Published on 5 October 2023 online

Acknowledgements

Project Management Team

Alan McHaffie - Senior Woodland and Recreation Officer, Belfast City Council

Maria McAleer - Performance and Improvement Officer, Belfast City Council

Kenton Rogers - Project Lead, Treeconomics

Ian McDermott - Technical Lead, Treeconomics

Danielle Hill - Senior Urban Forestry Consultant, Treeconomics

Prepared this Tree Strategy in collaboration with the project managers, the stakeholder group and the individual consultees and experts.

This project was part funded by the Woodland Trust.

Workshop Participants

Dr Mark Johnston MBE - Advisor

Ian McDermott - Advisor

Joe Higginson - Woodland & Recreation Officer, Belfast City Council

Declan Hasson - Planning Officer (trees/landscape), Belfast City Council

Orla Maguire - Biodiversity Officer, Belfast City Council

Anthony Conway - Parks Manager, Belfast City Council

James Noakes - City Innovation Broker, Belfast City Council

Richard McLernon - Project Co-ordinator, Belfast City Council

Malachy Campbell - Senior Policy Officer, NI Environment Link

Malachy Brennan - Regional Grounds Maintenance Manager, Belfast Region, NI Housing Executive

William Hancock-Evans - Senior Lecturer in Global Change Ecology, Queen's University

Trevor McClay - Network Maintenance Manager, Department for Infrastructure Roads

Bill Fulton - Senior Civil Engineer, Department for Infrastructure Roads

Roy Armstrong - Operations Manager, George Best Belfast City Airport

Simon Rees - Regeneration Project Officer, Belfast City Council

Gregor Fulton - Estate and Outreach Manager, Woodland Trust

Nina Schonberg - Nature Recovery Networks Project Manager, Wildlife Trust

Craig Somerville - Partner in Belfast One Million Trees, National Trust

Jim Bradley - Manager, Belfast Hills Partnership

Lisa Critchely - Belfast Hills Partnership

Emma Sharpe - City Regeneration Project Officer, Belfast City Council

Mura Quigley - Adaptation and Resilience Officer Climate Team, Belfast City Council

Mark Whittaker - Senior Planning Officer, Belfast City Council

Project Manager

Senior Reporting Officer - Stephen Leonard, Neighbourhood Services Manager, Belfast City Council

Authors

Kenton Rogers - Treeconomics

Danielle Hill - Treeconomics

Catherine Vaughan-Johncey - Treeconomics

Harry Munt - Treeconomics

Ian Mc Dermott

And for Section 2 - Introduction and Background

Dr Ben Simon - Advisor

Dr Mark Johnston MBE - Advisor

Foreword

Belfast City Council produced this Tree Strategy to help it manage and improve its tree-scape so that it can provide a resilient and diverse urban forest for future generations. The Belfast Tree Strategy lays out a clear vision which focuses on protecting, enhancing and expanding its woodlands, hedges, and trees, connecting people to nature, and ensuring that these continue to be a major asset to everyone who lives in, works in, and visits our city.

We are seeing changes in our weather patterns as a direct result of climate change and trees can help adapt our living environment and mitigate some of the effects of climate change.

The Belfast Tree Strategy reflects the aims of key city partners, including Belfast City Council.

It draws on existing programmes such as Belfast One Million Trees, the Belfast Local Development Plan (LDP), and the Belfast Agenda. It also connects with the Belfast Resilience Strategy, Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan and will deliver 37 key actions over the next 10 years with a review of the strategy once every three years.

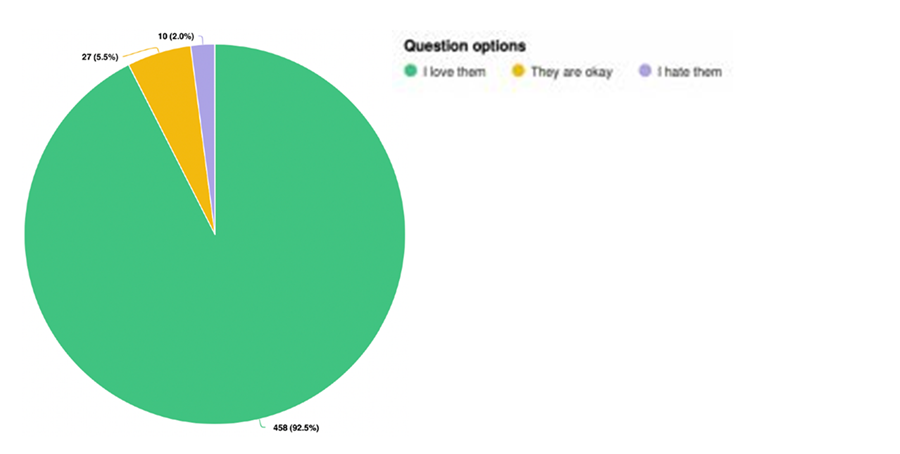

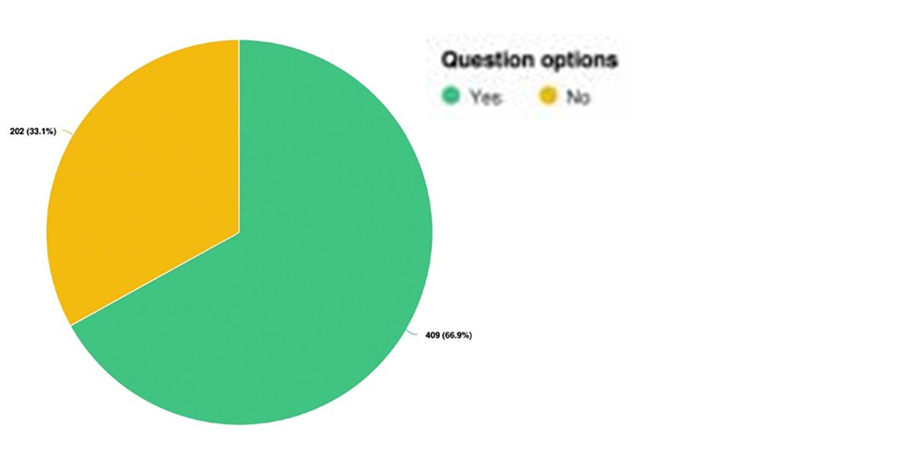

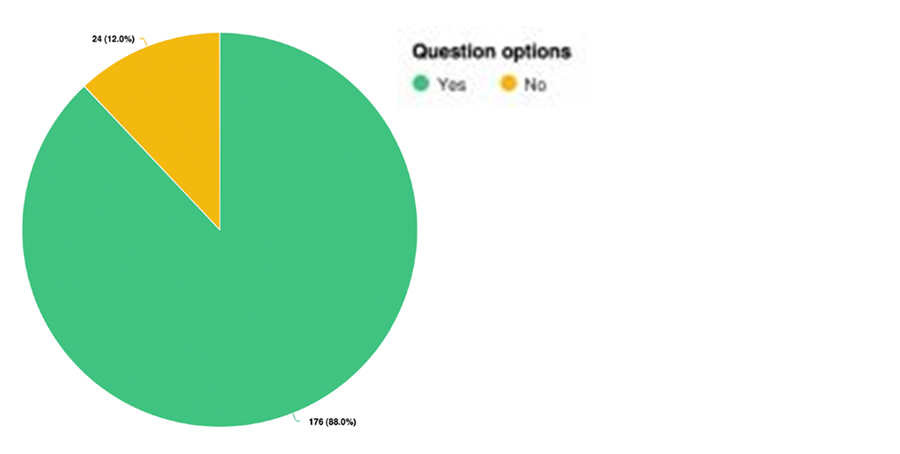

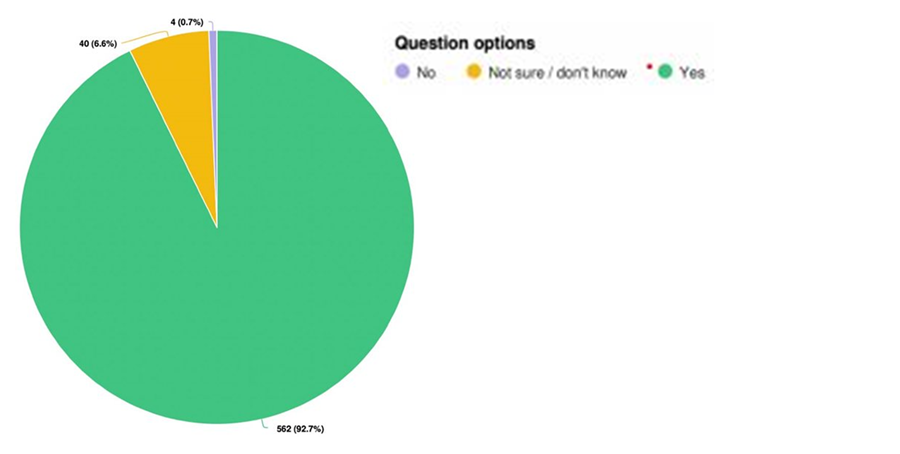

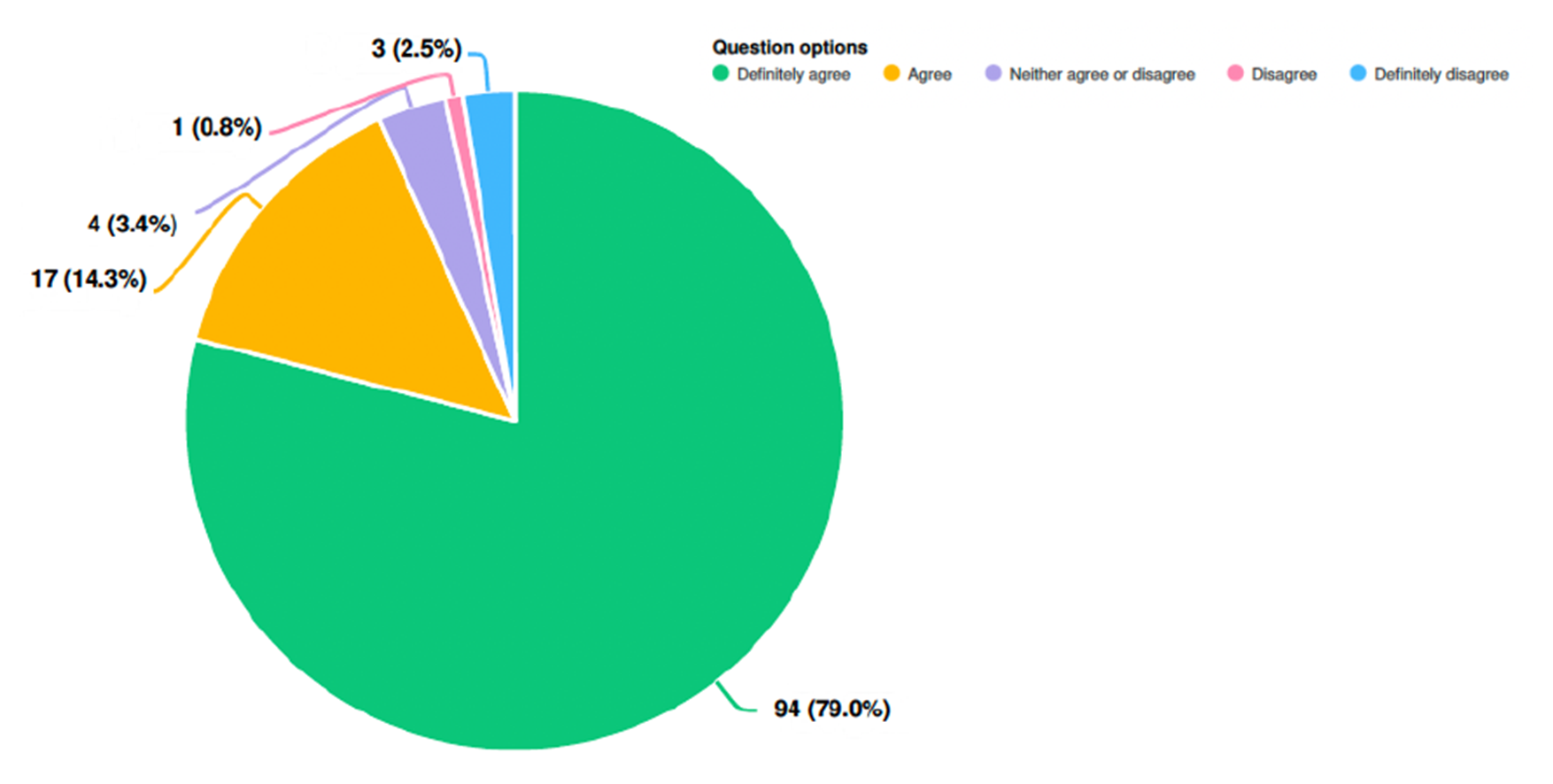

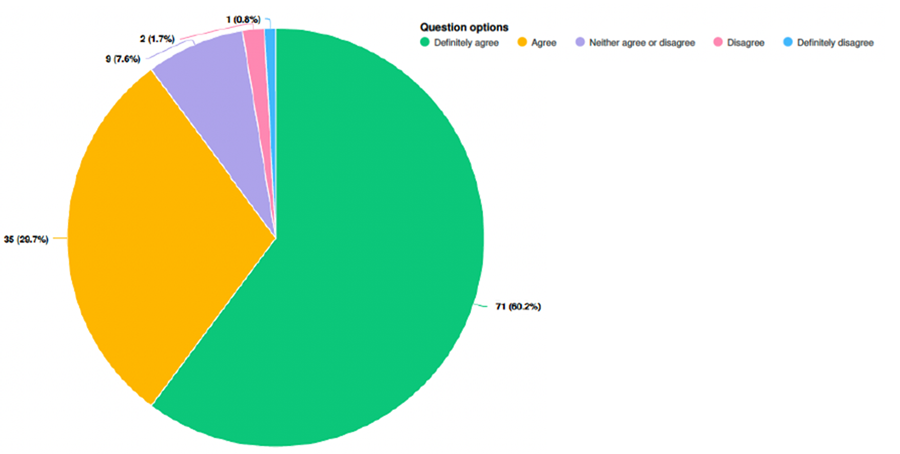

We know through our consultation that there is significant support for the development of this strategy and through this strategy and its delivery we are sending out a clear message, that our city’s trees are valued and need to be protected and cared for over the coming decades.

