and services at large scale.

- The Digital Innovation Platform and Partnership (DIPP) is a shared physical and digital environment where academic research community, tech entrepreneurs and industrial partners will come together to address key challenges in business and society through the application of the Internet of Things (IoT) and data science.

Consumer protection on cyber security is also critical to cities, like Belfast, that are becoming increasingly digitally connected. The Department for Culture, Media and Sport has produced helpful guidelines for Consumer IoT security that aim to strengthen the security of consumer smart devices sold in the UK and define the security requirements for the Internet of Things (IoT). These standards will allow configured devices for Smart City initiatives to be better protected.

Belfast Region City Deal is a ‘once in an generation’ opportunity to build Belfast’s resilience by increasing its digital connectivity.

The Infrastructure Enabling Fund (IEF) will:

- Support the deployment of advanced and resilient connectivity infrastructure across the Belfast Region.

- Catalyse digital innovation towards increased productivity and inclusive economic growth.

- Manage the deployment of advanced wireless and fibre network infrastructure over the lifetime of the City Deal comprising of 4G LTE, Wi-Fi, IoT, optical and 5G technologies.

- Develop next-generation infrastructure to support the provision of a range of connectivity services, and will be critical for businesses within the Belfast region to catalyse their growth by having access to the latest communication technologies.

- Provide high value sectors in the city region with the digital infrastructure needed to test the application of new and emerging digital technology and solutions. This will provide a significant boost to our economic resilience. Critically, the Digital and Innovation Pillar of the City Deal will be implemented in an integrated way- to ensure that the outputs and outcomes arising from the City Deal are directed and driving inclusive economic growth in the City Region. However, it places even greater emphasis on the importance of secure and resilient infrastructure.

Conclusion

There is no single coordinating body for the identification and management of cyber risk at a city level. While some individual organisations have developed cyber resilience plans to varying degrees of sophistication, this remains ad hoc, and with very little support for small organisations, and little focus on business continuity following a potential cyber or digital attack. Furthermore, there has been no single published account of the potential cost implications of a cyber-security threat to the city.

Protecting the city from cyber threats should be considered the collective responsibility of senior leaders across the city. This strategy advocates closer working relationships across organisations in Belfast- with academia and the private sector - sharing threat information and good practice and collaborating to make it more difficult for cyber threats to succeed.

Belfast’s objectives to ensure cyber and digital resilience should be:

- To make Belfast unattractive to cyber criminals - through resilience and recovery.

- To build an eco-system of supported city partners.

- To build a pipeline of skills and education.

UK exit from EU

On 31 January 2020 the United Kingdom left the European Union and the Withdrawal Agreement concluded with the EU became law. The ‘transition period’, provided for in the Withdrawal Agreement, comes to an end in December 2020. At the time of writing (October 2020), trade negotiations to establish the UK’s future trading relationship with the EU remain ongoing. These negotiations on the UK’s trading relationship will have enormous implications for Belfast’s economy and for the wider region.

A number of studies have been undertaken to assess the future impact of UK Exit on NI, however there is no published central government assessment of the potential impacts of UK Exit for the city of Belfast or for similar UK cities. Earlier this year, a previously confidential study undertaken by the UK government detailing 142 areas of life in NI that will be impacted by Brexit was published by the House of Commons Exiting the EU Select Committee. The document is instructive in outlining the range of policy and practice areas - beyond trade and customs checks - that would be affected by a managed UK Exit. Furthermore, it highlights the scale and nature of formal and informal cooperation between the two jurisdictions on the island of Ireland, some of which may be impacted by a managed exit, and some adversely impacted by an unmanaged exit (i.e. departure without a deal).

It is extremely likely that unsuccessful trade negotiations between the UK and the EU would represent both a short-term shock to the city of Belfast, and have longer term implications for the operation of the economy.

Conclusion

The UK’s decision to leave the EU has long term implications for the city of Belfast. Significant re-framing of our relationship with cities in Europe is required; work to sustain levels of investment in a new trading landscape will also take time; and its funding relationships with key EU bodies requires careful planning into the future. For these reasons, UK Exit from the EU will remain a significant area of focus and of risk management for the city.

Economic recovery capacity

Economic resilience refers to a city’s resistance to and recovery from an economic shock. Improving resilience therefore includes a focus on the vulnerabilities that either make an economic shock more likely, or that exacerbate a crisis.

Following the global financial crash (2008-09), policy makers began to pay greater attention to the cost of crisis in a city- sometimes referred to as ‘GDP at Risk’, which can profoundly damage long-term economic development. The OECD, for example, has developed a set of indicators to help cities help policy makers detect vulnerabilities early on and monitor country specific risks. Like several other cities, Belfast has made economic resilience a core priority, committing the city in the Belfast Agenda to take a targeted approach to addressing those issues which pose the greatest risk to the city and its economy.