I am delighted with the commitment and vision council has set out in this strategy and encourage you to read it.

Cllr Micky Murray, Chair of People and Communities Committee

Contents

Acknowledgements

Contents

Section 1

Introduction and Background

1.1 History

1.2 Current State of the Urban Forest

Section 2

Vision

Section 3

Action Plan: Targets, Priorities and Actions

3.1 Trees and Urban Forest Structure

3.2 Community Framework

3.3 Sustainable Resource Management Approach

Approach

Section 4

Consultee Feedback

Section 5

6.1 to 6.6 Technical Appendices

Technical Appendix I: Council Owned Trees

Technical Appendix II: Management Standards for Council Owned Trees

Technical Appendix III: Privately Owned Trees

Technical Appendix IV: Plantations, Shelterbelts & Woodlands

Technical Appendix V: Hazards and Safety

Technical Appendix VI: Policies Adopted by this Strategy

6.7 Bibliography

6.8 Glossary

List of Tables

Table 1: Urban Forest Estimates For Belfast

Table 2: Urban Tree Cover Estimates For Belfast

Table 3: Comparable Cities’ Canopy Cover Estimates And Goals

Table 4: Hazard Zone Categories - Occupancy

Table 5: Hazard Zone Categories - Hazard Level

List of Figures

Figure 1: The 3-30-300 Rule

Figure 2: Belfast Tree Strategy and its relationship to other policies, strategies and initiatives of Belfast City Council

Figure 3: Belfast’s Existing Canopy Cover By Ward

Figure 4: Richards “Ideal” Distribution Of Tree Age Across The Urban Forest Showing Typical Diameter at Breast Height For Each Age Class

Figure 5: Dominance Diversity Curves For UK Cities

Figure 6: Tool To Show Species Suitability And Carbon Sequestration Projections

Figure 7: The Street Lined Trees Of Belfast

Figure 8: Priority Habitats Across Belfast

Figure 9: Heat Map Of PM2.5 Concentration Across Belfast

Figure 10: Example Of Tree Stewardship Map - New York

Figure 11: Map Showing The Hydrology Of Belfast

Figure 12: Map Showing Belfast’s Queen’s University Campus And Surrounding Green Space

Figure 13: Tree Canopy Cover Across Belfast From Sentinel Data

Figure 14: Indices Of Multiple Deprivation Ranking By Ward

Figure 15: Trees And Design Action Group Species Selection Criteria Guide

Figure 16: Belfast’s Interactive Online TPO Map

Figure 17: Map Of Nature Reserves, SSSIs and Other Public Areas

Figure 18: Tree Pest And Disease Introduction In The UK

Figure 19: Uses Of Urban Wood

Figure 20: Ancient Trees Around Belfast

Figure 21: Torbay’s Open Access Webmap

Section 1 - Introduction and Background

“It is that range of biodiversity that we must care for - the whole thing - rather than just one or two stars.”

David Attenborough

“Some of my local streets have trees, some do not. I think all the streets should have them. During hot spells they provided much needed shade and improve the environment markedly.”

Belfast Resident and consultation respondent

1.1 History

The earliest descriptions of the landscape around the northern Lagan Valley date from the late 16th century. A map from this period by Francis Jobson is of particular interest as it distinguished areas with tall growing trees from areas of scrub. Jobson indicated that the lands southeast of Lough Neagh and in mid-Down had tall woodland trees. The districts around Carrickfergus, North Down and the Ards Peninsular were largely devoid of woodland and the Lagan Valley contained predominantly underwood.

With the development of the town of Belfast in the 17th century, much of the woodland in the northern Lagan Valley was cleared for agriculture, cut for firewood or used in industries such as ship building, tanning and charcoal-making for ironworks. However, some leases instructed tenants to retain trees and plant hedges and saplings, and surviving records for the Donegall estate from the 1730s and 1740s refer to the employment of men termed ‘wood rangers’, who looked after trees and hedges. A large woodland was retained at Cromac (lower Ormeau) until the 1790s, when the last trees described as principally oak with some ash and alder were felled. Also, recent tree ring dating at Belvoir Park has demonstrated that some of the imposing oaks that today grace this site have grown undisturbed since the mid - 17th century.

In the second half of the 18th century large scale tree planting started, supplied by local nurseries that advertised the sale of a wide variety of species including non-native trees and fruit bushes. Planting continued during the Victorian era in gardens, estate lands, on hill slopes such as Cave Hill, Colin Glen and Cregagh Glen.

Following the formation of the Belfast Botanic and Horticultural Society in 1827 a 14-acre site was purchased at the junction of the Malone and Stranmillis Roads for the Belfast Botanical Garden which opened in 1828. Its diverse collection of trees and shrubs from around the world were primarily for the enjoyment of the Botanic Society’s members until it became a public park in 1895 when the Belfast Corporation bought the gardens. Belfast's first public park (Ormeau Park) in the south of the city, opened in 1871 on land adjacent to the River Lagan, that was formerly part of the Donegall family estate. It already had many fine mature trees and these were supplemented by much new planting. In the late 19th and early 20th century, several new and extensive public parks were opened by Belfast Corporation, many of which also had plenty of fine mature trees. Following the Belfast Burial Ground Act (1866) the Corporation opened the Belfast City Cemetery near the Falls Road in 1869. This was followed by a number of other public and private cemeteries that added greatly to the city’s open space and tree cover.

In 1900, the Corporation formed its Cemeteries and Public Parks Committee from what had previously been two separate committees. This was the forerunner of Belfast City Council’s City and Neighbourhood Services Department that now manages some 49 public parks, 9 cemeteries, and the vast numbers of trees and shrubs within them.

In 1900, the Corporation formed its Cemeteries and Public Parks Committee from what had previously been two separate committees. This was the forerunner of Belfast City Council’s City and Neighbourhood Services Department that now manages some 49 public parks, 9 cemeteries, and the vast numbers of trees and shrubs within them.

In 1846, Belfast Corporation established the Improvements Committee, part of whose duty was to initiate street tree planting. Unfortunately, there is little recorded evidence of this earliest planting. In 1900, street tree planting was taken over by the newly-formed Cemetery and Public Parks Committee. Most of these early street tree plantings were undertaken before and immediately after the First World War and comprised a limited range of species such as limes and London planes. By the late 1960s, pollution in the city had reduced to a level where a greater variety of species could be planted, such as hornbeam, cherry, birch, and rowan. From the late 1980s, systematic street tree planting in Belfast increased significantly with many more roads being planted, particularly in the suburbs. A considerable amount of this planting was initiated by the Belfast Development Office and by 1993 there were over 9000 street trees recorded on Belfast City Council’s tree inventory.

Throughout the 20th century, Belfast’s suburbs expanded steadily and many of the new residential properties, particularly in the wealthier districts, had quite large gardens. With the increasing popularity of gardening as a pastime, many were planted with some trees and shrubs, which then contributed substantially to the overall tree cover in the city. In contrast, much of the 20th century was marked by decades of neglect of woodlands and the felling of trees when the grounds of former big houses and private estates were sold.

In the period following the Second World War both statutory and voluntary organisations started to promote trees and woodlands and to advocate the protection of trees. The first big tree campaign in Northern Ireland was launched by the National Trust in 1945 to save woodland at Colin Glen in west Belfast. Tree Week was initiated in Northern Ireland in 1967 and has since been adopted throughout the UK as the main annual celebration of trees. The protection of trees through Tree Preservation Orders was introduced into Northern Ireland legislation in 1973.

By the 1970s it was widely acknowledged that because of a lack of planting and management, most woodlands had an uneven age structure, with a predominance of mature trees and few saplings or developing trees. In response, statutory organisations together with voluntary sector environmental organisations started to develop large scale tree planting projects and place greater emphasis on tree care.

The need for a co-ordinated approach in the planting, maintenance and management of city trees led to the development of the Forest of Belfast (FoB) urban forestry initiative, which was launched in 1992. Its original thrust was as an urban planning initiative and this led to the concept of urban forestry being given official recognition in Northern Ireland. The establishment of an extensive urban forest was included as an objective in the draft of the Belfast Urban Area Plan (published by the Department of the Environment (NI) in November 1987 and confirmed in the final document published in 1990 (DoE(NI), 1990).

The Forest of Belfast then developed into a city-wide urban forestry initiative involving a partnership of the public, voluntary and private sectors and operated for over two decades. During this time the project produced a comprehensive survey of Belfast’s trees, detailing the structure and composition of the tree cover, as well as its condition and ownership. Not only was this data crucial for informing where Belfast should be tree planting in the 1990s and early 2000s, it also serves as a useful datum point and yardstick for measuring its impact today against the more recent i-Tree Eco urban forest survey.

In recent years new tree schemes have been developed, such as the Million Trees Belfast initiative, and public support for trees and tree planting continues to grow. There is now widespread awareness of the importance of trees for recreation, amenity and for our mental health and well-being; for increasing biodiversity and for mitigating climate change. In addition, the need for planting and management to counter an increasing number of tree pests and diseases is widely appreciated.

What is the urban forest?

The urban forest consists of all the green infrastructure in an urban area. This includes trees, hedges, and vegetation which can be found anywhere from deliberately planted roadside trees to vegetation found in bodies of water. The urban forest provides benefits to those who live among it. These benefits include, air pollution removal, carbon sequestration and storage and reducing flood risk. Other social benefits such as an increase in house value, amenity value of trees and health benefits for residents are also increased in a diverse, healthy urban forest.Further Reading

- Britt, C and Johnston, M (2008) Trees in Towns II: A new survey of urban trees in England and their condition and management. Department for Communities (DfC) and Local Government:

London - DoE Roads Service (1993) Belfast Street Trees. Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland: Belfast.

- Johnston, M (1995) The Forest of Belfast: healing the environment and the community. Arboricultural Journal 19, 53-72.

- Scott, R. (200) A Breath of Fresh Air: The Story of Belfast’s Parks. The Blackstaff Press: Belfast.

- Segoviano, A (1995) Belfast's Trees - A Survey of Trees in Greater Belfast. The Forest of Belfast Project: Belfast.

- Simon, B (2009) If Trees Could Talk: The story of woodlands around Belfast. The Forest of Belfast: Belfast.

1.2 Current State of the Urban Forest

The urban forest of Belfast is a vital resource for the city and the rapid growth of statutory and voluntary organisations undertaking tree projects prompted the inclusion of a policy on urban forestry in the Belfast Urban Area Plan 2001 (Published in 1990). This policy to ‘make trees an integral part of the urban fabric led to the formation of the Forest of Belfast urban forestry partnership to support a more strategic approach to tree planting and tree care. One of its very early tasks was a comprehensive survey of trees throughout Greater Belfast.

Some of the key findings of this study, Belfast's Trees (Segovinao, 1995) are reproduced in Table 1 alongside data from the 2022 i-Tree Eco urban forest assessment. It is encouraging to see that at first glance there has been significant improvement on tree numbers, tree cover and density, a testament to previous tree planting initiatives such as the community woodlands initiatives of the 60’s and 70’s, the Yew trees for the new millennium campaign and the work of the Conservation volunteers millennium tree campaign, which had planted half a million trees by 1991.

However, 14.5 per cent tree cover is still short of the 20 per cent recommended by Forest Research and the 30 per cent target by the 3-30-300 rule recommended by the IUCN. The task ahead is huge, but not impossible. Belfast’s current One Million trees campaign will go a long way to help achieve this target but only if it is complimented with other programs, that not only plant the right trees, in the right places for the right reasons, but are also able to provide care and maintenance, involve communities and measure the outcomes (both good and bad), take stock, learn and continually improve.

This strategy reflects the aims of key city partners, including Belfast City Council, existing programmes such as Belfast One Million Trees, the Belfast Local Development Plan, the Belfast Agenda and also clearly links tree planting and management with Belfast’s climate ambitions and the benefits that trees provide to health and wellbeing. The Tree Strategy will have a 10-year lifespan from its launch date and sets out a commitment to delivering key Priorities and Actions for the next 3 years.

The 37 targets, priorities and actions laid out in this 10-year Tree Strategy document will build on Belfast's previous successes and include actions around sustainable management, community engagement and on ongoing measurement of the structure and composition of Belfast's urban forest.

With ever growing concern about climate change, the loss of biodiversity and the need for sustainability we need to take action now to ensure that future generations can continue to benefit from Belfast's trees long into the future and that Belfast is able to achieve its ambitious vision for the urban forest.

What is the 3-30-300 rule?

This rule of thumb provides clear criteria for the minimum provision of urban trees in our urban communities at the same time, it is straightforward to implement and monitor – and easy to remember.

- You should be able to see 3 trees from your window

- There should be 30 per cent tree cover in every neighbourhood

- You should only be 300m or less from your nearest park

Sources and References

- Hill, D., Ruddick, J. and Walker, H. (2022). Valuing Belfast’s Urban Forest - Technical Report. Treeconomics Ltd. Last accessed: 13/07/2022. Available online: https:// www.treeconomics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Belfast-i-Tree-Eco-report.pdf

- Konijnendijk, C. (2021) The 3-30-300 Rule for Urban Forestry and Greener Cities

- Segoviano, A. (1995). Belfast’s Trees - A survey of Trees in Greater Belfast.

- The Forest of Belfast Project The Forest of Belfast. (1994) A Strategy Document. The Forest of Belfast Project

Section 2 - Vision

“That Belfast is a city which focuses on protecting, enhancing and expanding its woodlands, hedges, and trees, connecting people to nature, and ensuring that these continue to be a major asset to everyone who lives in, works in, and visits our city.”

Vision

Although the Vision has a city-wide scope, it is important to work at the neighbourhood level, together with local communities and stakeholders, to ensure the successful implementation of the plan.

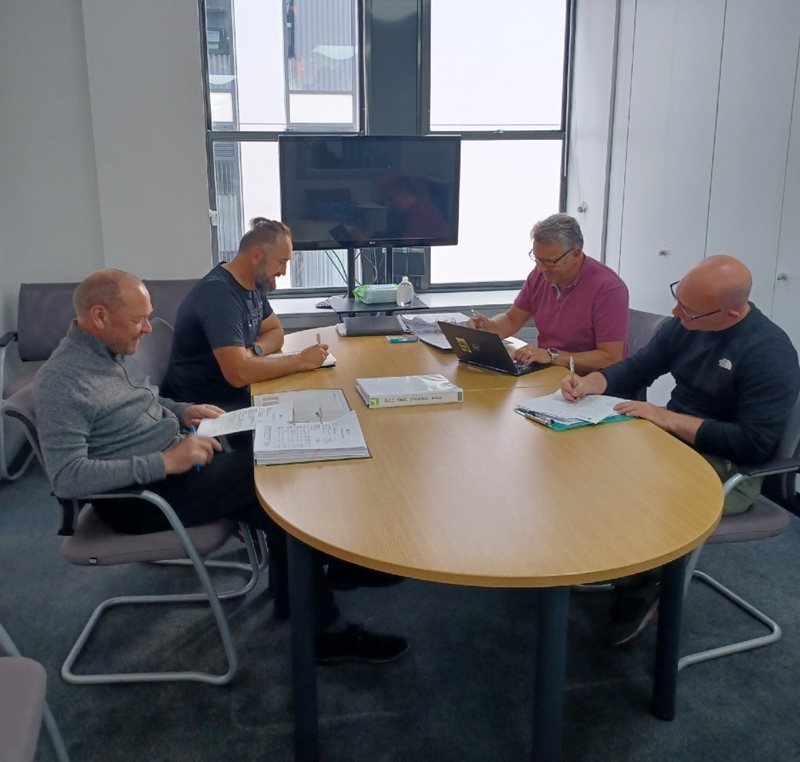

This new Tree Strategy is championed by Belfast City Council and Belfast One Million Trees, and was developed in a collaborative process over series of workshops with representatives of the local government; interest groups; and representatives of the community; and with the support of Treeconomics. The Strategy outlines key topics, priorities, and actions under three central themes:

- Trees and Forest Structure

- Community Framework

- Sustainable Resource Management Approach

The Strategy is structured around a comprehensive set of key performance indicators, informed by the current state of evidence and best practice. For each of these performance indicators, an assessment of the current situation is made, ambitions are laid out, and priorities are identified. Moreover, specific actions and roles and responsibilities are defined.