As a city with important economic relationships globally, Belfast is susceptible to global economic trends and headwinds. Our focus on economic resilience seeks to ensure (1) strong resistance - when economic shocks happen, we are prepared and can ensure the shock has a temporary impact; and (2) have with greater capacity to adapt and recover, and to maintain progress towards our inclusive growth ambitions.

Resilience to what?

The World Economic Forum Global Risks Report is a credible and often cited source of information on immediate and longer term risks faced by cities and states globally. Published annually, it allows for tracking of risks over time.

In 2020, its report identified immediate risks emerging globally; a ‘synchronised economic slowdown’, continued warmer temperatures globally, expected increases in cyberattacks, and growth in protests around the world against systems that exacerbate inequality. The report was published in January 2020, as COVID-19 was confined to a small number of countries and had not yet been declared a ‘pandemic’.

Since early 2020, global economic forecasts have worsened, and in the UK economic forecasts suggest a prolonged shock as a result of the pandemic. At the time of writing (October 2020) the Bank of England has warned of an ‘unusually uncertain’ outlook. HM Treasury comparison of independent forecasts predicts an average GDP drop of 10 per cent for 2020, an average unemployment rate of 7.3 per cent for 2020, and average public sector net borrowing for 20202/21 to sit at £343bn.

An unsettled world, global risks and Belfast

For the first time in the history of the WEF Global Risks Perception Survey, environmental concerns dominate the top long-term risks globally. These risks are set against a worsening macro-economic outlook, which has been emerging for some time, i.e. before the impact of COVID-19. The 2020 report makes a number of observations that are relevant to Belfast; risks to economic stability and social cohesion, climate change and accelerated biodiversity loss, consequences of digital fragmentation, and health systems under pressure.

For Belfast, proactively managing the impact of these global risks locally is challenging, but essential. The impacts for Belfast could be:

- A potential slow-down of growth in investment and Foreign Direct Investment in the city, if property funds look outside of the UK due to uncertainties arising from the impact of UK Exit from the EU.

- Increased costs for businesses and potential major shocks for industry depending on the nature of the UK’s future trading relationship with the EU, and particular arrangements for NI.

- Supply chain shocks - in particular costs associated with accessing supplies depending on the nature of the UK withdrawal from the EU.

- Currency volatility and its impact on exports.

- Economic shock arising from COVID-19, followed by a prolonged global slow down could choke off the slow recovery being experienced by the city since the financial crash.

- Slowdown in scale of transition to low carbon technologies thereby reducing potential to take advantage of opportunities to be gained.

As a city with significant exposure to the impact of the UK’s exit from the European Union, and with underlying existing economic vulnerabilities, Belfast must prioritise how it builds resistance to economic risks, as quickly as possible.

This strategy and the establishment of an Innovation and Inclusive Growth Commission is aimed at institutionalising an approach to managing long term economic risks thus boosting the city’s economic resilience.

Belfast’s existing economic resilience

In 2018, the UK Core Cities Network commissioned Cambridge Econometrics to investigate the economic resilience of cities. In preparing this strategy, through our membership of the Core Cities network, we supplemented this study to include an assessment of Belfast’s economic resilience, including relative to other core cities. The study concluded that:

“Belfast requires a series of measures to strengthen its resistance to, and recovery from, economic shocks.”

Belfast had lower resistance and lower recovery capacity than the Core City average measured against twelve other UK cities. Its recovery capacity has been particularly low, being rated as the weakest of all the cities except Liverpool. This is despite the data showing that Belfast’s resistance is strengthened somewhat by the share of public services in the city’s economic output.

This finding underscores that the policy levers required for economic resilience are different to those that focus on economic growth. The high dependency on the public sector as a contributor to the city’s economy has a positive impact on the city’s resistance to shocks; however, it can also have a negative impact on the city’s ability to develop sustainably.

Belfast requires a series of measures to strengthen its resistance and recovery to economic shocks. This is particularly important because the way cities recover from shocks can have permanent impacts on their long term economy. For example, if people who are economically inactive fail to feel the benefits of a return to growth, this can result in a widening of income inequality further reducing resistance to the next shock.

Factors affecting Belfast’s economic resilience

Despite its importance, there is no single global standard or set of indicators for measuring economic resilience. In this section we examine two particular aspects of Belfast’s economic resilience - income inequality and competitiveness and recommend the development of a series of indicators to measure the city’s economic resilience in the future.

Core cities compare Belfast with the GB average

Belfast city’s competitiveness

A recent study of the city’s competitiveness (Baker Tilly Mooney Moore 2019) identified a number of areas of vulnerability for the city of Belfast, and summarised them in the graphic. Importantly, the study found that Belfast’s decline relative to other cities is due to their resurgence, i.e. other cities’ out-performing Belfast.

| Theme | Current average ranking | Three year change | Five year change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Productivity | 4/12 | No change | No change |

| Population and demography | 9/12 | No change | Decline |