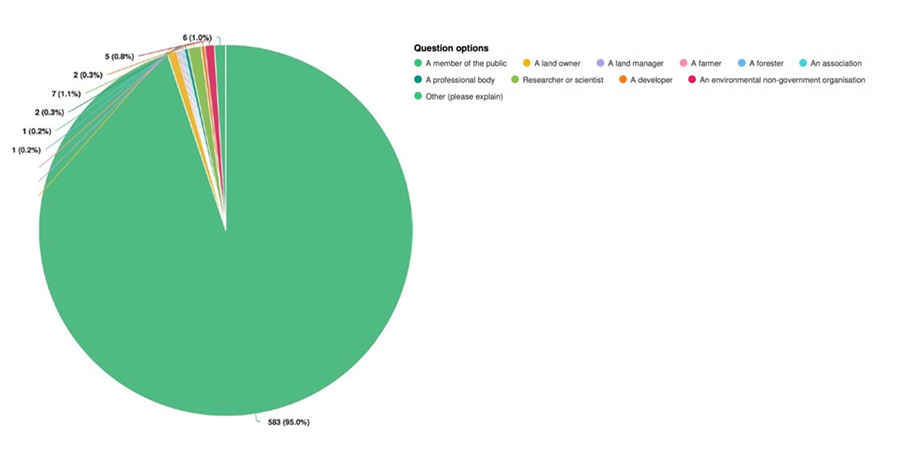

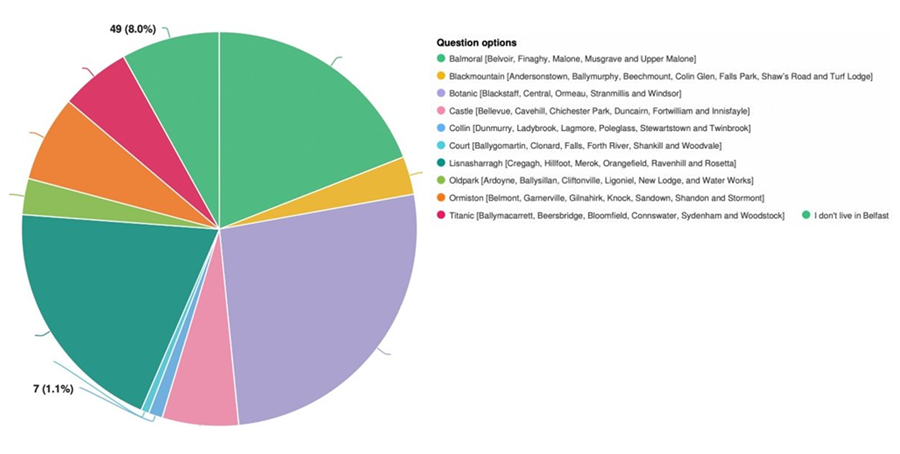

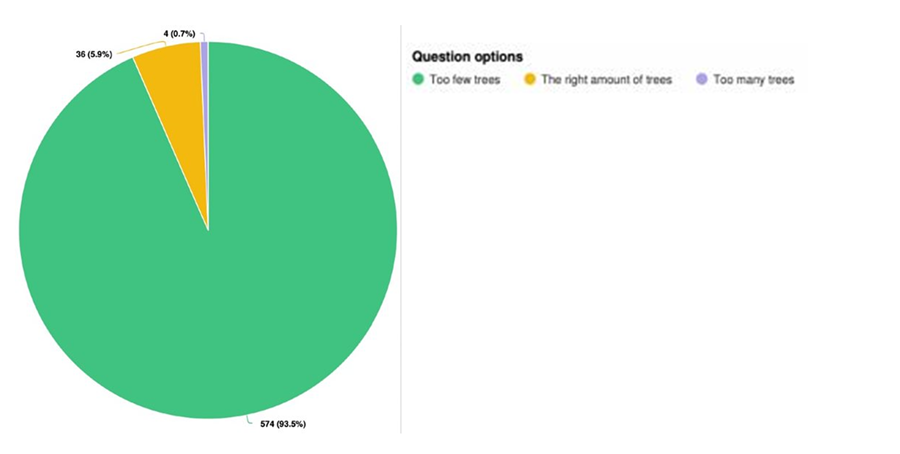

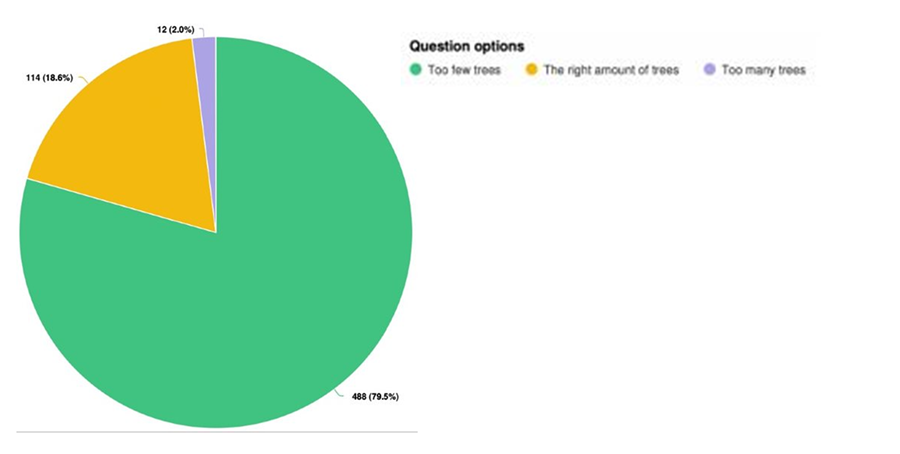

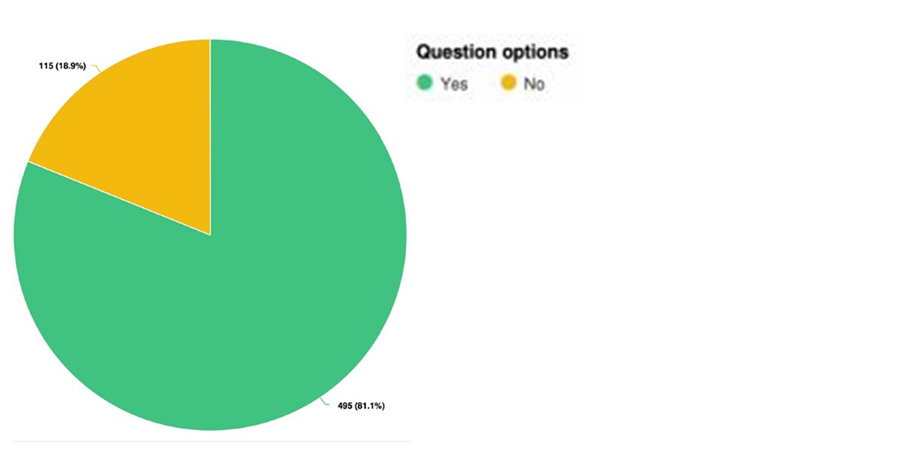

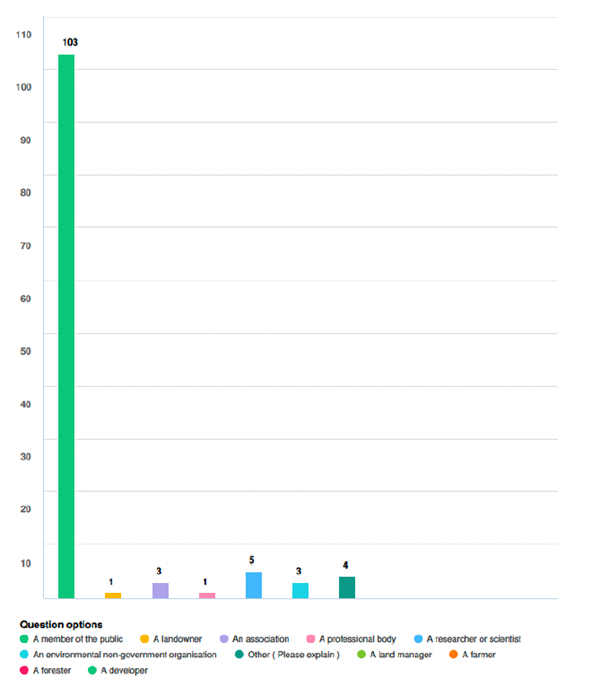

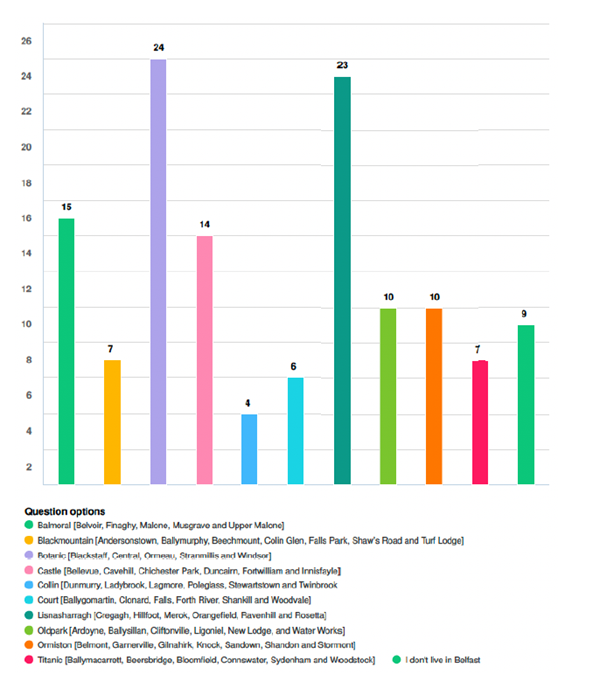

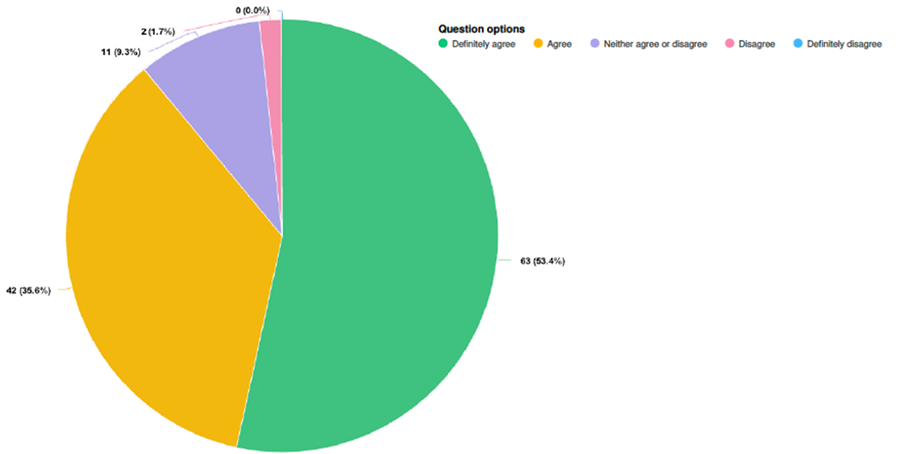

In addition, an initial public consultation was also undertaken as part of this strategy. The online survey questionnaire was one of the most popular posted by Belfast City Council with 615 respondents and 200 pages of feedback. Further details and highlights are provided in Appendix V.

This ambitious Tree Strategy is an important step forward. Its future implementation, with a co-ordination role for Belfast City Council and in collaboration with a wide range of local partners and members of the community, will make the city greener, healthier, and more resilient to climate and other challenges.

The table in Figure 2 lists some policies, strategies and initiatives of Belfast City Council and Central Government departments.

Figure 2: Belfast Tree Strategy and its relationship to other policies, strategies and initiatives of Belfast City Council and Central Government departments

|

Programme for Government |

Climate Change Act NI 2022 |

|---|---|

|

Regional Development Strategy |

|

|

Green Growth Strategy |

|

|

DAERA Forests for our Future Initiative |

|

|

Second Cycle Northern Ireland Flood Risk Management Plan 2021-2027 |

|

|

NI Climate Adaption Programme |

|

|

Strategic Planning Policy Statement |

|

|

Belfast Local Development Plan |

Belfast Agenda |

|

|

Belfast Resilience Strategy |

| One Million Trees Programme | |

|

|

Belfast Tree Strategy |

|

|

Net-Zero Carbon Roadmap |

Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan |

|

|

Belfast Open Spaces Strategy (BOSS) |

Potential Future Strategies |

|

Playground Improvement Plan |

Local Biodiversity Action Plan |

|

Tree Strategy Action Plan |

Habitats Strategy |

|

Cemeteries and Crematorium Improvement Programme |

Climate Action Plan |

| Gardens and Community Gardens and Allotments | |

| Watercourse and Bodies | |

| Landscape Character | |

| Playing Pitches Strategy | |

| Area and Neighbourhood Plans Interventions | |

| Site Based Management Plans Green Flag Management Plans |

|

Section 3 - Targets, Priorities and Actions

“It seems to me that we all look at Nature too much, and live with her too little”

Oscar Wilde

1.Trees and Urban Forest Structure

“Apart from the obvious environmental benefits of trees /shrubs ie cleaning the air by removing toxins, wildlife habitat, biodiversity. They also provide essential shade for walkers, cyclists, animals etc who frequent the area.”

Belfast Resident and consultation respondent

3.1 Targets, priorities and actions

T1 Relative Tree Canopy Cover

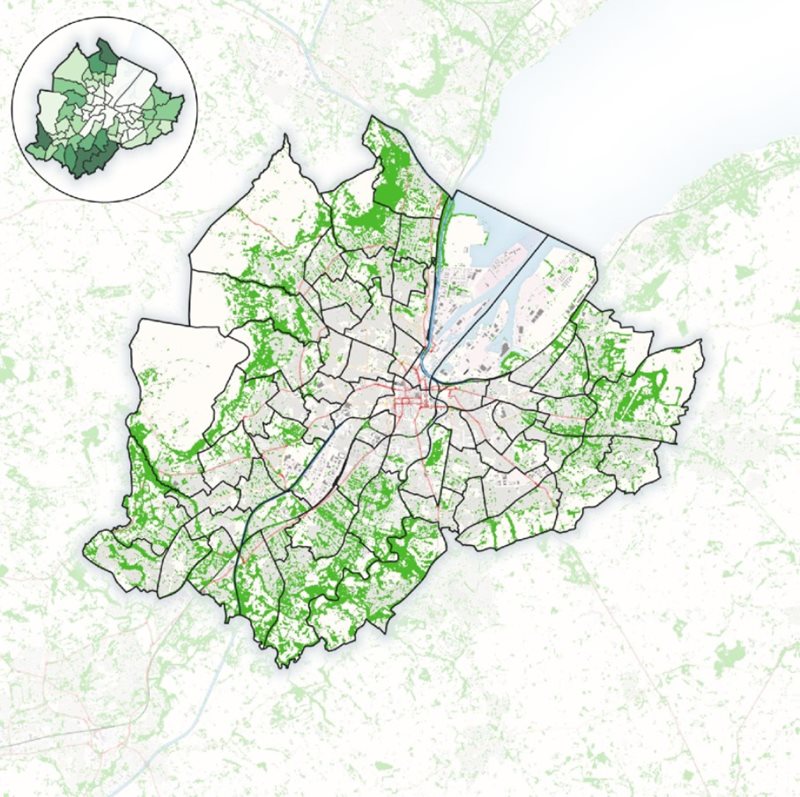

Tree Canopy Cover, which is often also referred to as tree cover or urban canopy cover, can be defined as the area of leaves, branches, and stems of trees covering the ground, across a given area, when viewed from above. Canopy cover is a two dimensional metric, indicating the spread of canopy cover across an area. Assessing canopy cover is popular because it is relatively simple to determine from a variety of means and it can be calculated at relatively little expense.

There are many methods of assessing canopy cover at this scale, including i-Tree canopy, i-Tree Eco, Sentinel satellite data, Bluesky National Tree Map, etc. These methods are not directly comparable with each other as they use different metrics and definitions of what constitutes canopy cover. Going forward Belfast will identify a suitable method of assessment so that repeat surveys are consistent and can be compared in order to track and monitor performance.

It has also been acknowledged that for any future assessment it will be important to be able to differentiate between the tree canopy cover also provided by Woodlands, Hedges, Parks, Open grown and Street trees.

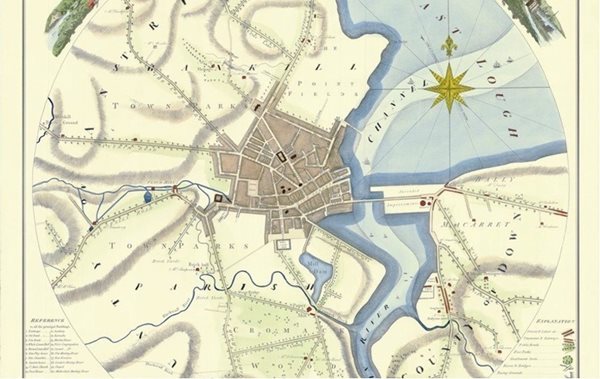

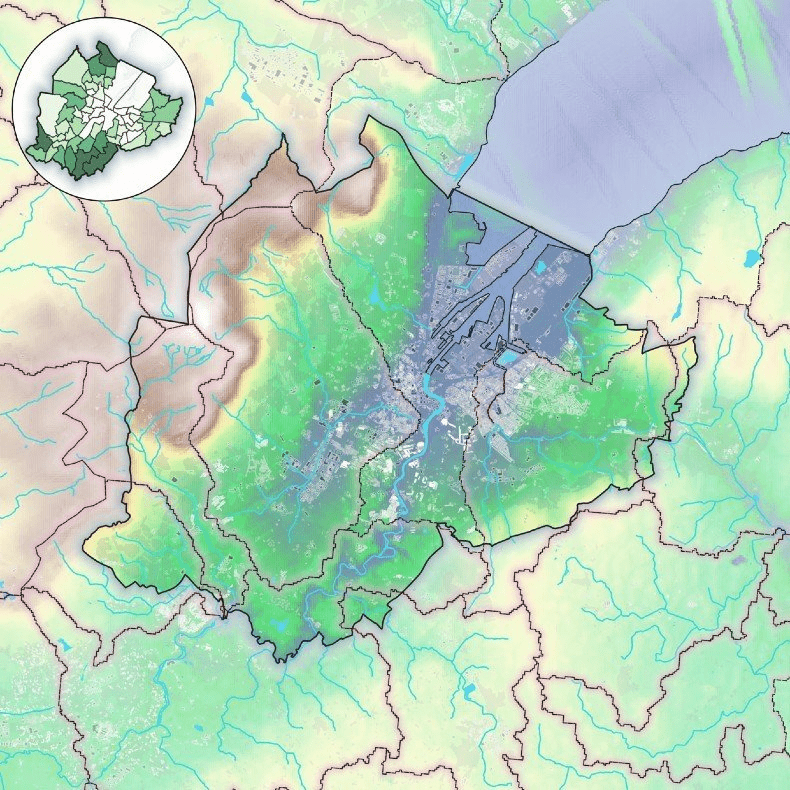

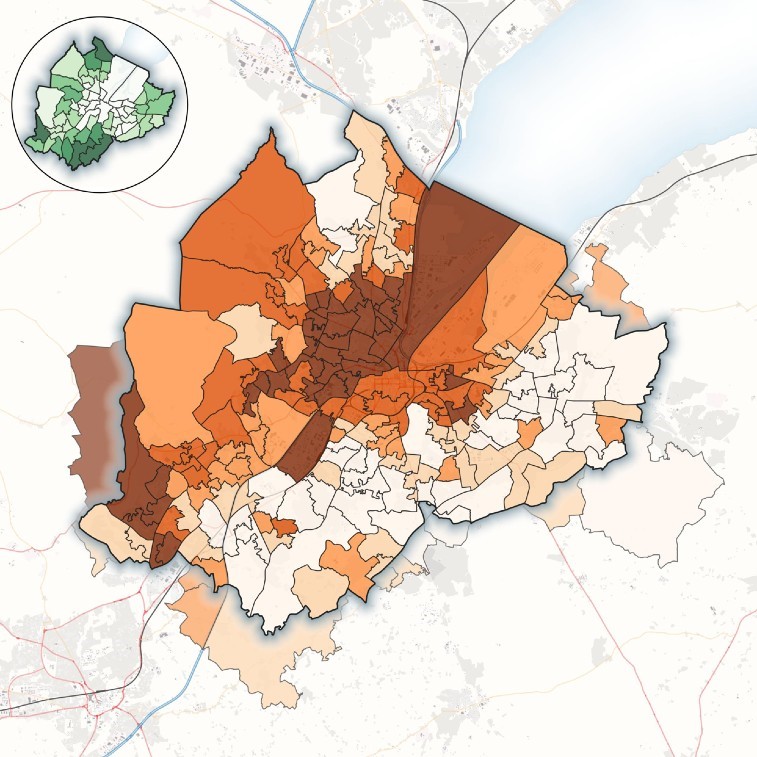

Figure 3: Belfast's Existing Canopy Cover Percentage by Ward measured with Sentinel Satellite Data

© OpenStreetMap contributors Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2022.

© contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2017), processed by CBK PAN

Actions

- Carry out a detailed canopy cover assessment to establish accurate potential canopy cover and the amount of tree cover also provided by woodland and hedges.

- Review every 5 years by carrying out a canopy cover assessment.

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for Action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| High | 1-2. Belfast City Council | To be confirmed - short term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| The existing canopy cover equals 0–25 per cent of the potential. | The existing canopy cover equals 25–50 per cent of the potential. | The existing canopy cover equals 50–75 per cent of the potential. | The existing canopy cover equals 75–100 per cent of the potential. | |

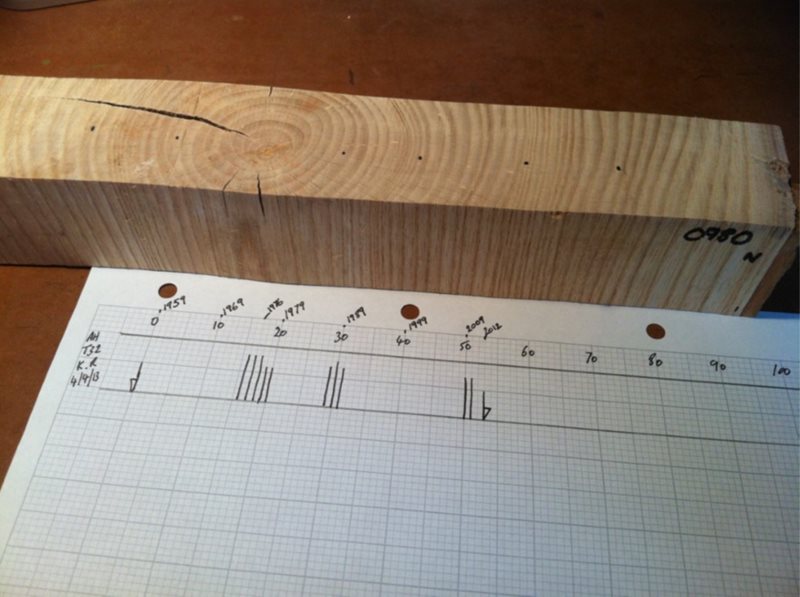

T2 Size (Age) Diversity

A healthy urban forest relies on its age diversity to maintain its ability to provide constant benefits to the people who live in Belfast over time. Maturing trees must be protected and managed to ensure they thrive and survive to become veteran trees (senescent), and juvenile trees must be planted constantly to replace old trees, dying trees, and trees removed for safety reasons. Larger, older trees typically provide more annual benefits than smaller, younger trees. However, these younger trees are vital to maintaining a healthy and sustainable forest.

Generally, the most accurate way to gauge age diversity is to compare current tree size in each species (in terms of diameter at breast height, or DBH) to the maximum diameter for that species. The goal would then be to maintain a tree population that is unevenly distributed among different age classes, making sure that there are enough juvenile trees for the future.

It is of course also important to strive for age diversity across the entire tree population – including public trees managed “extensively” (as a group) in parks and natural areas, as well as trees on private property, both city-wide and at neighbourhood level.

The recent i-Tree Eco study for Belfast gives the current age diversity across all trees as: 67 per cent Juvenile, 24 per cent Semi - Mature, 8 per cent Mature and 1 per cent Senescent.

Figure 4: Richards “Ideal” Distribution of Tree Age Across the Urban Forest Showing Typical DBH for Each Age Class.

Sources and references:

Richards, N.A., (1982/1983). Diversity and stability in a street tree population. Urban Ecology 7, 159–171 – as cited in McPherson, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 12 (2013) 134– 143.

Actions

- Review every 10 years

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1. Belfast City Council, Belfast Hills, One Million Trees | TBC - Medium term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Even age distribution or highly skewed toward a single age class. | Some uneven distribution, but most of the tree population falls into a single age class. | Total tree population across municipality approaches an ‘ideal’ age distribution of 40 per cent juvenile, 30 per cent semi-mature, 20 per cent mature, and 10 per cent senescent. | Total population approaches that ideal distribution borough-wide as well as at the ward level. | |

T3 Species Diversity

Diversity is an important aspect of the urban forest to monitor. Trees are split into families, genera, species and varieties and it is essential to have a mix of these to create a diverse urban forest. However, maintaining a high level of both inter- and intra- species diversity is also key to urban forest sustainability. Sufficient tree diversity can increase overall resilience in the face of biotic and environmental stresses and threats. A more diverse tree-scape is better able to deal with possible changes in climate or pest and disease impacts.

Understanding the species diversity of Belfast’s existing urban forest is a vital first step. From there, tree planting and management plans can enhance the diversity in line with the goals and KPI’s of the action plan. The recent i-Tree Eco study indicates that Belfast's top three most common species (Ash - 11 per cent, Sycamore - 9 per cent and Beech - 5 per cent) account for 25.8 per cent of the population.

Santmour’s (1990) 10-20-30 rule for species, genus and family, and Barker’s benchmark of 5 per cent per species are useful tools in assessing and providing targets for species diversity in the urban forest. Ideally, the array and location of suitable tree species would be so diverse that no single species would represent more than 5 per cent of the tree population across the municipality or more than 10 per cent in any given neighbourhood. However these rules apply only to street tree populations.

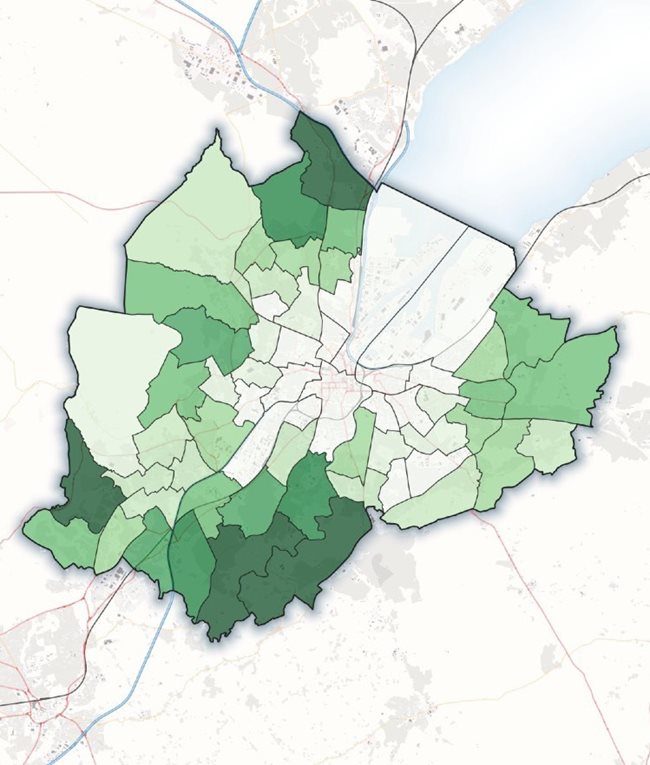

For landscape scale approaches Hubbell’s dominance diversity curves can be a more useful aid to visualise species diversity. The longer and shallower the curve, the greater the diversity.

Figure 5: Dominance diversity curves for UK cities compared with example forest types

Sources and references:

Santamour, F.S. (1990) Trees for urban planting: Diversity, uniformity and common sense, in: Proceedings of the Conference Metropolitan Tree Improvement Alliance (METRIA). pp. 57–65.

Barker, P.A. (1975) Ordinance Control of Street Trees. Journal of Arboriculture. 1. pp. 121-215.

Beeauchamp, K. 2016 Measuring Forest Tree Species Diversity. Forest Research.

Rosindell, J., Hubbell, S.P. and Etienne, R.S., 2011. The unified neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography at age ten. Trends in ecology & evolution, 26(7), pp.340-348.

Actions

- Assess Belfast’s street tree diversity to Santamour’s Rule and also across the entire urban forest using Hubbell’s dominance diversity curve method.

- Review every 10 years.

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| High | 1. Belfast City Council 2. Research Partner |

To be confirmed - short term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Five or fewer species dominate the entire tree population across municipality. | No single species represents more than 10 per cent of total tree population; no genus more than 20 per cent; and no family more than 30 per cent. | No single species represents more than 5 per cent of total tree population; no genus more than 10 per cent; and no family more than 15 per cent. | At least as diverse as “Good” rating (5/10/15) municipality-wide – and at least as diverse as “Moderate” (10/20/30) at the neighbourhood level. |

|

T4 Species Suitability

Species suitability involves selecting a broad array of species which are well suited to both the urban and regional environment.

Trees have unique needs; all tree species have different genetic characteristics and growth strategies which have been developed to maximise survival and growth in their natural habitats. Climate, soil, and other environmental aspects can affect their ability to survive and thrive. In cities, trees are subject to more external stresses than their woodland counterparts, and this can limit their lifespan and make them more susceptible to pests and disease. By promoting the planting of suitable species in suitable locations, trees are less likely to suffer from these stresses and therefore reach their full potential.

The determination of species suitability should take into account concerns such as adaptability to local climate and future climate change, invasive potential, soils, moisture demands, disease risk, and management considerations.

Checking plant hardiness zones is a good place to start. The USDA-designed system maps zones on minimum temperatures, and is now available for the rest of the world. Forest Research have developed a climate matching tool (https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/fthr/climate-matching-tool/) which may be of some use in predicting future climates. FR’s Ecological Site Classification Decision Support System (ESC-DSS) found online at https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/fthr/ecological-site-classification/ can indicate a trees suitability depending on a range of factors such as soil moisture and nutrient regime, climate and topography etc.

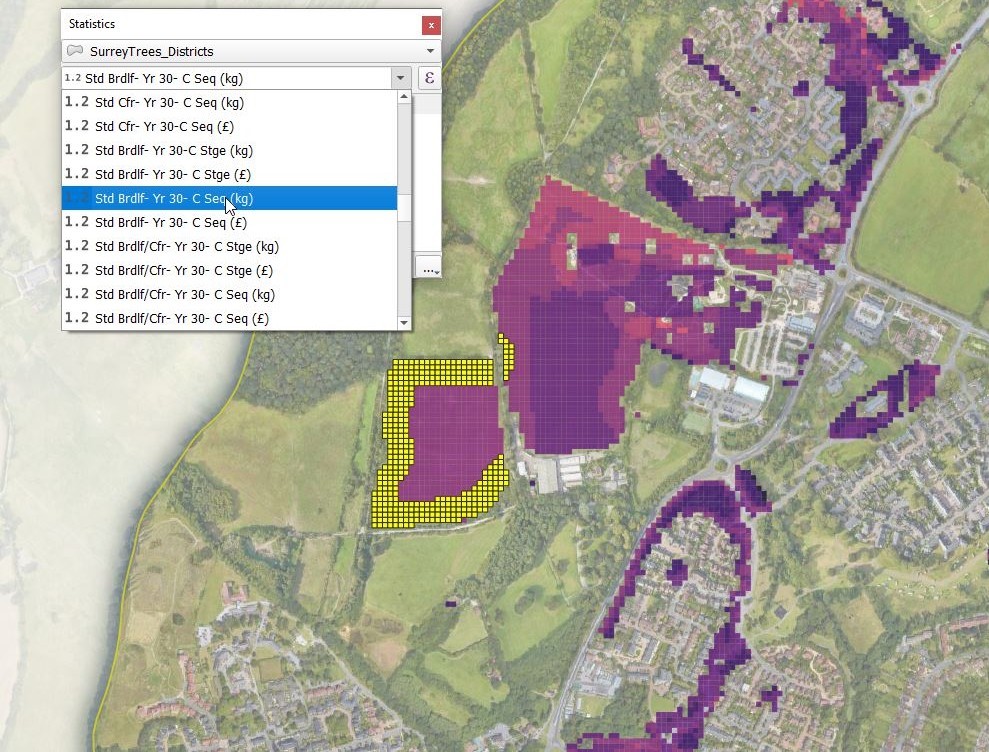

In the example opposite, species suitability has been mapped using multiple different layers in an interactive tree planting opportunity map which also displays potential carbon storage and sequestration.

Figure 6: Tool to show species suitability and carbon sequestration projections

Actions

- Assess species suitability across Belfast for a changing climate.

- Establish Native - Non-Native Guidelines for urban and rural areas.

- Explore how to include Intra Diversity.

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1-3. Belfast City Council | TBC - Medium to Long term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Fewer than 50 per cent of all trees are from species considered suitable for the area and for projected climate. | >50 per cent-75 per cent of trees are from species suitable for the area and for projected climate. | More than 75 per cent of trees are suitable for the area and for projected climate. | Virtually all trees are suitable for the area and for projected climate. | |

T5 Publicly Owned Trees

Trees managed individually, such as street trees, are considered to be “managed intensively,” according to arboricultural techniques – whereas trees in woodlands or other natural areas are typically “managed extensively,” as a group. Park trees or trees on institutional campuses can fall into either category, depending on how they are managed.

Understanding how many trees are managed in this way and what this type of management entails will help provide a baseline for improving future ‘intensive’ practices. A tree inventory documenting these trees, their location, species, health, etc is invaluable for tree maintenance and risk management.

Belfast already uses a tree inventory system for the street trees and those in parks. This includes detailed condition ratings and historic and planned maintenance. The next step is to migrate this system to a GIS based platform.

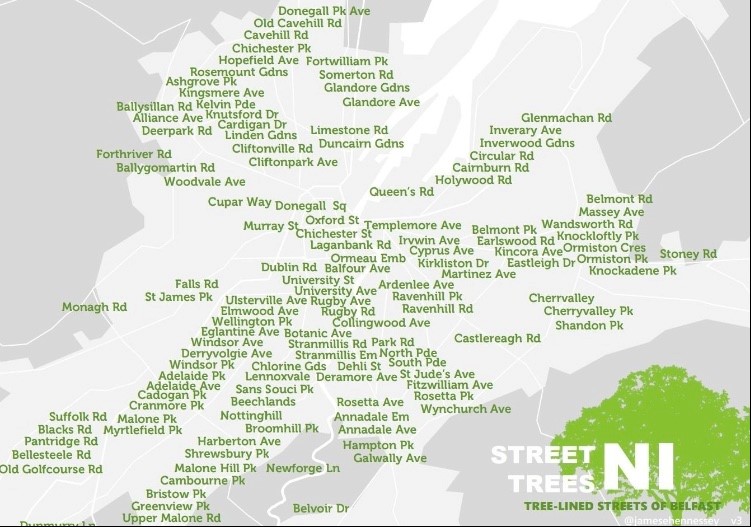

Figure 7: The street lined trees of Belfast

Actions

- Move to an integrated GIS based tree inventory system.

Relevant corporate policies

- Belfast Open Spaces Strategy

- Belfast Metropolitan Transport Plan

- Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Belfast City Council | TBC - Medium term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Condition of urban forest is unknown. | Sample-based tree inventory indicating tree condition and risk level. | Complete tree inventory that includes detailed tree condition ratings. | Complete tree inventory that is GIS-based and includes detailed tree condition as well as risk ratings. | |

T6 Publicly Owned Woodlands and Natural Areas

Trees in woodlands or other natural areas are typically “managed extensively,” as a group whereas trees managed individually, such as street trees, are considered to be “managed intensively,” according to arboricultural techniques (See T5). Park trees or trees on institutional campuses can fall into either category, depending on how they are managed.

Understanding how many trees are managed in this way and what this type of management entails will help provide information for improving future ‘extensive’ practices.

Natural area surveys that incorporate patterns and structures of ecological functions would be useful. Woodland fragmentation, recreational overuse, disturbance and invasives such as Rhodedendron have all been highlighted as issues of serious concern, which are as yet unquantified.

Developing individual management plans and a web map for these areas could be a useful tool for both management, community engagement and connectivity. Current ‘extensive’ management methods should be reviewed and updated if necessary.

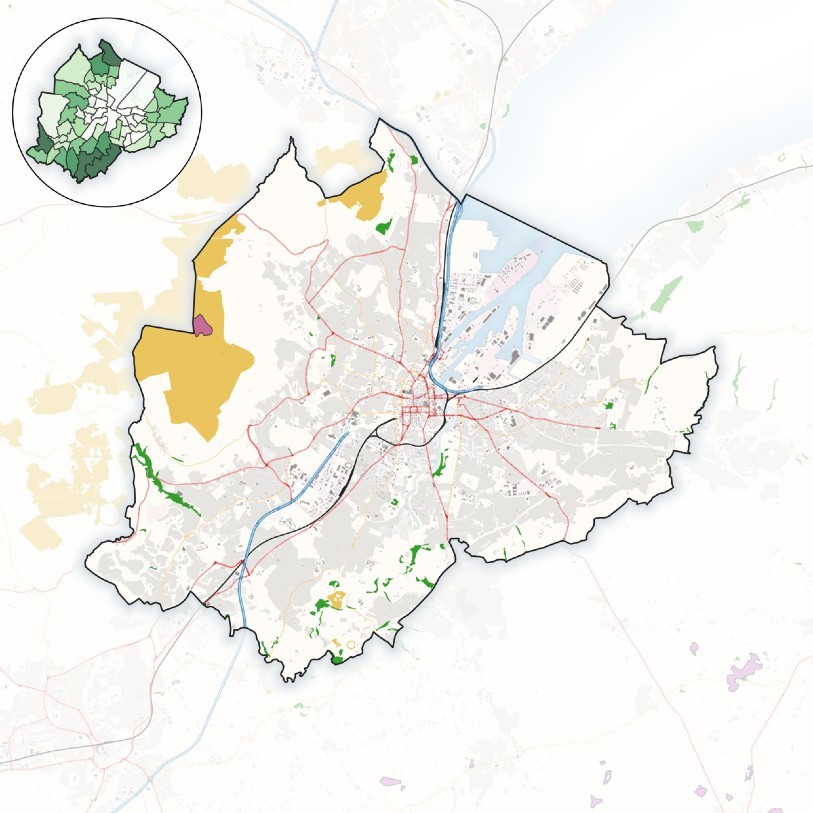

Figure 8: Priority habitats with high ecological importance across Belfast (Inset: Canopy cover by Ward)

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2022. © OpenStreetMap contributors

Actions

- Carry out benchmark surveys on the nature and extent of Natural areas including Woodland and Hedgerows and assess usage level and patterns, threats, ecology and function of these natural areas.

- Develop Targets, Priorities, Actions and KPI’s for these areas for inclusion in strategy documents and individual management plans. With an emphasis on connectivity. Connecting people to woodlands and connecting woodlands to other woodlands.

- Migrate woodland and other natural environment data to a webmap.

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 1-3. Belfast City Council | TBC - Medium term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| No information about publicly owned natural areas. | Publicly owned natural areas identified in a “natural areas survey” or similar document or on webmap. | Survey document also tracks level and type of public use in publicly owned natural areas. | In addition, usage patterns, ecological structure and function of all publicly owned natural areas are also assessed and documented. |

|

T7 Trees on Private Property

Trees on private property are more difficult to survey and manage than those on public land due to the extent and inaccessibility of these trees. It relies on landowners taking an active role in tree management.

In addition to an i-Tree Eco sample based analysis, a detailed assessment of the Urban Tree Canopy which can be displayed on a city-wide basis should be carried out for optimal results.

A full inventory of trees on private properties may be a tall order, however many of Belfast’s trees will fall into conservation areas, and many more will be on record with a tree preservation order (TPO). Fully collating the data already held on these trees may be useful in combination with an i-Tree Eco sample survey.

Furthermore, the Bluesky National Tree Map (NTM) also provides an estimate of tree numbers and could be used in conjunction with OS mastermap to provide a point based assessment relatively quickly.

Actions

- Ongoing review and update of existing interactive maps for current TPO and Conservation sites.

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 1. Belfast City Council | TBC - Short to Medium term project |

| Current performance level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| No information about privately owned trees. | Aerial, point-based assessment of trees on private property, capturing overall extent and location. | Bottom-up, sample-based assessment of trees on private property, as well as basic aerial view (as described in “Fair” rating). | Bottom-up, sample-based assessment on private property, as well as a detailed Urban Tree Canopy (UTC) analysis of entire urban forest, integrated into municipality-wide GIS system. | |

T8 Other Elements of the Urban Forest - including Biodiversity

Other elements of the urban forest include shrubs, hedges, green walls and roofs, plants, wildlife, and water. These elements, along with trees, provide a wide range of benefits, including ecosystem services and amenity value.

Whilst shrubs, like trees, can be surveyed (for example as in the i-Tree Eco project), and green walls and roofs can be counted and measured, many of these other elements are very difficult to quantify, such as biodiversity for example. Assessing and quantifying these environmental impacts and services is even more complex. However, tools like the Urban Greening Factor (UGF) as used in London can provide a guideline and targets for urban greening.

In order to maintain and enhance the urban forest, Belfast needs to consider these other elements and to identify opportunities around new greening, biodiversity enhancement and development. This will help the city to make the most of its urban forest so that it continues to provide benefits to the community into the future in both a meaningful and quantifiable way.

Vegetation grows on the external facade of the Skainos Centre on the Newtonards Road

Actions

- Information on these elements may be available from other third parties - needs enquiring, collating and reviewing find the gaps.

- Research and review current tools and best practices for measuring and quantifying these additional elements.

- Commit to developing a new biodiversity action plan.

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1-3. Belfast City Council | TBC - Short to Medium term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| No information about other elements of the Urban Forest. | An assessment of existing elements of the urban forest has been carried out and a green infrastructure baseline has been established. | Establish relevant local UFG targets. Identify opportunities for new greening in development. | A relevant local UFG policy has been developed and implemented. Monitoring is ongoing. |

|

T9 Tree Benefits

Trees in cities bring with them both benefits and costs. Whilst many of the costs are well known, the benefits can be difficult to quantify or justify. Nevertheless, a considerable and expanding body of research exists on the benefits that urban trees provide to those who live and work in our cities, to green infrastructure and to the wider urban ecosystem.

Trees provide a ‘sense of place’, moderate extremes of high temperature in urban areas, improve air quality, reduce rainwater runoff, and act as a carbon sink. Yet, trees are often overlooked and undervalued. Understanding and valuing these services allows us to make more informed planting and management decisions for the benefit of current and future generations. It can also help communicate the importance of trees to the public and to those in the planning and development sector, encouraging the protection and management of existing trees as well as new planting.

i-Tree Eco is a tool which can be used to quantify tree benefits whilst also giving an overview of the structure of the urban forest. The random plot sample survey of Belfast provides a comprehensive analyse of the quantifiable tree benefits. Not all benefits are quantifiable, however amenity valuations (i.e. CAVAT) can help with valuing urban forests.

Belfast One Million Trees project conducted an i-Tree Eco valuation of the urban forest in 2022. The results of this study can be found at: https://www.treeconomics.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Belfast-i-Tree-Eco-report.pdf

About i-Tree

i-Tree is a suite of tools developed to assess the value of the urban forest and the ecosystem services provided which:

- Quantifies the benefits and values of trees around the world.

- Aids in tree and forest management and advocacy.

- Shows potential risks to tree and forest health

- Is based on peer-reviewed international research.

i-Tree Eco is an application designed to use field data from individual trees, complete inventories, or randomly allocated plots across the sample area to analyse the forest structure and ecosystem services provided.

Actions

- Resurvey in 10 years.

Relevant corporate policies

- Belfast Open Spaces Strategy

- Belfast Metropolitan Transport Plan

- Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 1. Belfast City Council | 2032 |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| No comprehensive information available about tree benefits in the city. | Some information available on key tree benefits, such as biodiversity. | Sound information available on a key set of tree benefits, such as biodiversity, recreation, environmental services. | Comprehensive information available on all tree benefits across the city. | |

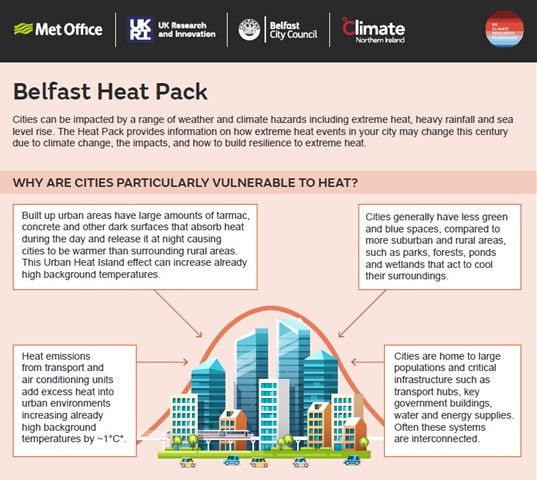

T10 Wider Environmental Considerations

Belfast's urban forest has a vital part in the fight against climate change and can be part of both adaptation and mitigation strategies. Urban trees and woodlands are particularly important as a way of reducing the urban heat island effect, and in removing air pollution from built-up areas and highways. In certain situations, trees can also reduce the energy use of buildings by providing shade in summer (reducing the need for air conditioning) and insulation from cold winds in winter (reducing the heating costs).

With the UK target of carbon net neutrality by 2050, and Belfast's aims to achieve 66 per cent reductions on its 2000 level of emissions by 2025, 80 per cent by 2030, 88 per cent by 2035, 93 per cent by 2040, 97 per cent by 2045 and 100 per cent by 2050, the trees and other elements of the urban forest in Belfast are key.

Climate change poses a direct risk to the residents in Belfast; a warming climate increases risk of heatstroke, while increased rainfall will cause more frequent and more severe flooding. Biodiversity is also at risk, as species will struggle to adapt to warming climates, earlier springs and mild winters.

These considerations should be taken into account when managing the urban forest to ensure that the correct management practices are being enforces, tree and shrub species are as suitable to the future environment as possible, and that biodiversity is protected and enhanced, with biodiversity net gain as a key drive. Monitoring species and numbers will be important, and considering opinions from outside groups regarding more specific systems and locations will be key to preserving existing environments in Belfast. Working with the most up to date and location relevant climate and weather data is important to avoid generalisations and achieve the best results for the future.

Figure 9: Pollution of Particulate Matter <2.5 microns concentration across Belfast (Inset: Canopy Cover by Ward)

Source: UKAIR : Website: https://uk-air.defra.gov.uk/data/laqm-background-maps

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2022.

© OpenStreetMap contributors

Actions

-

Complete an urban forest risk assessment to assess the risk from Flooding, Climate change, Pest and Diseases and others.

Relevant corporate policies

- Belfast Open Spaces Strategy

- Belfast Metropolitan Transport Plan

- Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1. Belfast City Council with support from others | TBC - Medium term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| No consideration/information that relates urban trees to climate change, air quality, water. | Some consideration of environmental aspects in relation to urban trees, e.g. looking at climate change. | Consideration of at least major environmental aspects in relation to urban trees. |

Full consideration of environmental aspects in relation to trees, based on comprehensive, state-of-the-art information. | |

Summary

| Key Performance Indicator | Current Performance Level (Low, Moderate, Good or Optimal) | Priority |

|---|---|---|

| T1 - Relative tree canopy cover | Good | High |

| T2 - Size (Age) diversity | Moderate | Medium |

| T3 - Species diversity | Moderate | High |

| T4 - Species suitability | Moderate | Medium |

| T5 – Publicly owned trees | Good | Low |

| T6 – Publicly owned natural areas | Good | Low |

| T7 – Trees on private property | Good | Low |

| T8 – Other elements of the UF; shrubs, hedges, green walls and roofs, plants, animals and water | Moderate | Medium |

| T9 – Tree benefits (including biodiversity) | Optimal | Low |

| T10 – Wider Environmental Considerations (including Climate Change, Air quality and Water | Moderate | Medium |

Targets, Priorities and Actions

3.2 Community Framework

“It is our collective and individual responsibility to preserve and tend to the environment in which we all live.”

- The Dalai Lama

“Trees are a natural thermo regulator. And a vital component of urban life. They provide a solution to

climate change, have economic, social, environmental and health benefits. They help wildlife and connect

communities.”Belfast Resident and consultation respondent

C1 Governance and Leadership

The aim of this target is to help all municipal departments and agencies within Belfast to communicate and cooperate to advance goals related to urban forest issues and opportunities. Belfast City Council will continue to work with other NGOs and agencies when necessary.

However, building a focussed network of urban forest partners to undertake co-ordinated action in delivery of this strategy would be desirable. The council will aim to work with a number of external partners to manage and maintain the urban forest. This may include, among others, The Woodland Trust, The Conservation Volunteers, Ulster Wildlife Trust, the Belfast Hills Partnership, the National Trust, the Department for Infrastructure (DfI), and the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA).

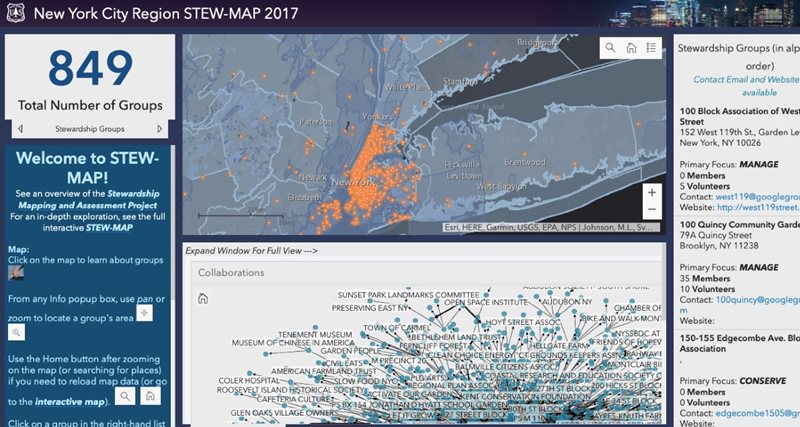

Initially the council will undertake a review of whom the current stakeholders and actors are and where they are working across the city. It will then consider a map tree of stewardship across the city and will canvass opinion on wether to set up a Tree Forum as a means to strengthen and co-ordinate the governance and leadership of the urban forest.

Figure 10: Example Stew Map from New York which details which organisations work in which areas, their size, focus and overlap with others.

Actions

- Conduct a review of potential partners, schemes and community groups.

- Commission a database or stewardship map of Belfast.

- Evaluate setting up a Tree Forum.

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1-3. Belfast City Council | TBC -Medium to Long term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Agencies take actions impacting urban forest with no cross-departmental co-ordination, consultation or consideration of the urban forest resource. Leadership for UF management is fragmented. | BCC works with other NGOs and Agencies on ad-hoc projects as and when they arise. | BCC regularly and frequently works with other NGOs and Agencies to establish projects and plans.There is a cultural champion in place. | Integrated UF governance and leadership provided by a single dept and measured to plan that reflects local and international policies. | |

C2 Belfast Council Departmental Co-operation

This target aims to encourage all departments within BCC to consult and collaborate with the urban forest managers on issues relating to the urban forest. Regular communication across departments and agencies will be key to ensuring that the urban forest is considered to the fullest extent throughout the council. Key departments to incorporate into this network are public health, planning and development. Other key departments include education, housing and highways, which although external to the council, still need to be involved in the process.

Opening communication channels and interdepartmental teams can help to co-ordinate urban forest management by providing knowledge and guidance to all council departments when required in order to ensure that trees and green infrastructure are considered in full at all stages of decision-making.

Belfast Climate Commission and The Resilience Team are good examples of other BCC departments whose own strategies and objectives will overlap with the tree strategy.

Actions

- Set up dedicated interdepartmental/interagency working teams to facilitate the work packages arising from this strategy.

Relevant corporate policies

- Belfast Open Spaces Strategy

- Belfast Metropolitan Transport Plan

- Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 1. Belfast City Council | TBC - Short term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Departments/agencies take actions impacting urban forest with no cross-departmental co-ordination, consultation or consideration of the urban forest resource. | Departments/agencies recognise potential conflicts and reach out to urban forest managers on an ad hoc basis – and vice versa. |

Informal teams among departments and agencies communicate regularly and collaborate on a project-specific basis. | UF policy implemented by formal interdepartmental/interagency working teams on all projects. | |

C3 Utilities Co-operation

C3 aims to ensure that all utilities – above and below ground – employ best management practices and cooperate with the city to advance goals and objectives related to urban forest issues and opportunities. This includes electric, gas, water, cable, telephone, fibre-optics, etc.

Utilities are required to follow certain standards for managing vegetation – including pruning branches, protecting roots, and performing overall management of trees and other vegetation that could impact their services, and city policies may also regulate certain utility management practices, such as overhead line clearance. Introducing and enforcing best practice standards which protect trees and other elements of the urban forest will be key, and collaboration with utilities could help advance the goals and objectives of the strategy.

Some utilities extend beyond the Belfast area. Figure 11 shows the water catchment areas which supply Belfast. These areas are not constrained by political boundaries, and this should be taken into account when assessing how the urban forest and utilities interact. Water companies will also be encouraged to develop systems in which trees provide a vital role in water management.

Figure 11: Hydrology of Belfast shown to extend beyond political boundaries (Inset: Canopy Cover By Ward)

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

© OpenStreetMap contributors

Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2022.

Actions

- Compile list of relevant utility providers and contacts.

- Set up formal initial engagement workshop with utility providers on trees in the built environment.

- Co-ordinate collaborative arrangements to meet the objectives of the plan (e.g. a tree charter that utilities can sign up to when they want to work on BCC land and training courses on trees for relevant employees in these utilities).

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1-3. Belfast City Council | TBC - Short term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Utilities take actions impacting urban forest with no council co-ordination or consideration of the urban forest resource | Utilities employ best management practices, recognise potential municipal conflicts, and reach out to urban forest managers on an ad hoc basis – and vice versa. | Utilities are included in informal council teams that communicate regularly and collaborate on a project-specific basis. | Utilities help advance urban forestry goals and objectives by participating in formal interdepartmental/interagency working teams on all municipal projects. | |

C4 Green Industry Co-operation

The “green industry” encompasses all professions and businesses that routinely support or engage in tree and vegetation management activities. Among others, these can include landscapers, nurseries, garden centres, contractors, maintenance professionals, tree care companies, landscape architects, foresters, planners, and developers.

BCC will work together with green industries to advance municipality-wide urban forest goals and objectives, and adhere to high professional standards. Close co-operation with the green industry presents an excellent opportunity for municipal urban forest managers to influence management of the forest resource on private property.

Actions

- List representatives and contact details for each relevant business or organisation.

- Co-ordinate collaborative arrangements to meet the objectives of the plan (e.g. a tree charter that businesses can sign up to if they want to collaborate with BCC on this plan). This should include discussions on skills building in the sector for Belfast and NI by looking at potential courses and apprenticeship schemes

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate | 1-2. Belfast City Council | TBC - Short term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Little or no cooperation among segments of green industry or awareness of municipality-wide urban forest goals and objectives. | Some cooperation among green industry as well as general awareness and acceptance of municipality-wide goals and objectives | Specific collaborative arrangements across segments of green industry in support of municipality-wide goals and objectives. | Shared vision and goals and extensive committed partnerships in place. Solid adherence to high professional standards. | |

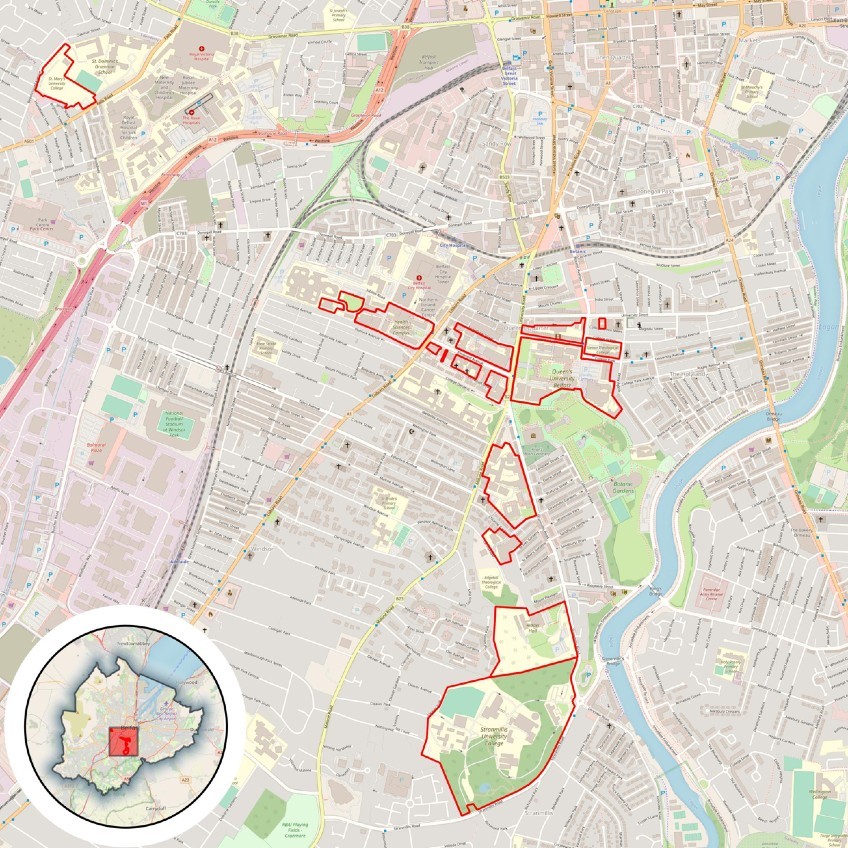

C5 Involvement of Large Private and Institutional Landholders

As a large proportion of land within cities is owned by private individuals, organisations and institutions, enlisting their help in enhancing and protecting the urban forest is paramount. Outreach programs, management plans and funding strategies will help to incorporate these landholders. Communicating the benefits of trees will help inspire landholders and institutions to invest time and money in natural resources.

The goal is to help large private landholders embrace and advance city-wide urban forest goals and objectives by implementing specific resource management plans so that they can manage trees on their property in the most beneficial way.

Belfast's One Million Trees program is an example of an initiative which could be used to guide the development and achievement of this target. The Woodland Trust, Trees for Cities and The Tree Council of Northern Ireland all have good resources on engaging third parties on tree planting and maintenance standards and techniques that can forward this target. There is also more that could be done to collaborate with large institutions, although many already are part of the Belfast One Million Trees Partnership. For example the National Trust, Universities, Belfast Harbour, Crown Estate, DfC, NIHE, Housing Associations, DfI and the Education Authority are all examples of large active organisations in the city centre.

There’s also a suite of supplementary planning guidance for large developers which includes the;

- Planning and Flood Risk SPG,

- Trees and Development SPG and

- Sustainable Urban Drainage SPG.

Figure 12: Map showing Belfast’s Queen’s University Campus and the surrounding green spaces outlined in red

Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2022.

© OpenStreetMap contributors

Actions

- Create database of larger landholders and contact details for each.

- Co-ordinate collaborative arrangements to meet the objectives of the plan.

- Communicating about e.g. health benefits to support partnerships and enhance tree protection.

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1 and 3. Belfast City Council 2. One Million Trees Project |

TBC - Short term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Large private landholders are generally uninformed about urban forest issues and opportunities. | Belfast conducts outreach directly to landholders with educational materials and technical assistance, providing clear goals and incentives for managing their tree resource. | Landholders develop comprehensive tree management plans (including funding strategies) that advance municipality-wide urban forest goals. | As described in “Good” rating, plus active community engagement and access to the property’s forest resource. | |

C6 Community Involvement and Neighbourhood Action

At the neighbourhood level, communities and residents groups will be encouraged to participate and collaborate with BCC and its partnering Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) in urban forest management activities.

Collaborating with smaller community groups such as volunteers, schools and charity groups can encourage further community involvement with projects in small neighbourhoods and wider district areas, which would benefit the whole city. Neighbourhood activities often help the community members to connect more with their urban forest, and encouraging communities to get involved will reduce the likelihood of conflict or opposition to tree planting.

Creating an interactive Stewardship Mapping and Assessment Project (STEW-MAP) such as those completed in Paris and New York may be a useful tool for engaging the public. It is a research methodology, community organising approach and partnership mapping tool developed by the USDA which shows who is responsible for the local environment. It has never been done in the UK and could be an invaluable tool to engage local residents and establish a network of UF management teams across the city.

Introducing a new Tree Warden program for Belfast is potentially a great way to encourage volunteers and community engagement. Belfast will seek to set up a tree wardens scheme over the course of the next 5 years.

Actions

- List reps and contact details for key groups.

- Assess potential for creating stewardship map/mapping of community groups.

- Explore opportunities for a tree equity map.

- Link to other, wider initiatives and awards.

- Publicise events and launches.

- Agree proposals and co-ordinate the planting of living Christmas trees within the city.

Relevant corporate policies

- Belfast Open Spaces Strategy

- Belfast Metropolitan Transport Plan

- Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 1-6. Belfast City Council and NGO could set this up and get funding - done previously by Conservation Volunteers. NGOs will need support for funding though and can't be seen as ‘offloading’ | TBC - Short to Medium term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Little or no citizen involvement or neighbourhood action. | At the neighbourhood level, citizens participate and groups collaborate with Belfast and/or its partnering NGOs in urban forest management activities to advance municipality-wide plans. | Some neighbourhood groups engaged in advancing urban forest goals, but with little or no overall co-ordination with or direction by municipality or its partnering NGOs. | Many active neighbourhood groups engaged across the community, with actions co-ordinated or led by municipality and/or its partnering NGOs. | |

C7 General Appreciation of Trees as a Community Resource

In order for the strategy to be a true success, one of its legacies should be that the people of Belfast love, respect and appreciate its trees. By engaging and encouraging the community in this way, it can be ensured that the urban forest will be protected and enhanced for generations to come. Changing peoples values can be difficult, but through education, celebration and engagement, the hope is that people will come to value the trees around them and the wider part which they play in the health of the city, the nation, and the world.

Not only local communities, but also stakeholders from all sectors and constituencies within the city – private and public, commercial and nonprofit, entrepreneurs and elected officials, community groups and individual citizens – should understand, appreciate, and advocate for the role and importance of the urban forest as a crucial community resource.

“Having public agencies, private landholders, the green industry, and neighbourhood groups all share the same vision of the city’s urban forest is a crucial part of sustainability. This condition is not likely to result from legislation. It will only result from a shared understanding of the urban forest’s value to the community and commitment to dialogue and cooperation among the stakeholders.”

Clark et al., 1997

Figure 13: Tree Tag Examples

Sources and references:

Clark, J.R., Matheny, N.P., Cross, G. And Wake, V. (1997). A Model of Urban Forest Sustainability. Journal of Arboriculture. Volume: 23. Issue: 1

Actions

- Investigate setting up a local tree awards scheme.

- Review methods for gauging and measuring this target.

Relevant corporate policies

- Belfast Open Spaces Strategy

- Belfast Metropolitan Transport Plan

- Belfast Green and Blue Infrastructure Plan

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1-2. Belfast City Council | TBC - Short to Medium term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| General ambivalence or negative attitudes about trees, which are perceived as neutral at best or as the source of problems. Actions harmful to trees may be taken deliberately. | Trees generally recognised as important and beneficial. | Trees widely acknowledged as providing environmental, social, and economic services – resulting in some action or advocacy in support of the urban forest. | Urban forest recognised as vital to thecommunity’s environmental, social, and economic well-being. Widespread public and political support and advocacy for trees, resulting in strong policies and plans that advance the viability and sustainability of the entire urban forest. | |

C8 Regional Collaboration

As a leader in NI green infrastructure and urban forest management it is important that Belfast reaches out to neighbouring towns, cities, and municipalities to encourage collaboration, cooperation and innovation of the urban forests across the region and the country. In supporting its neighbours, Belfast can help provide much-needed guidance and advice by creating a communication network, and in doing so, secure the future of many smaller areas.

The Million Trees Project aims to plant one million native trees across Belfast by 2035. Already, 63,000 trees have been planted in Belfast and the surrounding city regions. This is a vast undertaking which requires regional collaboration and communication to succeed in the given timeframe.

Community initiatives could provide an invaluable opportunity to promote the progress made by the city in terms of urban greening and green infrastructure.

Widely publicising events all year round such as National Tree Week (usually in late November to early December), Arbor Day, planting days (winter time) and outdoor events, will bring focus onto Belfast’s urban forest, and encourage visitors from the surrounding areas.

Belfast supports the creation of nature recovery network in order to reverse the decline of biodiversity and enable nature's recovery at scale. The National Trust, the Woodland Trust, Ulster Wildlife, and RSPB, recently partnered on a project to build capacity to deliver a Nature Recovery Network in Northern Ireland. Belfast's urban forest will have an important role to play in the development of the network creating corridors and joining up habitat for wildlife.

Actions

- Work with BCC Comms team to be made aware of the plan and its ongoing initiatives.

Relevant corporate policies

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 1. Belfast City Council | 5 years |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| Const. and Wards have no interaction with each other or the broader region. No regional planning or co-ordination on urban forestry. | Some neighbouring municipalities and regional agencies share similar policies and plans related to trees and urban forest. | Some urban forest planning and cooperation across municipalities and regional agencies | Widespread regional cooperation resulting in development and implementation of regional urban forest strategy. | |

C9 International Reputation

To bring Belfast to the forefront of urban forestry both in the UK and internationally, it should aim to become a part of international schemes. The Biophilic City Network (https://www.biophiliccities.org/ birmingham-uk) and Tree Cities of the World (https://treecitiesoftheworld.org) are world renowned programs which certify that the city has achieved -and continues to work towards- a diverse and healthy urban forest.

These internationally recognised titles help to promote understanding that the urban forest and the management of it, is of a recognised and high international standard. With the Million Trees Project underway, Belfast’s reputation of being a 'green' city is growing, and the city should aspire to join such initiatives.

Not only will Belfast push to achieve these international initiatives, it shall endeavour to lead by example and provide guidance to other cities worldwide. To succeed in this, Belfast should promote its successes and continue to innovate its forest management strategies and GI development plans.

In will do this by working to this plan, actively promoting itself as a ‘green' city, continuing to learn and engage with new best practices, sharing knowledge and its successes, such as the Million Trees Campaign.

Figure 14: The Dalai Lama planting a tree in Belfast in 2000

Actions

- Research Urban Forest International initiatives, awards and schemes and review which may be suitable for application.

Relevant corporate policies

- 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

- FAO Green Cities Initiative

- UN Habitat - The New Urban Agenda

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Medium | 1. Belfast City Council | TBC - Medium term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| There is no vision - aspiration or consideration of Belfast as an UF of International reputation. | Belfast is sometimes considered for its leadership in international contexts, based on specific efforts and projects | Belfast has signed up to international programs such as Tree cities of the World and the Biophilic City Network and makes good use of these networks to further its UF program. | Belfast is regarded as an international example and leader in its UFM and is prominent on the international stage as a UF city. | |

Summary - Community Framework

| Key Performance Indicator | Current Performance Level (Low, Moderate, Good or Optimal) | Priority |

|---|---|---|

| C1 - Governance and leadership | Moderate | Medium |

| C2 - Belfast Council departmental cooperation | Good | Low |

| C3 - Utilities cooperation | Moderate | Medium |

| C4 - Green industry cooperation | Moderate | Medium |

| C5 - Involvement of large private and institutional landholders | Moderate | Medium |

| C6 - Community involvement and neighbourhood action | Good | Low |

| C7 - General appreciation of trees as a community resource | Moderate | Medium |

| C8 - Regional collaboration | Good | Low |

| C9 - International Reputation | Moderate | Medium |

4. Sustainable Resource Management Approach

“Someone's sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago”

Warren Buffet

“A co ordinated approach with appropriate upkeep would ensure the City will benefit from a healthier and greener environment.”

Belfast Resident and consultation respondent

R1 Tree and Woodlands Inventory

A tree and woodland inventory involves taking stock of the individual trees within the urban forest. It is time and labour intensive to compile a full tree inventory of all trees, and would be unrealistic to achieve. However, plot/sample based inventories of woodland areas, combined with existing street and park tree inventories are a good place to start.

BCC should continue to build upon its existing tree inventory datasets for parks and street trees. It is important to ensure that data is uniform, both in its methods of collection and its format so that it can easily be compared from ward to ward, and over time.

Compiling the inventories of Belfast’s trees into a single portal or system, would be an essential starting point to establish the structure of the urban forest, including the number of trees, diversity of species, and age distribution of council owned trees. This is important as a baseline from which to monitor future progress and from which to manage the tree stock.

Although an i-Tree Eco study has been completed, this gives an overview of the total urban forest both public and private. Though vital, this is not representative of the council managed trees, and therefore decisions on species, health and management may differ. Ideally, in time Belfast will know the complete structure of the urban forest as a whole, and also by ward across the city.

Actions

- Review current Tree Management software and update if required with additional data on Street Trees and Woodlands.

- Investigate wether it will be possible and feasible to include hedges and hedgerows within a tree management system.

Relevant corporate policies

- UK’s Nationally Determined Contribution

- The UK Climate Change Act

- The 25 Year Environmental Plan

- Clean Air Strategy

- Clean Growth Strategy

| Priority | Responsibility for action | For review |

|---|---|---|

| Low | 1. Belfast City Council | TBC - Medium - Long term project |

| Current Performance Level | Performance Indicators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Low | Moderate | Good | Optimal |

| No inventory. | Complete or sample-based inventory of publicly owned trees. | Complete inventory of publicly owned trees and sample-based privately owned trees that is guiding management decisions. | Systematic comprehensive inventory system of entire urban forest – with information tailored to users and supported by mapping in municipality-wide GIS system. | |

R2 Tree Valuation and Asset Management Approach

Tree valuation is an important part of managing and promoting the urban forest. With the trees valued, local people can understand the value of trees beyond the material worth. With these figures to hand, advocating for trees becomes easier.